Aesop and the Four Agreements

How all of our stories connect back to some simple universal truths

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscribtion to receive emails every Wednesday and Sunday plus podcast episodes every two weeks. There are also paid options, which unlock even more features.

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

I still have a strong memory of the first “real” book that I read in school. It was early in first grade and every student was given a paperback copy of Aesop’s Fables.

Up until that point, I had been reading “kid books” like the hardcover Dr. Seuss stories or the flimsy paperbacks by Mercer Mayer or Stan and Jan Berenstain. But suddenly I had a book that looked like what the older kids were reading.

I don’t remember many of the stories well, but I do remember that each one had an explicit moral at the end of it, a one sentence summation that was meant to be a life lesson.

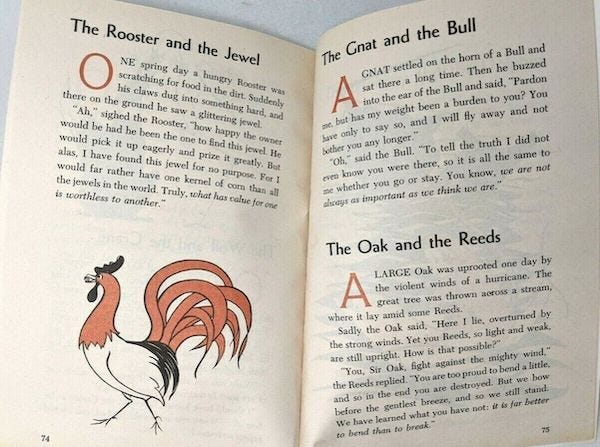

I recently located the exact book that I remember reading on eBay. Looking at photos, I was reminded that the moral was always the last line of the story, written in italics to ensure that the lesson was made explicit:

“What has value for one is worthless to another.”

“We are not always as important as we think we are.”

“It is far better to bend than to break."

The notion of a story with a lesson always stuck with me, although the specific morals were quickly lost. Like any idiomatic phrase, they had a nice sing-song structure that both made them memorable to say and completely forgettable to apply to life.

At the height of the pandemic in 2020, I was once again reintroduced to Aesop’s Fables, although this time, it was a different interpretation.

Being out of work at the time and not feeling great about our kids returning to in person learning, my wife and I decided that I should try homeschooling our daughter for her second grade year. We ordered a curriculum through Live Education, which provides homeschool lessons based on Waldorf education.

For those unfamiliar, Waldorf is an educational movement founded by Rudolf Steiner that came out of Germany in the early 20th century. Waldorf education has a lot of attributes that have always resonated with our family. My wife spent half of her school years in Waldorf schools and forged lasting friendships and a lifelong love of learning that was missing from my public school education.

However, like many things coming out of Germany in the early 20th century, Waldorf and especially Rudolf Steiner also had problematic roots in the racist and eugenicist practices of that time and place. Waldorf schools continue to this day around the world, with many explicitly denouncing the racist tendencies of its founder.

I was drawn to the education system because of its focus on practical arts including woodworking, painting, and cooking. Many Waldorf schools are affiliated with organic farms, as Steiner also defined biodynamic farming, which became the precursor to the organic movement.

In the younger years, Waldorf emphasizes oral storytelling over reading textbooks, so much of my time as a second grade homeschool teacher was spent memorizing stories and reciting them back to my daughter. The first unit in the homeschool curriculum happened to focus on Aesop and his fables.

My younger son is now the age that my daughter was when I homeschooled her. Despite him not attending a Waldorf school, my wife and I thought that introducing him to oral storytelling would be worthwhile. So I recently went back to the curriculum books that I used with my daughter and started supplementing his education with a “lite” homeschool experience that we euphemistically refer to as “Dad Story time” so it feels less like school.

Rather than simply tell the stories with the morals attached to them the way that I learned them in school, the Live Education curriculum encourages the teacher to restrain from explicitly sharing the moral, at least at first. Bruce Bischof, who authored this particular curriculum, explains it thus:

“If we tell the fable or story to the student and allow the image to stand without following it with an explanation, then it lives with mobility within the child's being, it's not fixed to the application and definition given. Also, once an explanation has been given, the story is finished. ‘Oh so that's what it's about,’ she says, and the enigma, the mystery of the story which impels our wonder, is suddenly filed away in the unconscious and dispensed with. Whereas, when the image stands in the mind unexplained, it has the potential to be applied to many instances in life that will be encountered at every age.”

Bischof also explains that after orally presenting a fable, the story should not be discussed or picked apart until the following day. This gives the child time to absorb the story while sleeping.

I’ve been amazed to see this method work with both of my children. I sometimes question as I’m telling a story if they’re even fully engaged, yet the next morning, they have both surprisingly retained even small details about each story and are eager to discuss it. In an era of short attention spans, this is a welcome change to see.

As part of that following day’s discussion, I ask my son to come up with what he thinks the moral or lesson of each story is. I’ve found that my son’s versions of these lessons often fall into very simplistic and nearly universal truths about how to live a moral life. In fact, nearly all of the morals that he pulls out of Aesop seem to follow the ancient Toltec “four agreements.”

For those unfamiliar, The Four Agreements is a popular book written by Don Miguel Ruiz in 1997 which presents four simple rules for living that can prevent unnecessary suffering and lead to true happiness and kindness. They are based on the principles of the Toltec, who originally lived in what is now southern Mexico.

In Ruiz’s version, the four agreements are as follows:

Be impeccable with your word.

Don’t take anything personally.

Don't make assumptions.

Always do your best.

My wife found the four agreements years ago and encouraged me to read about them. I’ll be honest, the first time that I read Ruiz’s book, I was skeptical. It took time passing and another reading of the book for me to really internalize what he was saying and why it was important.

After that second reading roughly a year ago, I have tried to implement these principles into my daily life, going so far as to use an image of them as the lock screen on my phone so that I have a constant reminder of their power. Hearing my son essentially come up with paraphrased versions of the four agreements as the morals he takes from Aesop leads me to believe there’s a greater truth in these words than I initially thought.

I will concisely try to summarize the four agreements, but if this is at all of interest, I highly recommend reading the full book, as Ruiz explains it far better than I can in the space allotted here.

The first agreement, be impeccable with your word, means to understand the power of the words that you use. These are the words that you say aloud to others and also the words that you speak in your own mind about yourself and the world around you.

According to Ruiz:

“The word is the most powerful tool you have as a human; it is the tool of magic. But like a sword with two edges, your word can create the most beautiful dream, or your word can destroy everything around you. One edge is the misuse of the word, which creates a living hell. The other edge is the impeccability of the word, which will only create beauty, love, and heaven on earth.”

Reading that really caused me to reckon with the ways that my own words have harmed others in the past and made me vow to do better going forward. My interpretation of being impeccable means thinking before speaking, not lying, refraining from gossip, and honoring promises.

In Aesop, the lesson of being impeccable with your word comes up several times. The wolf who dresses as a sheep is lying about who he really is to try to score some mutton. In a similar story, a donkey finds a lion skin and dresses in it, scaring all the other animals away. That is until he comes upon a fox and brays, thus giving himself away.

The second agreement, don’t take anything personally, has two meanings. On the one hand, don't allow the negative words of others to bother you, as what they say to you is more a reflection on them than on you. But conversely, don’t allow the positive praise of others to go to your head either.

In one Aesop story, a crow steals a piece of meat out of a cottage window and flies up onto a tree branch to eat it. A fox wanders by, smells the meat, and begins to compliment the crow. He tells her that she has beautiful feathers and longs to hear if her voice is as lovely. The crow is flattered, opens her beak to speak, and drops the meat. It was quickly scooped up by the fox, who wanders off eating it.

The third agreement is don’t make assumptions. According to Ruiz:

“We have the tendency to make assumptions about everything. The problem with making assumptions is that we believe they are the truth. We could swear they are real. We make assumptions about what others are doing or thinking - we take it personally - then we blame them and react by sending emotional poison with our word. That is why whenever we make assumptions, we're asking for problems. We make an assumption, we misunderstand, we take it personally, and we end up creating a whole big drama for nothing.”

Perhaps the most obvious assumption in Aesop is that of the hare who races the tortoise. The hare assumes that he will be the victor by a wide margin, and so he abandons the race course and naps under a tree.

In another story, a fox and stork sit down to dinner. The fox serves soup in a shallow bowl, which the stork’s beak cannot fit into. When the stork returns the favor and invites the fox for dinner, it is served in a vase with a long neck. The stork’s long beak can easily reach inside while the fox’s stout nose cannot. By making assumptions about what works best for our friends without asking their preferences, we cause unnecessary suffering.

The last agreement is always do your best. The truth is, your best varies all the time. Your best on a busy day where you have several meetings and very little time to focus will look different than during a quiet day when you’ve had plenty of sleep and enough time to complete tasks.

Getting back to the tortoise and the hare, the hare did not do his best and thus lost the race. Even though the tortoise was believed to not have a chance, he did his best and ended up winning.

I grew up in a Catholic household, learning the Ten Commandments as the rules to live by. They provide a moral framework, but I also found them a bit confusing and at times oddly specific. For example, was there really a need for 1/5 of the commandments to deal with some version of adultery? Both the adultery ones and the not stealing or lying commandments can all be summed up with the first agreement: be impeccable with your word.

The simplicity of the four agreements is what attracts me to them. As I have begun to take them more seriously and apply them to my life, I have found that these simple agreements are surprisingly universal to nearly any situation.

They also are at the root of moral tales such as Aesop’s fables, which have been handed down orally for a few thousand years. Perhaps that hints more at how our core beliefs as humans are surprisingly consistent, even as religious or ethical customs vary from culture to culture.

If you’re looking to learn more about the four agreements, I again recommend reading Don Miguel Ruiz’s book and seeing how it can apply to your life.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

Getting Acquainted with Wendell Berry

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.