Annie, Woolworth's, and a Racist President

How a simple spell check can open a whole new world of knowledge

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you like what you’re reading, you can sign up for a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox every Wednesday and Sunday and get my latest podcast episodes:

One of the more remarkable things about the internet is how one simple Google search can begin a chain reaction of knowledge, where one disparate concept leads to a whole thread about something unrelated, which leads to another unexpected idea, and so on and so on.

Today’s essay is based on a simple Google search about Aileen Quinn, the young actor who played the titular role of Annie in the 1982 film. It ended up teaching me about filming on location, the history of retail, and a super racist U.S. President. Let me explain.

This all started with last week’s Wednesday Walk, where I shared an image from the 1982 Sears Wishbook of a bedroom decked out in everything Annie, one of nine pages from that year’s catalog which featured merchandise from the movie.

I wanted to confirm the spelling of Aileen Quinn’s name and found myself reading her Wikipedia page. I generally don’t like to rely on Wikipedia as a primary source since people can just make things up and post it, but if something requires further reading, there are usually citations with links to actual articles.

I used to watch Annie a fair amount as a kid. Like most of our movies, it was taped off of TV, meaning it had also been edited down for broadcast. I was much, much older before I ever heard the songs “Let’s Go to the Movies,” “We’ve Got Annie,” or “Little Girls.” The film was also my first introduction to Carol Burnett and Tim Curry. Even having watched the film so much, there were so many gems waiting to be uncovered about it for me.

Quinn came from a show business family. She grew up in Pennsylvania and New Jersey and began acting in commercials in New York as a young girl. She eventually landed a role as an understudy in the Broadway production of Annie before being cast as the lead in the John Huston film.

Later in life, she performed in a band (Ailenn Quinn and the Leapin’ Lizards). From sampling their music a bit on Spotify, it seems to be an eclectic mix of swing music with some rock and country undertones. Even though I like to avoid conflating a character with the actor who played the role, but I couldn’t help but think that this early 1950s sound might be exactly the type of music that Annie (who was 10 years old in the 1930s) might go on to rock as an adult.

Aileen also had a stint as a college professor, teaching in the music and theatre department at Monmouth University in New Jersey.

But her time as a professor wasn’t her first time at Monmouth. I read that the college had been one of the locations used in the filming of Annie, although I didn’t recall a scene that was obviously on a campus.

I did some digging, and it turns out that the building which today is known as The Great Hall had served as both the interior and exterior of Daddy Warbucks’s mansion.

The scenes in that mansion had always stood out to me as a kid. The grand staircase, the three-story foyer, the stained glass skylights- it all felt too beautiful and the scale too vast to have been built on a soundstage. Even in the era before computer generated set extensions, filmmakers used tricks like forced perspective or matte paintings to expand a set or make it look bigger than it really was, but there didn’t seem to be any signs of that in Annie (and yes, as a kid, I was already studying films at that level, even if subconsciously). It turned out that the mansion was real!

The Great Hall actually predates the founding of the college by a few years. Monmouth University was founded in 1933 as Monmouth Junior College. It later became Monmouth College and is today known as Monmouth University. There is also an unaffiliated Monmouth College in Illinois.

According to Asbury Park Press, The Great Hall was built as the private home of Hubert Templeton Parson, president of the F.W. Woolworth Co. in 1929.

Younger readers may not recognize the name, but Woolworth’s was once a juggernaut in the world of retailing. The company started with a single store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in the late 1879. It served the function of earlier general stores while also being the forerunner to dollar stores. The stores were known as “Five and Dimes” or “Five and Tens” because in the early years, every item was either a nickel or a dime (by the 1930s, this policy was dropped in favor of a focus on more general merchandise at all price points).

Forbes provides a sense of the scale of Woolworth’s reach by the early twentieth century:

“By 1927, the company operated over 1800 stores throughout the United States, Canada, Britain, Ireland, Cuba, and Germany. British Woolworth’s were known as ‘three-and-sixpense’ stores while German locations featured a ‘25-&-50 phenning’ pricing structure.”

When I wrote about my visit to Laconia, NH last year, I mentioned that their Main Street once included both an F.W. Woolworth’s and a J.J. Newberry, a competitor that opened in 1911.

My mom remembers shopping at the Woolworth’s that was once a fixture on the main street of Willoughby, Ohio (which is called Erie Street). According to news clippings from the time, when the store opened in 1930, Willoughby was the smallest municipality in the chain’s roster. All Woolworth’s locations in the U.S. closed by 1997, but the stores still survive in many other countries including Mexico.

It’s wild to think that a chain where transactions were made in nickels and dimes could accumulate enough wealth for its president to build a mansion that cost $10.5 million to construct in 1929, but I suppose every business is a bit of a pyramid scheme at its core. The building was made out of the same Indiana limestone that was used on the Empire State Building, plus fifty types of Italian marble. It was designed by architect Horace Trumbauer and his assistant Julian Abele, who was believed to be the first African American professional architect.

The mansion actually sits on the site of a former home built for the president of New York Life Insurance Company in 1903 which was destroyed by fire in 1927. In 1916, the mansion, then under the ownership of the head of the Siegel-Cooper department store, was loaned to the presidential campaign of Woodrow Wilson, who used the mansion from September 1 to November 8.

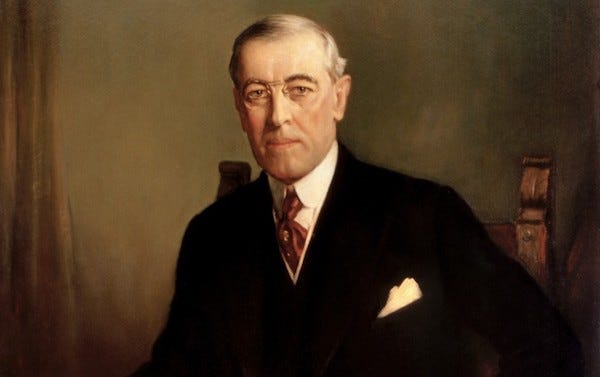

Even though Wilson didn’t campaign in the current structure and only spent a few months on the grounds, the building was nonetheless named Wilson Hall in honor of the former President. It was renamed “The Great Hall” in 2020 when many organizations took a closer look at names and statues that honored people with racist legacies.

I didn’t know much about President Wilson, but it turns out that he was pretty blatantly racist. How racist? Well, the web site for the home where he lived in Washington DC after leaving the White House (which now serves at the Wilson House Museum) includes an entire page discussing his legacy on race.

Wilson was born in Virginia and raised in Georgia and South Carolina during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. He later settled in New Jersey, becoming a professor at Princeton and later the governor of the state.

He is considered a Progressive for a number of governmental and social reforms that happened during his term, including the passage of women’s suffrage and the federal prohibition on alcohol. He established the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations, for which he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. He also appointed Justice Louis Brandies to the Supreme Court, the first Jewish person to hold that position.

Yet Wilson also carried the perspective of his Southern childhood with him to the Presidency and is considered the first Southerner elected to the presidency since the Civil War, despite spending much of his adulthood in New Jersey. The federal government had been desegregated during Reconstruction, which allowed an avenue for the professional advancement of Black Americans. Wilson reversed that, permitting his secretaries to institute segregation within their departments under the guise of promoting “efficiency.”

Wilson screened D.W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation at the White House, which glorifies the Ku Klux Klan as redeemers of the Reconstruction era. According to the Wilson House account:

“After the screening, Wilson was quoted as having declared that the film was ‘like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.’ As a Ph.D. historian himself, Wilson’s words lent credence to this racist, false understanding of American history.”

Wilson’s era was also one where Congress sought to limit immigration to the U.S. While Wilson vetoed several bills that would cap immigration or require literacy tests for immigrants, his vetoes were more on technical grounds. Wilson supported several parts of the laws which would ultimately get passed, including limiting immigration from all Asian countries except the Philippines.

In learning more about Wilson’s racist policies (thanks to learning about filming locations for Annie), it brings about an interesting reminder about U.S presidents, history, and the story that we tell ourselves.

My family and I are headed to Disney World for a few days and I’ve been thinking about the Hall of Presidents show, where audio animatronic figures of every president appear on stage and a few of them give short speeches.

The show is housed in a grand building which resembles Independence Hall. It includes a patriotic film before the presidential figures are presented and the overall vibe is generally positive. In recent years, people have taken to cheering or booing when certain contemporary presidents are presented, but for the most part, the impression the show tries to make is that these white men (save for Barack Obama, the only face of color in the crowd) are heroes.

At this point, I mostly know the names of these men from seeing them on the walls of history classrooms. How many other Woodrow Wilsons are out there, who are glorified for one part of their legacy but also have a terrible record on race, gender, or other issues? What do I really know about Franklin Pierce, Martin Van Buren, or John Quincy Adams? Not much at all.

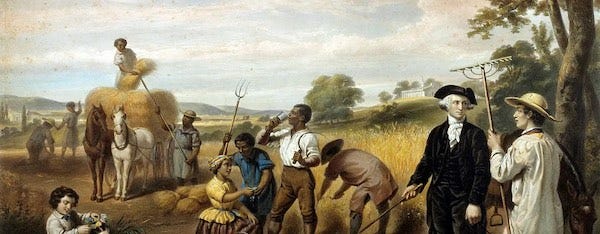

I only recently learned from a book that I picked up at my library’s book sale that George Washington isn’t just the general that won the Revolutionary War, isn’t just the guy on our money, isn’t just that who crossed a river once. He was also a slave owner and likely a slave breeder too. Yikes!

I think for me, there are two takeaways here. The first is that learning doesn’t stop when you leave school. Many of these lessons were never taught in any way during all of my years of education. Whether that’s a case of an individual teacher’s bias, the bias of the entire curriculum, that there’s too much to try to cram into an eighth grade history class, or most likely some combination of all of that, the result is that I didn’t learn everything I needed to in school and the process of learning is lifelong.

The other takeaway is that learning can happen anywhere if we are open to it. I didn’t set out to try to uncover the racist legacy of an early twentieth century president. I was simply trying to make sure that I spelled a child actor from the eighties name correctly. And look where it led.

As you go about your day, be open to learning and be ready to let go of your old notions of things when new information is presented. That’s the only way for true knowledge to take root.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

At the Corner of Washington and Summer

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.