Healthy Soil, Healthy People

Exploring how Wendell Berry defines health and practical tips for eating more local foods

Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

My last two Sunday columns were reactions to reading Wendell Berry’s The Unsettling of America, a book first published in 1977 that I find surprisingly relevant today. My first Berry inspired essay was about specialists versus generalists and then I looked at ways we might make our homes more productive.

Practically every paragraph of The Unsettling of America speaks to me in a deep way. It’s been a slower, more focused read for me, as I want to be sure that I am absorbing all of the wisdom contained in the text. It’s not an easy book to skim over or to read in a distracting place, like on a subway or in a waiting room.

I had planned on taking a break from writing about Berry this week, but I am currently reading the chapter titled “The Body and the Earth,” which covers the interconnectedness of the health of our bodies, the health of our souls, and the health of everything around us, including plants, animals, the environment, and the soil. Bodily health and environmental health are two topics that greatly interest me and it was eyeopening to hear how they are connected in Berry’s mind.

Even though I initially thought I had written enough about Wendell Berry, I thought this notion of health merited a bit more exploration. So I hope you will allow me another week of quoting from Berry and connecting some of his ideas to other thinkers that have inspired my concept of health. I also wanted to share some resources that have been helpful to me when thinking about separating from our industrial food system and reconnecting with a more local diet that is focused on healthy air, water, and soil.

Let’s start by looking at why Berry thinks our current definition of health is too narrow:

“That there is some connection between how we feel and what we eat, between our bodies and the earth, is acknowledged when we say that we must ‘eat right to keep fit’ or that we should eat ‘a balanced diet.’ But by health we mean little more than how we feel. We are healthy, we think, if we do not feel any pain or too much pain, and if we are strong enough to do our work. If we become unhealthy, then we go to a doctor who we hope will ‘cure’ us and restore us to health. By health, in other words, we mean merely the absence of disease...

“A medical doctor uninterested in nutrition, in agriculture, in the wholesomeness of mind and spirit is as absurd as a farmer who is uninterested in health. Our fragmentation of this subject cannot be our cure, because it is our disease. The body cannot be whole alone. Persons cannot be whole alone. It is wrong to think that bodily health is compatible with spiritual confusion or cultural disorder, or with polluted air and water or impoverished soil. Intellectually, we know that these patterns of interdependence exist; we understand them better now perhaps than we ever have before; yet modern social and cultural patterns contradict them and make it difficult or impossible to honor them in practice.”

These quotes resonated with me because they echo so much of what I’ve been discovering about health and diet over the last decade or more.

It started with the reading of Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, which first made the connection for me between the health of the land, the health of crops and animals, and the health of our bodies.

After reading Omnivore’s Dilemma and some of Pollan’s other books, my wife and I spent years refining our diet to not only what nourishes our bodies but also that which is healthier for the planet. This started by switching to organic foods. Often, we were still swapping out one highly processed food for another, like switching from Oreo cookies to Newman’s Own Organics Newman-O’s, but it was a start.

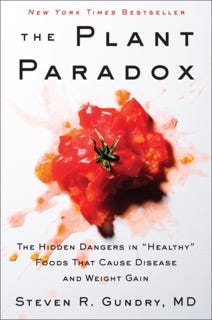

Reading Dr. Steven Gundry’s The Plant Paradox last year helped us recognize that the foods that are considered “healthy” may actually be doing more damage to our bodies. Examples include soy-based products like tofu, whole-grain foods, and nightshade vegetables like tomatoes and eggplant.

Dr. Gundry’s advice is “what you stop eating has far more impact than your health than what you start eating,” and we have eliminated wheat, most sugar, and oils like canola and sunflower oil. The goal is to feed the good microbes in our guts and starve out the bad microbes which make us tired, inflamed, or sick. I hear echoes of Berry in this approach and also in how organic farmers talk about feeding microbes in the soil for healthy crops.

We are approaching our one year anniversary of following Dr. Gundry’s dietary advice and have not looked back. One of the reasons that I became hooked was that this diet fit so nicely with other changes we had been trying to make for years.

For example, Dr. Gundry recommends avoiding fruit unless it is locally picked when in season, which means it is always coming from a local farm. He also advises that meat should be from grass fed cows and pastured chickens. These are harder to buy at a supermarket but abundant at smaller farms.

I interviewed Dr. Gundry on the podcast earlier this year and wrote about the changes in our diet using Dr. Gundry’s findings if you’re interested in learning more.

While Dr. Gundry’s work on the effect of diet on our gut and overall health is largely based on studies from recent years, Wendell Berry noted a general decline in our health 45 years ago and tied it to the health of our land and our farms, writing this in Unsettling:

“And it is clear to anyone who looks carefully at any crowd that we are wasting our bodies exactly as we are wasting our land. Our bodies are fat, weak, joyless, sickly, ugly, the virtual prey of the manufacturers of medicine and cosmetics. Our bodies have become marginal; they are growing useless like our ‘marginal’ land because we have less and less use for them. After the games and idle flourishes of modern youth, we use them only as shipping cartons to transport our brains and our few employable muscles back and forth to work.”

Do you think this statement rings more true in 1977 or 2022? Berry was writing before the advent of genetically modified crops that can be sprayed with herbicides like glyphosate and still survive. In 1977, Coca Cola was flavored with sugar, not high fructose corn syrup. His grocery store aisles may have looked different than ours, but he was already seeing major issues almost a half-century ago.

While my wife and I have been patronizing local farms for years, we really doubled down on this style of eating after reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle soon after starting the Dr. Gundry diet last year. In that book, Kingsolver and her family move to a farm in Virginia and try to eat as locally as possible for an entire year. They raise their own chickens for eggs and meat, grow food crops, forage for mushrooms, and supplement their diet with food grown by neighbors.

Prior to reading Kingsolver, I had been content to shop at local farms during the peak summer months but shifted to shopping at supermarkets in the winter. Kingsolver inspired me to seek out local options year round, and it has been a real game changer for us. I have been amazed how many local food products can be found here in New England, even in the middle of winter, and it has changed how we shop, cook, and eat.

We do still supplement the farm diet with some pantry staples from grocery stores, Costco, and Vitacost, but we have been turning over more of our food dollars to local small businesses.

By combining the Dr. Gundry diet with food from local sources, as inspired by Kingsolver, we have also been giving less of our money to doctors, pharmacies, and pharmaceutical companies.

My wife was able to stop taking a long-term prescription medication after her doctor saw positive bloodwork results from this diet. My seasonal allergies have completely vanished and it’s been almost a year since I last took Claritin, Flonase, or any similar product. I also had persistent headaches that are no longer present and have not had to buy Advil. We’ve also both lost weight that was largely from inflammation and feel so much better.

I have been sharing our journey on my Instagram (and my wife also shares recipes that fit with this diet on her page). We both get questions or comments all the time about how hard it is to eat locally elsewhere in the country.

While it’s true that we are blessed with a bounty of local farms in our area, with a little digging and research, there are farms near all of us that provide healthy meals that nourish us and, as Berry says, nourish the soil.

To take this essay from conceptual to practical, I wanted to share some tips that have worked for us to make us less reliant on a global food system and more reliant on our neighbors. For many of you reading this, the thought of eating locally may be daunting or novel, but I hope what follows may inspire you to seek out more options.

Please feel free to bookmark this page and refer to it again as your journey continues.

Visit Farmers Markets

If you think there are no farms in your area, visit a farmers markets. These can vary widely in size and quality, but they’re almost always worth at least walking through. When you find a good one, you’ll be surprised how many of your staple foods can be purchased there.

The sellers may be the same person that grew the food, but even if they’re not, you can always inquire about growing practices. Sometimes a market may be too busy for small talk with the seller. If that’s the case, I look for a printed map or directory to take home so that I can research the farms that interest me at length later.

Some “farmers markets” are actually made of produce wholesalers, who are selling the same foods that are on supermarket shelves, often grown by large growers out of state or even in other countries. Many large urban markets like Haymarket here in Boston or the West Side Market in my hometown of Cleveland, are dominated by these wholesalers. There can be some savings realized and a slight freshness edge gained, but I prefer to buy directly from a farm.

It’s worth pointing out that most farmers markets these days take credit cards or even touchless payments like Apple Pay. Some markets may even accept food stamps (here in Massachusetts, the Healthy Incentives Program gives recipients extra money on their EBT cards for shopping at farmers markets). For the cashless (like myself), this makes shopping locally much easier.

Visit Farms

In addition to selling at farmers markets, many growers will also offer direct sales to consumers at their farm. If you find a vendor that you like at a market, visiting the farm may be more convenient or may offer greater variety.

My local food journey started with an amazing organic farm that was near my office, Hutchins Farm in Concord, MA. When I first visited there about 10 years ago, it was for an occasional splurge or treat- a fresh pint of blueberries for example. We would still buy most of our food at the grocery store.

Over time, I began to rely on Hutchins Farm more regularly, adding staples like lettuce, onion, garlic, celery, and radishes to my trips. Their prices are competitive with Whole Foods but their quality and freshness is much higher, probably because the food traveled a few hundred feet from the field to the farm stand.

Through Hutchins Farm, I learned about Codman Community Farms, whose farm stand is housed in a beautiful old barn. It is open 24 hours a day, is completely self-serve, and it accepts credit cards. It can be more convenient than a trip to the grocery store!

In addition to raising beef, pork, chicken, and turkeys, Codman Community Farms also sells things like eggs, local cheeses, and mushrooms. It was through Codman that I met Elizabeth Almeida of Fat Moon Mushrooms. She became a friend and was featured in this newsletter earlier this year after she was interviewed for my podcast.

Codman also hosts a pop-up fish market on Saturday mornings with C&C Lobsters and Fish where I buy fresh, locally caught fish.

Had I not ventured into Hutchins Farm more than a decade ago, I may never have discovered the meat and eggs at Codman Community Farms, the mushrooms from Fat Moon Mushrooms, or the fresh fish from C&C Lobster and Fish.

This section has been very specific to my experience, but I hope the general point is clear that local farms can be a network. If you start with just one, it can easily lead to many more, often in unexpected and joyful ways.

Use Social Media

One of the best tools that I have found for researching local farms is social media. Facebook and Instagram tend to be the two most popular platforms for farmers (I am not on Facebook, so my experience in this area only relates to Instagram).

Start by following a local grocer or farm. It’s free! If they have an interesting post where they tag another farm or similar business, give that company a follow too. Some follows may lead to dead ends and that’s okay. You can always unfollow a farm or business that doesn’t resonate with you. But you may discover some businesses that were otherwise not on your radar.

Much like my experience above about visiting farms in person led to more places, that effect is amplified on social media. You can “visit” many area farms without ever having to get in the car.

Many farms are open to DMs as well, where you can ask about growing processes, produce availability, and much more.

Beyond that, social media is often a good place to hear about sales or other events happening at farms or farmers markets. Follow lots of cool local farmers and food producers and you’ll be surprised how much is growing and being made in your area.

Buy Cheap and Store It

It’s worth acknowledging that shopping at a farm can be more expensive than shopping at the grocery store, especially if switching from conventionally grown produce to organic or upgrading to pastured meat. This effect is offset for us by lower costs for medicine and by buying less processed foods, but farms can come with sticker shock at first.

One trick that I have learned to make it more palatable is to take advantage of sales or bulk pricing when it is offered.

One of my favorite deals is buying a “Best of Chicken” box from Lilac Hedge Farm, which offers a savings of almost $30 when buying this 25 pound bundle versus buying each item separately. We invested in a deep freezer a few years ago and store the meat until we need it. Plus, Lilac Hedge delivers it to our door from their farm.

Sometimes if a crop is especially abundant, a farm will offer a discount on large quantities. This is where canning or freezing crops becomes important. I mentioned making sauerkraut last week, and that’s a great way to make use of bulk cabbage. I don’t mind using second quality tomatoes for making tomato sauce or second quality apples for applesauce and they are usually priced much cheaper than their prettier counterparts. Once canned, they will last more than a year.

One last point I want to make on saving money- one of the best things that we’ve ever done is join a CSA, which stands for Community Supported Agriculture. It’s almost like buying stock in a farm. You invest money before the start of the growing season and then receive some portion of the farm’s production each week. In abundant years, there may be bounties of produce (but if there is a drought or an insect problem, the yield may be lower).

We have been members at a few CSAs over the years and find that you really get to know your farmer in a more intimate way. As fall frost looms and the warm season crops are starting to die off, some of our farms have offered unlimited produce if you’re willing to pick it from the fields. This is great for canning or pickling and makes the value received for purchasing the CSA much higher.

We are currently in our fourth year of a CSA with Clark Farm and have been very pleased with what we get from the program. This year, the season began in April and will run through January.

Our diet has been evolving over the last decade and it will continue to adapt. In thinking about Wendell Berry’s take on health, it seems like investing in local farms and buying as little of our food from the big companies is the best thing we can do for our health and the planet’s health.

As Berry points out, these are not discreet ideas but are deeply connected and interwoven ideas.

Related Reading

Getting Acquainted with Wendell Berry

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Please consider sharing this with a friend that you think might enjoy it, or better yet, share it on social media so you can tell hundreds of friends!

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath

Heath, yet another brilliant article. I really need to purchase this Wendell Berry book for myself, as although it was written in '77, it couldn't be any more prescient in its commentaries on various aspects of society. If anything, things have only gotten worse than he could've imagined when he authored that tome.

What I really wanted to discuss, however, is organic food and how much I love it. As a fellow New Englander (I'm originally from South of Boston and today live in Central Vermont), I'm blessed to have so many great local farms from which we can purchase grain-fed meats, produce, and dairy products. In fact, I have really no choice but to acquire mostly organic foods because I have severe food allergies.

My biggest allergies are to whey and soy proteins, meaning that I really can't consume dairy at all; although I can eat eggs without any issue. I actually went completely vegan for several years, but due to soy protein eventually becoming the stock of most processed vegan foods, I decided to nix being fully vegan in exchange for eating eggs, shellfish, and beans as my primary sources of protein. I can't properly digest most meats, especially red meat which actually makes me sick, thanks to having a bout with cancer that destroyed my ability to digest many types of food.

One thing that is a bit disappointing in our neck of the woods in Vermont (yes, literally the woods), is that we live in dairy country. This is great for eggs, obviously, and great for my partner when it comes to milk and cheese. But, when it comes to most organic products, our nearest organic supermarket is in Saratoga Springs, New York, an hour and twenty minute drive one way. Yes, there is one of the same chain in Williston, Vermont, but that's a two-hour drive one way. I lament that our nearest big town, Rutland, has only infrequent farmer's markets and no supermarkets focusing on organic products.

However, now that I'm aware of all these awesome farms in central and western Massachusetts it may be well worth looking into these options, especially as my partner still eats other meat besides the shrimp, scallops, and lobster that I can eat. I'm obsessed with focusing on grain-fed only - as the soy fed to many factory farm animals eventually contaminates everything else. The prices I see are exactly what we pay per pound in Saratoga Springs/Williston, and if we can get greater quantity, something that we've found difficult, that could really be a major benefit to our health!

Again, awesome article, and I look forward to reading many more!