A Tipping Point

If you haven't been giving much thought to fast fashion, maybe a new ad campaign from Zara will change your mind

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscribtion to receive emails every Wednesday and Sunday plus podcast episodes every two weeks. There are also paid options, which unlock even more features.

Zara, the Spanish fast fashion retailer, is once again surrounded in controversy. This time, it’s for the launch of a new ad campaign that has drawn harsh criticism for seeming to take inspiration from the genocide in Gaza. According to one news report:

“Zara said that the central focus of its campaign, titled ‘The Jacket,’ is an exercise in concentrated design that aims to demonstrate the versatility of the garment. However, the promotional pictures have drawn severe criticism for employing unsettling imagery, including what appears to be bodies wrapped in a white body bag reminiscent of traditional Muslim burial attire. The campaign also features rocks, rubble, and a cardboard cutout resembling the map of Palestine.”

In addition to the image above, here are a few of the photos currently posted to Zara’s Instagram profile, which has 61 million followers: (Update: Zara has now pulled this ad campaign).

Having worked in marketing for a few years now, and in television production for many years prior, I can tell you that no detail on a big budget shoot like this goes without scrutiny. Teams spend weeks drawing up concepts, creating sets and props, and editing the final photos before they see release. It’s very unlikely that nobody raised a concern at some point in the creation of this campaign that it could be problematic.

For any art, there’s the content of the work itself and then there’s the context of external factors which may impact how the art is perceived. Even if the content of this ad was settled on and created months ago, it does not excuse that the context of its release changed on October 7.

If I had to hazard a guess, I would say Zara is aware that this campaign will be controversial and is hoping it will get people talking and debating the imagery. I’m writing about it now, and you’re reading about it, so mission accomplished I guess. But they’ve approached this imagery in such a way that they still have plausible deniability, which allows them to benefit from the controversy while still absolving some people’s guilty consciences for shopping at Zara. It’s calculated and frankly sick, considering how many people a day are losing their lives in Gaza.

This one ad campaign might have you rethinking shopping at Zara. But the truth is Zara and similar fashion retailers all have a record that includes accusations of human rights violations and major environmental pollution. If you haven’t considered cutting them out of your life before now, perhaps this will be the catalyst you need.

After reading Amelia Pang’s book Made in China a few years ago and then interviewing her on my podcast, the problems of Uyghur forced labor in Xinjiang (the province in China where most of the forced labor camps are located) really came onto my radar. The Chinese government has been arresting Muslims who belong to the Uyghur minority and forcing them to work in factories without any trial. Many consider the situation by many to be modern day slavery.

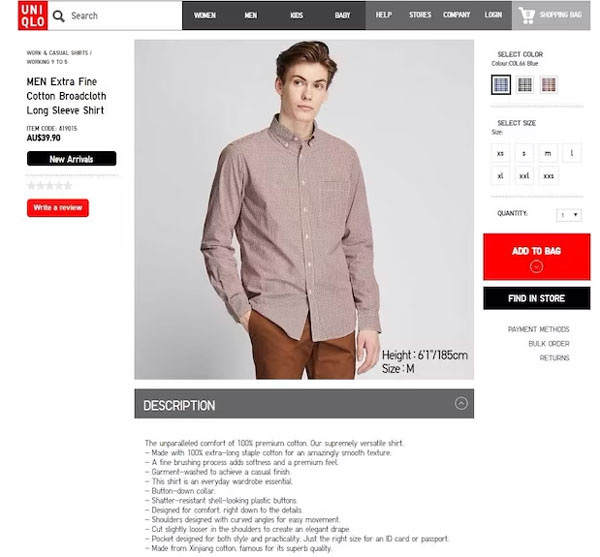

These factories produce garments for many Western fashion brands. Uniqlo once proudly bragged of using Xinjiang cotton, calling it “famous for its superb quality.”

The Guardian published a report just last week drawing ties between suppliers in Xinjiang and major Western brands, including Zara, Primark, and H&M. As Pang pointed out in her book, many of these companies do not directly control their supply chains, instead subcontracting garment production to third parties, who in turn may subcontract that work again.

It’s a form of laundering accountability for the sourcing of goods. H&M or Zara may buy from a more reputable producer, but that company has outsourced production to a company that is using Uyghur forced labor.

Overlooking the labor issues for a moment, there’s also a huge environmental cost to fast fashion brands like Zara. Each year, the fashion industry produces about 100 billion items, double the amount from the year 2000. Zara produces 20,000 new styles every year, while Shein produces 6,000 per day.

The overproduction and overconsumption of fast fashion leads to incredible waste. Unsold inventory is often destroyed without ever being worn even once. Returns, a major problem with online shopping, are also sometimes destroyed without ever being restocked.

Consumers who engage in the unending treadmill of purchasing inexpensive, short term trends that they only wear a few times are a part of the problem too. The average American discards 81.5 pounds of clothing per year.

Clothing is also increasingly made with more synthetic materials, which are essentially created from oil. Cotton or wool are regenerative, in that we can always grow more cotton or raise more sheep. But synthetic fibers like polyester and acrylic are extractive; once we pull oil out of the earth to make plastic clothes, there isn’t a way to create more oil.

These synthetic fibers are polluting our waterways and ultimately poisoning us. According to the UN:

“About 60 per cent of material made into clothing is plastic, which includes polyester, acrylic and nylon textiles. These synthetic fabrics are lightweight, durable, affordable and flexible. But here’s the catch: every time they're washed, they shed tiny plastic fibres called microfibres, a form of microplastics—tiny pieces up to five millimetres in size.

Laundry alone causes around half a million tonnes of plastic microfibres to be released into the ocean every year—the equivalent of almost three billion polyester shirts. This happens because water treatment plants let up to 40 per cent of microfibres they receive into lakes, rivers and the ocean due to their small size. Most treatment plants are not mandated to capture microfibres.”

And of course, there’s the tremendous amount of fuel used to transport raw goods to China for manufacturing, then to transport finished garments around the world for sale.

I’m not suggesting that we give up on clothing entirely. Living in Massachusetts with its cold winters, I’m not eager to be a nudist myself. Fashion is one way that we express ourselves and broadcast something about our personality to the outside world and there is value in that.

I encourage you to consider what it would look like to opt out of a system that is built on slave labor, plastic consumption, and controversial ad campaigns in your own life. Everybody will have a different approach to this.

For me, it has started with buying way, way less. If you’ve been a longtime reader, you know that I’ve now gone more than a year without buying any new clothes. I had lots of clothing in my closet that I didn’t wear and have found that “shopping in my closet” has been quite fun and surprising.

Prior to learning about all of the issues in the fashion industry, I was a big fan of Uniqlo’s minimalist designs and own several shirts from the company. I wouldn’t purchase them again, knowing what I do about their business practices, but I don’t need to discard what I already own in protest either. I plan to hold on to most of my clothing for as long as possible, even if the clothes I currently wear aren’t what I would choose to buy in this moment.

The few clothes that I have purchased over the last year have been second hand clothes from thrift stores. I have bought a few vintage Sears shirts from the 1970s, but also some more modern clothes that I can wear and look fully modern.

If I can’t make do with what I already have and cannot find an item second hand, my last resort is to buy new. When I do, I try to do my homework and find items that are made using better materials and better practices.

I also have tried to opt out of the endless cycle of what’s in fashion at any given moment, instead focusing on what’s durable and versatile. I try to find clothes that I am comfortable wearing to lounge around the house, work in my workshop, to wear to an important meeting, or to an evening performance. This generally means avoiding T shirts with brand names, characters, or other large icons, and instead choosing items that are simpler and that look good.

In my own experience, I’ve found that the less I’m concerned with what’s on display in mall store windows or what celebrities are wearing in gossip magazines, the more I realize that the entire fashion industry was built on marketing messages designed to make us all buy way, way more than we needed.

My own actions of purchasing less may not have made any dent in the sales of Zara, Uniqlo, or H&M, but if enough of us demand better by simply not buying, hopefully some things will start to change.

Whether you’re a clothes hoarder who shops multiple times per week, a heavy thrifter who’s always hunting for a bargain, or a clothes miser who stopped buying new clothes years ago, I would love to hear from you in the comments. How do you feel about fashion today? What role do you play in the consumption cycle? What role would you rather play? Leave your thoughts below and let’s have a conversation!

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Yeah...Sigh. I’m taking this one step further and I’ve suspended most of my yarn purchases, because it’s an issue at those box stores too. I’m supporting smaller businesses, going to the creative reuse more and planning my projects to wear as long as I can fit in them.

People throw away 81 pounds of clothing per year? What? What are they wearing? Where is the money coming from, for these constant shoppers? I have lost a lot of weight this year, and I resisted buying new (thrifted) jeans until I literally could not stand up without the ones I already owned falling off, because...money. My husband and I both need new work clothes - particular professional garments that are only made by a few companies. The bare minimum we will be able to purchase them for is $50/shirt, and his will be more like $70 each, when all is said and done. I keep putting off the purchases, because who has that kind of money?