Can We Solve This?

Examining our approach to crises like hurricanes, mass shootings, and our health with inspiration from lower smoking rates.

Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

September was a devastating month for so many of our friends and neighbors across this country. It started with Hurricane Fiona destroying large parts of Puerto Rico, which had spent the last five years rebuilding from Hurricane Maria. Then last week, Florida and the Carolinas were hit hard by Hurricane Ian.

The damage to homes, businesses, and infrastructure like roads and bridges is unfathomable. People’s lives will be upended for the foreseeable future and it will likely take billions of dollars and years of effort to rebuild.

As I watched the destruction play out across the American South and Puerto Rico, I couldn’t help but feel like I had seen this same scene many times recently.

When I worked at This Old House, we made what the slightly unprecedented decision in 2008 to visit New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and help rebuild parts of the Lower and Upper Ninth Wards. Prior to that series, the only other time the show’s then 30 year history that we had devoted a series to hurricane relief was after Hurricane Andrew destroyed parts of Miami in 1992. Telling the stories of homeowners and neighborhoods devastated by natural disasters wasn’t done much because severe weather events seemed rare.

The series in New Orleans turned out to not be so novel after all. It was closely followed by a series in New Jersey rebuilding after Superstorm Sandy and then one in Paradise, California after the devastating wildfires. If you were telling the stories of homes, it became harder to avoid discussing how nature was threatening them.

When Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria hit parts of the U.S. in 2017, I was in charge of Ask This Old House. We knew that recovering from those storms was on people’s minds, and we thought showing storm cleanup was a new story to tell.

We traveled to Houston and devoted an episode to mold remediation efforts in flooded houses, saw how homes that were too far gone were demolished, and salvaged homes that were able to be saved. We also spotlighted several volunteer groups that were feeding and housing people from around the country who wanted to assist in the rebuilding effort.

The episode was difficult to make emotionally. We were surrounded by so much loss and witnessed lives forever changed by a storm. The episode eventually won a Daytime Emmy Award, but like most media stories around severe weather, the narrative focused on how we rebuild after a catastrophic event rather than investigating the root causes of why an event occurred and if we can reduce our risk in the future.

It’s unclear at this stage how the media will handle the stories of Hurricanes Fiona and Ian. Perhaps as the severity and frequency of storms increase, global warming becomes harder to ignore. Still, the easier stories to tell are the stories about the resilience of the human spirit. We clean up then move on. It is much harder to investigate how humans are contributing to severe weather events and what might be done to prevent them in the future.

I’m not sure if this a human trait in general or more a condition of our modern media environment, but there are plenty of examples of similar situations where we choose to treat the symptoms rather than fix the problem.

For example, mass shootings are a constant threat here in America. They take place in schools, workplaces, shopping malls, movie theaters, supermarkets, at concerts, at and houses of worship.

Nightly news anchors visit the affected town and cover the vigils for the victims. Politicians glibly offer “thoughts and prayers” but treat these shootings as an Act of God that have no possible way of being prevented. We refuse to really examine why mass shootings continue to happen, and without doing that, we have no hope of them ever stopping.

There are many more examples where we choose to only describe a problem rather than investigate the causes. Deaths from car accidents are seen as an unavoidable part of our existence. Housing costs continue to rise and many of our metro areas are now unaffordable to the working class, but the reason why is poorly understood.

11% of the U.S. has diabetes, and 38% of U.S. adults are pre diabetic, with these rates really spiking over the last 20 years. Obesity now affects 41% of the country. We are an unhealthy people, yet the role of highly processed foods from large food companies and poor growing conditions from agribusiness are rarely implicated. Folks like Dr. Oz made a living recommending minor tweaks to diet based on personal responsibility like adding a cup of blueberries or drinking red wine rather than recommending structural changes to our food system. Our health care system does a much better job treating a disease with pharmacological invention than in preventing that disease in the first place.

There is one area that gives me hope that with enough attention and action, we may be able change society for the better: smoking.

It may be hard for younger readers to grasp, but smoking used to be everywhere. In the mid-twentieth century, smoking was associated with the glamor of Hollywood, and news anchors, talk show hosts, and game show panelists were often shown smoking right on the stage. Some of our most beloved classic TV shows, like I Love Lucy and The Flintstones were sponsored by cigarette companies; the stars of these shows filming ads that ran during the commercial breaks.

The peak of smoking in the U.S. was in 1953, when 58% of males and 36% of females were regular smokers. Half of all physicians also smoked at this time. Tobacco companies did an effective job minimizing any risks associated with smoking, using taglines like “gentle on my throat” (Lucky Strike, 1937) and “play safe with your throat” (Philip Morris, 1941).

The Surgeon General first issued a report in 1964 about the dangers of smoking, connecting it to a risk for lung cancer. This was followed in 1971 by a ban against advertising cigarettes on TV and radio.

Despite these efforts, smoking was still ubiquitous during my own childhood in the 1980s and 1990s. Restaurants used to have smoking and non-smoking sections. Sitting in the non-smoking section simply meant not being next to somebody lighting up, though the smell of smoke permeated many restaurants.

We may have not seen Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble puffing Winston cigarettes on TV, but that doesn’t mean we weren't inundated with other tobacco advertising. Cigarette ads appeared as full page spreads in most magazines, and I especially remember the Newport billboards that would line I-90 on the way into Downtown Cleveland. They featured young, vibrant co-eds often engaged in outdoor activities. They were living the good life, while smoking Newports.

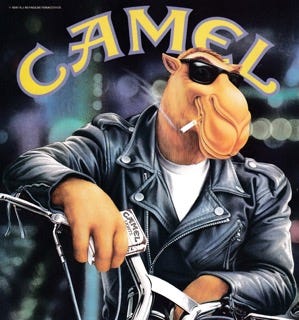

In an era when Saturday morning cartoon characters like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Duck Tales, and Garfield were exploding in popularity, Camel cigarettes introduced a cartoon character to the U.S. market in 1988. His name was Joe Camel, and he was the epitome of cool to a youngster like me. Many of my friends’ parents smoked Camels and they collected “Camel Cash” which could be redeemed for T-shirts and other Camel gear. It wasn’t unusual for a third or fourth grader to wear a Camel shirt to school in the early 90s. Joe Camel was retired in 1997 after complaints to the FTC that the character may have been used to target children.

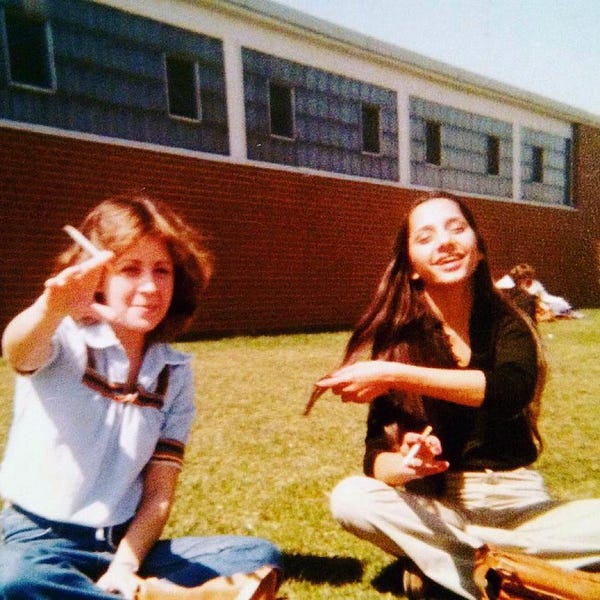

My parents were very clear with my sister and I about the dangers of smoking and they warned us of its addictive nature, but that doesn’t mean our peers didn’t smoke. In fact, this tweet about high school smoking in the 1970s was just as true for me in the late 1990s (except for the heroin part).

The replies in the tweet are very similar to my own experience in middle and high school. We had a bathroom that was unofficially designated as a “smoker’s bathroom.” If a student wanted to smoke during the school day, it was usually overlooked as long as they did it in a particular restroom. The non-smokers knew to avoid that restroom, lest they spend the rest of the day smelling like smoke.

However, even as tobacco companies continued to advertise, the Surgeon General’s warning was always in the background, and a slow but steady public campaign against smoking was starting to take root.

In 1990, a smoking ban went into effect on all domestic U.S. flights less than six hours. This came after banning smoking on shorter flights in the late 1980s. I like how Dave Dobbins, the chief operating officer of the anti-smoking advocacy group Legacy, described the change on airplanes in a Forbes article from a few years ago:

“By the mid-1990s, the airlines came to understand that the vast majority of their passengers liked this change, which was funny because people thought that was impossible – until it happened” Dobbins said. “The majority of people who didn’t have a voice figured out how much better the air quality was when smoking went away.”

In 1998, California took the bold step to ban smoking in bars and restaurants. Other cities and states soon followed suit. Combining these bans with increased taxes on cigarettes, smoking cessation aids like nicotine patches and gums, and a continued public education campaign, an estimated 12.5% of the U.S. adult population smokes today, down from a high of 47% in the 1950s.

These numbers can be deceiving, as there are still pockets of the population with high smoking rates. For those people with only a high school diploma or less, the smoking rate sits at 40%.

Still, through a combination of legal interventions and public education campaigns, the overall smoking rate has been greatly reduced. As a child, somebody could sit next to me with a cigarette and it was so common that I hardly noticed. Now, I may go days without smelling cigarette smoke, and can often detect it from several yards away because it has become so foreign.

Getting back to hurricanes, mass shootings, and the other problems plaguing our country, are there lessons that can be learned from how we addressed smoking?

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act will be a big step in the climate fight. Incentivizing homeowners, landlords, and contractors to consider heat pumps, solar panels, and geothermal can make a massive impact on our greenhouse gas contributions. Encouraging adoption of electric cars, while increasing renewable sources on the grid to power those vehicles, is another important step. Let’s hope the next phase includes additional resources for public transportation, bike lane infrastructure, and development that allows walkability to amenities.

If we can learn anything from the smoking battle, it’s that these problems are not solved overnight. It starts with the knowledge, which in the case of smoking came in 1964 with the Surgeon General’s report. It took some bold action that seemed to be against popular opinion at the time, like banning smoking on planes. This may have seemed controversial and near-impossible, but it made for a better experience for most other airline passengers.

When it comes to climate action, gun control, or the American food system, I see similar forces at work. Industry lobbyists try to convince us that the status quo is working and that there is no need for legislative intervention, but I suspect that once Americans get a taste of less polluting cars, cleaner home energy, or a world with less assault rifles, there will be no turning back.

It has taken 58 years since the Surgeon General’s report to get to this low point in smoking (and there are still communities that are waiting to feel the effects), but it took small steps at every point to turn the tide. I never could have imagined a world without smoking as a child, but it has now become rare and generally socially frowned upon.

Is it possible that my children, born into a world of gun violence and destructive weather events, will look back on this time with the same shock and wonder that I view the Newport ads and Joe Camel swag of my childhood? I hope so.

I was struck by the way that Sarah Kendzior contextualized the future recently. She has been at the forefront of warning Americans how close we are to slipping into an autocracy and was an amazing guest on my podcast back in 2020. In discussing her new book They Knew on Twitter, she pointed out the difference between examining a crisis and giving in to the inevitability of that crisis:

She’s discussing politics here, but I think the lesson holds for this conversation as well. We don’t have to accept a future with continued gun violence or destructive weather any more than we had to accept the tobacco industry’s opinion on smoking. The danger comes in refusing to investigate a situation and take action to solve that problem. As seen with smoking, the solutions may take some time, but every step in the right direction is an important one.

Related Reading

Did I Have West Virginia Wrong?

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Please consider sharing this with a friend that you think might enjoy it, or better yet, share it on social media so you can tell hundreds of friends!

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath

A great take as usual. Unless we take bold actions to deal with societal problems at the source, there absolutely won't be any meaningful change!