Artistry vs Craft

How our expectations around food, music, and woodworking have reshaped what it means to be good at something

Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

I mentioned a few weeks ago when writing about Howard Johnson’s that I was reading Ten Restaurants That Changed America by Paul Freedman. I finally finished the book last week and was surprised how the ending reframed my thinking about art.

The book is a deep dive into American culinary history, looking at both fine dining trends and more pedestrian fare that had a big impact. One clear theme throughout the book was the outsized influence of the French on how we traditionally ate in the U.S, particularly in cuisine, kitchen hierarchy, and restaurant style.

This trend has abated over the last half century or so, with flavors and traditions from other parts of the world appearing more. The farm to table movement has also brought a rustic and casual feel to American restaurants, often taking cues from Italy and the Mediterranean more than France.

Many of the restaurants that Freedman profiled from earlier times had similar traditional menu items, which again, were largely French in origin. These days, there is less desire for a familiar dish done “properly” and more for surprise combinations, experimentation, and originality.

The celebrity chef is the centerpiece of a restaurant, supplanting the front of house staff as the focus. Open kitchens and chef’s tables are a part of that trend.

Quoting from Freedman about the changes over the last 30 or so years:

“In the foreword to Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Julia Child observed that the Frenchman looks for a ‘well-known dish impeccably cooked and served.’ Even in France this is no longer the rule and certainly in the United States has a quaint, archaic feel. The downfall of French authority and the rise of the creative chef have meant an impetus in the direction of ‘endless reinvention,’ in the words of Daniel Humm, chef of New York's Eleven Madison Park. For better or worse (and there is a downside), the top chefs are no longer masters of a craft but artists.”

There are still some restaurants that serve familiar and formulaic dishes. Diners, for example, will often have similar menus with understood norms. A reuben sandwich will always be a corned beef on rye bread in a certain style of restaurant.

But when I dine out elsewhere, I may want (or even expect) a riff on that comfort food. Legal Sea Foods here in Boston serves a salmon reuben, which borrows elements of the classic sandwich, but subs out the beef for fish. I’ve also eaten a reuben pizza before, which smeared corned beef, sauerkraut, and Russian dressing on a crust and baked it.

Burgers or pizza in a nice restaurant have no standard and often serves as a blank canvas where a chef may show his or her creativity. The same goes for noodle dishes, rice bowls, and even humble salads.

As a home cook, I respond to the improvisational approach of Jamie Oliver, the British chef who encourages using what you have on hand and what is fresh versus needing a specific ingredient. He can explain how changing his recipes may affect the finished dish, but he allows the home cook to experiment.

Contrast that with some other cooking shows or modes of teaching, that emphasize one “correct” ingredient list and technique. If you don’t have that specific frying pan or rubber spatula, good luck to you. Jamie Oliver’s approach is more that of an artist, while the other ways teach mastering a craft.

Craft and art both evoke hand crafts like woodworking to me. I know from my time at This Old House that there can be a big difference between a master of a craft and an artist.

I think of craft as what is taught in the pages of Fine Woodworking magazine. There is an agreed upon way to build a Shaker table, for example. The beauty is in mastering the details perfectly, learning to work your saws and chisels in such a focused and perfect way that the work almost becomes invisible.

I always had a hard time with the craft side of woodworking myself. That’s not to say that I don’t appreciate fine carpentry done by a practiced hand, but I found that approach to be rigid and inaccessible as a novice trying to get into the game.

What drew me to woodworking and other building projects was meeting Jimmy DiResta years ago and producing a number of TV segments with him. (I’ve also interviewed him twice on the podcast (in 2020 and 2022) and wrote about him in the newsletter a few months ago.)

Jimmy is an artist. That’s not to say that he can’t make fine furniture, it’s just that he does improvisational building so much better.

For me, it was sometimes hard to pin down Jimmy’s exact approach to a project when we would talk during preproduction because This Old House tends more towards the school of craft. I would call him ask what type of wood he’d want to use and offer to help source it for him. Jimmy would respond with “I have some wood here” but wouldn’t specify what it was or how he planned to use it.

I wouldn’t learn until the shoot that Jimmy had a massive wood pile and could literally make anything work for us, whether it was using a beautiful slab of oak or maple from a local sawmill or scraps of pine leftover from another project.

One time, we built a table that was going to have painted legs. I asked Jimmy if he wanted me to buy paint and in what color. He reassured me that he had paint. When we got there with the cameras, he took out 3 cans of half-used paint and eyeballed a mixture until he got to his desired hue of a dark green. A craftsperson would insist on a specific shade of Benjamin Moore in a particular sheen; an artist can roll with the punches and can mix up something equally effective on the fly.

After working with Jimmy, I felt more confident to tackle my own woodworking projects. I had always been afraid to try because I was surrounded by such masters of their craft and felt like if I didn’t understand the difference between a rabbet and a dado, I was doing it wrong.

Jimmy taught me that it didn’t matter if I knew the term (or even the “right” way to make one). The importance was understanding the why and how things went together, and there are several approaches to making the same cut that are all equally valid.

Nick Offerman takes a happy medium approach with his woodworking book Good Clean Fun. He celebrates the craft, but also teaches novices like myself how to get involved without being intimidated by expensive tools or specific terminology. Reading this book was another important step in building my confidence.

This craft vs art approach also comes up in the performing arts like music.

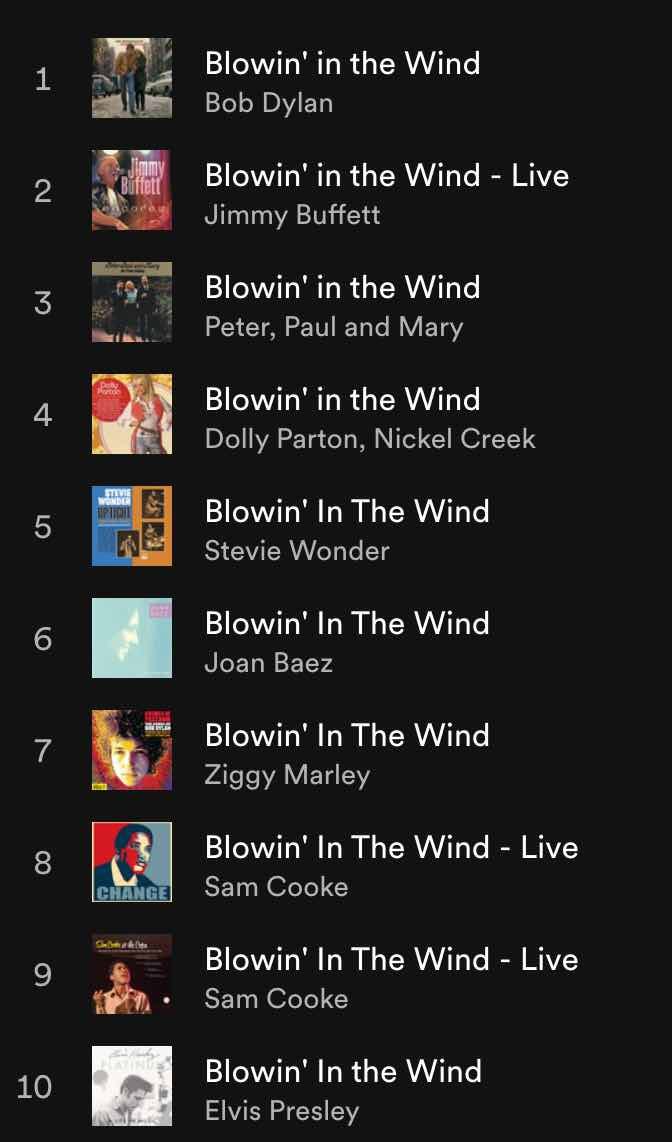

On our recent RV trip, I was listening to Pandora, when a familiar song played. I forget exactly which song it was, but for the sake or argument, let’s call it Blowin’ In The Wind. It dawned on me on that many of those folk songs from the 1960s are hard to trace back to a single composer or performer because there are so many popular versions. As somebody like me that didn’t live through the period, I have no idea which version came first.

In the case of Blowin’ in the Wind, I’m probably most familiar with Bob Dylan’s version, but Peter, Paul, and Mary and Joan Baez’s versions are equally known to me. I didn’t realize that Stevie Wonder, Dolly Parton, and Elvis also recorded this song (and many more have performed it live).

Of course, folk music of the 1960s was following the patterns that were set for music for centuries.

Before recorded music, hearing music live was the only option, and sharing songs had to be done via printed sheet music. Composers composed and musicians played, whether in a large orchestra or around a home piano.

Even at the dawn of the recorded music era, composing music was one craft, singing was another, and playing music was another. Judy Garland made Over the Rainbow famous, but it was also recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Johnny Mathis, and Dave Brubeck. None of them composed the song.

Songs of the early twentieth century were considered “standards,” and people bought records because they liked the singing voice of the performer.

Some pop music still follows this model, but many artists are now just that- no longer masters of a specific craft, but able to do several things with some proficiency. The Beatles could write, sing, and play instruments, and that’s become the standard for many acts that follow.

Songs are still covered by other artists, but music has also gotten more personal and specific. It’s hard to imagine anybody other than Kurt Cobain wailing on Smells Like Teen Spirit, right?

A good artist will also have a mastery of fundamental skills, but those skills are merely tools to creating something original and not the goal in and of itself.

I have always been drawn more to the artists than the craftsperson, whether that’s a chef like Jamie Oliver or a maker like Jimmy DiResta. Perhaps that’s a generational difference more than anything else. I was raised at a time when artistry was being celebrated and crafts were de-emphasized. It may explain why I find Fine Woodworking inaccessible, but will watch David Picciuto recreate a functioning Nintendo out of wood.

Yet, there will always be a need for people that can do a job well and are happy to contribute their piece to the greater whole. We have a shortage of skilled tradespeople in this country at the moment.

It’s very difficult to find a competent electrician, plumber, or carpenter for even basic repairs. I wonder if this is because we shifted what we glamorize in this country and a generation of potential craftspeople chased a different dream.

It seems that there should be room for both craftspeople and artists, and perhaps the pendulum will overcorrect in the next generation, favoring craft again. Or maybe we’re headed for a new territory none of us can imagine yet. Only time will tell.

What are your thoughts? Do you tend to favor learning a skill or experimentation and improvisation? Leave a comment- I’d love to hear what’s on your mind!

Related Reading

Don't Underestimate Jimmy DiResta

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Please consider sharing this with a friend that you think might enjoy it, or better yet, share it on social media so you can tell hundreds of friends!

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath