Before TikTok, There Was Channel 32

Living and working in the last glory days of public access television

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you like what you’re reading, you can sign up for a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox every Wednesday and Sunday and get my latest podcast episodes:

TikTok came under scrutiny last week when CEO Shou Xi Chew was grilled by the House of Representatives Energy and Commerce committee. At issue is whether the short form video social network, headquartered in China, could share private user data with the Chinese Communist Party. The very threat of this has caused lawmakers to propose a possible ban of the app in the United States.

I didn’t watch much of the committee hearing, but the few clips that I viewed after the fact highlighted the technological and generational divide between the people tasked with making the laws in our country and the citizenry upon whom those laws will be enforced.

The whole event gave me flashbacks to the presidential campaign of 2000. At that time, Lynne Cheney, the former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities and wife of Vice Presidential candidate Dick Cheney, appeared before a Senate committee to decry the violent lyrics of rapper Eminem. (We’ll circle back to this in a bit).

Thinking about TikTok and the young creators who grew up with the platform gave me pause to think back on my own career in television and video and to contemplate how different my origin story is in this industry, despite it feeling relatively recent to me.

I suppose this story could start further back, but I’m going to begin it around 1999 at this nondescript building in an office park in Mentor, Ohio. In my childhood, this building was the local home of Media One, our cable company.

As a teen in the late 1990s, I was quite intrigued by Channel 32, the public access channel. It was a completely mixed bag. Among the programs on air was Rosie’s Story Time where “Miss Rosie” (actually a high school Spanish teacher named Sharyn) would read stories to elementary school students, and North Coast Outdoors, where a local outdoorsman would talk about the best places to fish.

None of these shows was especially good or compelling, but there was something about them originating in my community which made them special. As a kid in suburban Ohio, the likelihood of a chance celebrity encounter or walking onto a film set was incredibly low. But the notion of running into Miss Rosie at the grocery store or the mall was comparatively high.

This all made the possibility of producing TV attainable. The programming originating from that office park in Mentor and was made in the community, for the community.

In 1972, as cable was just gaining traction in the US, the FCC mandated that by 1977, all cable systems would have to make production facilities and air time available to the general public.

It was argued that the air waves, which were home to broadcast television, belonged to the people (even though they functionally didn’t really). If cable was going to supplant broadcast television one day, space should be made available for the free exchange of ideas, which proponents said was central to a democracy.

When public access debuted, it was not without controversy. Producers made sexually explicit or vulgar content and programming was submitted from groups like the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Nation.

But by the time I came up in it, public access had matured and was enjoying a bit of a cultural moment.

Wayne’s World, the 1992 movie starring Mike Myers and Dana Carvey based on a Saturday Night Live sketch series, told the story of two friends that operated a public access show out of their basement in suburban Illinois.

We didn’t usually buy commercial VHS tapes, but in the early 90s, McDonald’s sold video tapes for below market rate. Somehow we ended up with a McDonald’s copy of Wayne’s World, and I watched that movie over and over as a young teen.

This was also the era of The Tom Green Show, an MTV version of a show that Green and his friends started on public access in Ottawa, Canada. The field pieces were seemingly all shot on camcorders and centered on Green’s strange interactions with other people.

My parents had an old camcorder that they let me play with, and my friends and I used to make short films that we would screen in school. The 25 kids or so in that classroom watched our work, but there was no way to share it outside of those four walls. There was certainly no way to go “viral” or to get “discovered.”

The TV industry was full of gate keepers that controlled what content got seen, and their power came from the incredible cost that it took to make high quality video work and the relatively sparse outlets that could distribute the work.

Inspired by Tom Green and imaging myself as the next Wayne Campbell, I looked up the number for Media One in the phone book one day and called them to inquire about making a public access show. I was 15 years old at the time. I was told that there was a training session that we would have to attend to go over the rules and policies of public access and tour the studio space, but that after that, we could have our own show. It felt like winning the lottery.

We suddenly had access to a studio space, video camera rentals, basic editing equipment, and even a stock music library to begin building out our show, and all for free. We decided on the name Neighborhood Freak Show.

When the show first started, we were too young to drive, so we had to get rides to our filming and editing sessions. The studio also didn’t allow us to use a ladder to adjust the lights on the grid because we were minors, so we often just turned on most of the lights in the studio and hoped we had something that looked good.

The show was mostly bad sketch comedy with some interviews and even an occasional band performing live. It’s nothing that I’m especially eager to showcase now, but it’s where I really had the freedom to try things and make mistakes that would serve me well to learn as a teen prior to becoming a professional.

Like any network show, we decided our run time should be a half-hour. Thinking of how teens share video now in six or ten second shorts on TikTok, it’s hard to believe that we were creating 30 minutes every two weeks or that anybody was even watching 30 minutes, but that’s just how TV was back then. We had to learn how to pace a half hour so that it was watchable, knowing that we were competing with every other show on the dial and it was easy to change channels quickly.

Perhaps the strangest moment in Neighborhood Freak Show history was a special guest that appeared on the show in 2000: Dick Cheney. At the time, Cheney was the running mate to George W. Bush and he made a campaign stop at our high school.

I had hoped to secure an interview with the candidate, but the people at my high school had very little information about who to reach out to with this request.

On the morning of Cheney’s assembly, I arrived at school to Secret Service snipers perched on the roof with assault rifles. It seemed unlikely that I wouldn’t get within 100 yards of the candidate. Still, I had brought my camcorder, just in case.

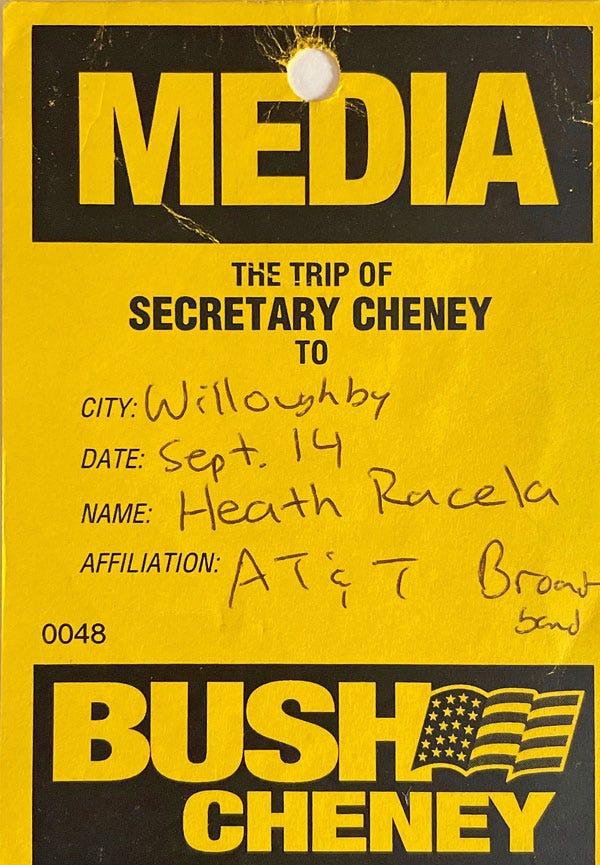

On a whim, I decided to leave class and walk down to the gym. There, I was greeted by a press secretary seated at a folding table. I explained that I produced a local public access show and wanted to cover the event. I expected to get turned away, but was instead simply asked to sign in and take my place on the press risers at the back of the room. Another public access victory!

I quickly felt out of my league. News camera operators from every local outlet plus national places like CNN were setting up long lenses on big, stable tripods. They plugged XLR cables into a distribution box that gave them a clean feed directly from the podium microphone. I had a handheld JVC camcorder in a pleather bag.

Cheney arrived and gave a speech about the problems with public schools, the need for school choice, and his support for voucher programs that would allow public funds to pay for religious education. It was an odd message to deliver in a public high school.

As the speech ended, the other news photographers began to ask each other about the location for “one on ones.” I realized that they were trying to sit down with Cheney to ask his opinion on tape.

We asked the press secretary about one on ones and were instructed to head to a classroom that Secret Service had secured. We were allowed to sit with print media and could record audio during the conversation but not video.

Cheney and his wife Lynne arrived, greeted us all, and sat down across the table from us. We introduced ourselves: “Bob Taylor, Cleveland Plain-Dealer; Janet Smith, USA Today; …Heath Racela, Neighborhood Freak Show.” Everybody chuckled.

Then the press began to grill Cheney over the latest scandal du jour; the issue which seems like a big deal in the heat of a campaign, but is usually forgotten in a few days.

During his speech, Cheney had discussed school safety, pointing a finger at the entertainment industry in particular. It had been a little more than a year since the shooting at Columbine High School. He was among the people that blamed the tragedy on violent video games and explicit music.

When it was my turn to ask a question, I inquired about the connection between violence and music. This was the era when acts like Marilyn Manson and Eminem were getting a massive amount of attention on MTV and seemed to be speaking to a very specific white male suburban angst that resonated with my peer group.

Unbeknownst to me, Lynne Cheney’s Senate testimony about Eminem was just a few days prior. Cheney invited his wife to answer my question and she went on to quote, quite graphically and fully from memory, several Eminem lyrics. It was disorienting to see a petit older woman in a business suit angrily saying things like “painting the forest with blood.”

Within minutes of the exchange, the Cheneys departed and our school snapped out of the dream-like state from that morning. Things returned to normal and we went back to class, having just sat across the table from the future Vice President.

From that experience, I learned a few things. Perhaps the most important was to always act like you belong somewhere even if you feel completely out of your league. Had I been sheepish in approaching the press secretary signing in members of the media, I likely would never had been credentialed to even cover the event, but something about the way I presented our little public access show made her think we were legitimate.

Neighborhood Freak Show ran for about 30 episodes in two years. It was a silly sketch show that had limited appeal outside of our high school peer group, but yet it could have been seen by other people in the community.

In that time, I learned how to pitch guests, how to edit, how to write, and even how to host. Some of these skills came in handy over my career in television, but I suppose it was even more useful when I launched the podcast three years ago.

I feel fortunate that I was able to do work that was public enough to generate some conversation and feedback, but was also still exclusive enough that it was mostly just being seen by my friends.

Teens today have the benefit of holding amazing technology in their hand that can allow for creative storytelling with minimal capital expense. But the downside is that everything is learned completely in view of the public. It’s one thing to have a joke not land for your classmates, but what about getting a mean comment from a viewer in another time zone or another continent?

Online videos also seem to live forever in a way that my show doesn’t. I have a box of VHS copies somewhere, but I haven’t watched them in maybe 15 years. In all likelihood, they may have deteriorated beyond the point of being watchable anyways. They exist in that beautiful time when the internet was starting to make our world a little smaller, but it wasn’t yet ruling our lives.

I’m grateful and nostalgic for the experience that I was afforded, but I am even more eager to see what Gen Z and those younger do when they step up to the content creation plate on a professional level. They are digital natives that understand the tricks of this trade at a deeper and more fundamental level than I ever will. I had to learn and discover the magic, but it’s ingrained in them.

One piece that I do miss from my late 1990s and early 2000s experience in television is the community aspect. There are still public access channels out there covering community events and meetings, but with cable cord cutting, that programming is less accessible than it used to be, especially if it’s not also streamed online.

Couple that with the near elimination of other local media outlets over the last generation and you have a citizenry that’s less informed about what’s happening in their own backyards.

I’m not sure if TikTok or other platforms like YouTube or Instagram fully fill that community void, but perhaps our definition of community is no longer about the people that live the closest to you, but the people that share your interests and sensibilities regardless of geography.

Whatever happens with TikTok in the coming weeks, there will always be a Lynne Cheney seeking to ban that which is new, provocative, or different. Hopefully the young people creating content these days can find a way to stay true to their own voice and get their work out, no matter the headwinds. It worked for me, and it all started with a phone call to Media One.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

If you enjoyed this issue, please share forward it to a friend or share it on social media:

Stay Safe!

Heath

Thanks for sharing your high school adventures. Very interesting. btw, are you still in the television world?