Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

I quit Amazon Prime last week after eight years as a member. This may not be surprising given how often I discuss my anti-consumerist and anti-consumption tendencies in this newsletter. But for many, including our family, Amazon has become the first and sometimes only choice for purchasing many, many things and it felt like it was time to change that.

I’ve been considering making this leap for a while now. Today I wanted to share some of the reasons why I decided Prime isn’t working for us anymore.

I can still remember the early joys of surfing Amazon.com in the late 1990s. Back then, the website was primarily a book retailer, although I also remember them selling related media like CDs and DVDs. Unlike Barnes and Noble or Borders, the two big players in physical media retail back then, Amazon had seemingly every title imaginable. I remember selecting books two or three at a time to qualify for “Free Super Saver Shipping,” which came with a $25 purchase.

But even in those early days, Amazon was already beginning to expand beyond just media. Looking at the image above, captured in 2000, there are already several tabs that give a hint as to where the site was headed: "Kitchen, Lawn & Patio, Tools & Hardware, Health & Beauty.” We may have all thought of it as a bookstore, but it clearly saw itself as a virtual Wal-Mart or Target.

In 2000, Toys R Us inked a deal with Amazon to be the exclusive Toy and Game retailer for the site. I worked at Toys R Us at the time, and it was very exciting news. Because of the partnership, our store computers were able to access Amazon.com (to check Toysrus.com inventory), and I can remember many slow evenings in the dark days of winter surfing the pages of Amazon on the store computer because there wasn’t much else to do.

The Toys R Us deal was meant to last for ten years, but Amazon soon reneged on the terms, selling toys directly and allowing other sellers to sell toy and baby products. Toys R Us sued and won, but it didn’t seem to stop the growth of Amazon.

It seems hard to believe, but Amazon Prime is a nearly 20 year old service, having launched in 2005. At the time, it cost $79 to receive free 2 day shipping for U.S. customers. In 2011, Prime members started receiving access to movies and TV shows ad-free. In 2014, Amazon debuted Transparent, its first original series. They also started Prime Music that same year.

I first signed up for Prime in 2016. At that point, we had two babies in our house and it seemed like the service was worth the cost. Our free time was limited and we could easily order refills of diapers, wipes, and cleaning products. The fee at the time was $99.

A few months later, I ordered an Amazon Echo speaker for our kitchen. I liked the ability to play music or add items to a shopping list hands free. It also helped that the Echo was tied to our Amazon account so I could easily say “Alexa, order more diapers” and an order would be automatically placed and shipped to us. It felt like living in the Jetsons.

As if ordering by voice wasn’t enough, I also purchased a Dash Button, which was an electronic experiment that Amazon launched in 2015 and then discontinued in 2019. Dash Buttons were small electronic buttons that automatically ordered a frequently purchased item when pressed. They were designed to be placed in areas like kitchen cabinets, laundry rooms, or bathrooms.

In hindsight, they were a giant waste in so many ways. We only had one Dash Button (for baby wipes), but there were literally thousands available. Each one had a unique brand or product line on them so you would know exactly what you were repurchasing. They gave the illusion of convenience, but in reality, they were a solution in search of a problem. Plus, they created a massive amount of plastic waste once Amazon bricked them.

We not only stopped using the Dash Button once discontinued, but around the same time, we decided that we didn’t like the Echo anymore. It felt too intrusive having a speaker that was always listening, and the costs seemed to outweigh the benefits. Our initial excitement about being Prime members and getting into the Amazon ecosystem was beginning to crack a bit.

In 2017, Amazon made the surprising entrance into the brick and mortar grocery space, purchasing Whole Foods Market for $13.7 billion. If we had any doubts about the value of our Prime membership, saving an additional 10% on sale items at Whole Foods seemed to make keeping Prime worthwhile.

We continued to automatically renew our Prime membership, barely noticing when in 2018, the price went up to $119 per year, or in 2022 when it was raised to $139.

The truth is, we had gotten hooked on the Amazon way of shopping- ordering something without having to worry about the shipping cost and knowing it would arrive to our front door within a day or so.

But I’ve been aware with some of the problems with that model for a while now.

In 2021, Amazon opened a distribution facility at the end of our street. I had never given much thought to just how many packages get delivered daily by Amazon until I had to see the nearly endless line of Sprinter vans driving down my otherwise quiet street or watching the vans fuel up at our local gas station at the end of a shift. The traffic was constant and the volume of packages just from this one facility was mindboggling. There are upwards of 1,200 such facilities in the U.S.

Around that same time, I began to notice the pileup of Amazon packaging in our house, especially those plastic bubble wrap white and blue mailers that so many small products seem to come in. They claim to be recyclable and Whole Foods stores accept them for recycling, but a CALPIRG experiment found that these plastics are often just discarded or incinerated.

When I look back at my buying history, I see some big shifts over the years. When we first signed up for Prime, we were mostly buying diapers, wipes, and specific kids’ clothes that were hard to find in local stores (things like rain boots). Our diapers and wipes were a natural brand that was not sold in many stores.

But more recently, our Prime order history shows items that could easily be bought in many stores but were ordered simply for convenience and often shipped as a single item order: dental floss, toothbrushes, batteries. While we didn’t use Prime aggressively, there were definitely times where it felt easier to simply order something for delivery than to pick it up at a store.

Even more remarkably as I scan some of my purchase history over the last eight years is how many items had to get returned or exchanged. Sometimes it was because of an error on our part- shoes that should fit our child but arrived too big or too small. But more often, it seemed to be because the products themselves were defective or damaged in shipping. It was becoming harder to trust the products being sold by Amazon, as many were low quality imports.

Amazon has been fighting against counterfeiters for years, with 15,000 employees devoted to preventing abuse of the platform in 2023 (out of a workforce of roughly 1.5 million). Still, the site seems to be riddled with products from no-name or off-brand companies, with no way to know the level of quality.

A simple search for “screwdriver” yielded more than 10,000 results. The top ones were from Amazon Basics (their private label) and Craftsman (the former Sears brand now owned by Stanley Black and Decker), but also options from brands with names like SUNHZMCKP, SHARDEN, and Amartisan. What?

Every time that I opt to buy something from Amazon rather than a local store, it’s not only taking money out of my community, but it’s weakening that local option too. I don’t want to get too far down this road where one day my local hardware store or clothing retailer or bookstore has closed, leaving me with SUNHZMCKP as my only option.

Because of its size, Amazon (and subsidiaries like Whole Foods Market) should have amazing efficiency and buying power that allows it to offer lower prices than the competition, but I’ve also been informally surveying that over the past few months and have found that to not be the case either.

To take one example, there’s a jar of Italian strained tomatoes that we purchase when we run out of homemade sauce. This past spring, it was on sale at the same time at both Whole Foods and Debra’s Natural Gourmet (an independent grocer in Concord, MA). Whole Foods price was $4.39, while Debra’s offered it for $2.99. The non-sale prices are more than $2 apart! ($5.49 at Whole Foods versus $3.39 at Debra’s).

I started watching the prices on some other items that we typically buy like bagels and cereal and started to notice that Whole Foods was almost always more expensive than small, independent grocers. This was the case at our old house in Eastern Massachusetts, at our new home in Western Massachusetts, and I even observed it in Florida over the summer when we stopped into an independent grocery store.

The independent grocers also routinely carried local produce in season, while Whole Foods produce was often imported from outside the U.S. entirely (something I’ve discussed before which also came up in my recent podcast with Austin Frerick.)

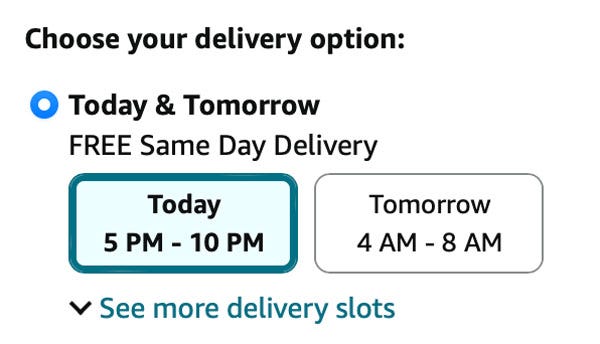

I have also noticed that Amazon seems to be prioritizing fast delivery at any cost, recently offering me delivery as late as 10pm or as early as 4am for a purchase.

It wasn’t that long ago that deliveries were only expected during working hours, Monday through Saturday. There’s something unsettling thinking about the worker driving a truck around darkened neighborhoods at 4am under immense pressure to make sure that we get the package that we don’t really need as quickly as possible.

The entire Amazon distribution system is full of well-documented worker safety concerns and union busting, so there’s clearly a cost to that fast delivery.

In the end, we’re not walking away from Amazon entirely. Like it or not, they are sometimes the best place to find obscure and oddly specific items. They do still offer free shipping for certain items or with a minimum purchase, it just takes five to eight days to arrive.

But for a while, I haven’t quite understood what Prime even was. It was a streaming service with amazing original shows like The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (check out my podcast episodes with Marin Hinkle and Michael Zegen from the show). But it also didn’t have a ton of worthwhile content beyond their headliners.

Prime was a discount club for Whole Foods, but it felt more like a CVS card than a Costco membership. And of course, it offered fast and free shipping, but I’m not sure that we really spent enough for that to payoff for us.

At any rate, I hope that by cancelling Prime we can be more thoughtful and intentional about where we spend our money, focusing on patronizing local merchants or buying used items when available.

Have you quit Amazon Prime? Have you resisted signing up at all? Or are you addicted to Amazon? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

I'm very proud, and quite vocal, about the fact that I've never been a prime member, and I've curtailed my amazon shopping to roughly 2 to 3 items Per Year for the past 10 years! Just as you mentioned in your post, I'm somewhat troubled by the idea of an amazon delivery person working odd hours in the morning or late into the night, just so i can get something that's not critical, at my doorstep in some ludicrously short time window. Not to mention the entire chain of people that have been overworked and underpaid to even get the items into the hands of the delivery people. The whole idea of this monolith merchandise outlet gobbling up all the regular, brick and mortar cornerstones' in countless town across the country is frankly nauseating. What ever happened to interacting with your community while out shopping? With going out of your house/apartment to connect with the environment and people in your town so that you can feel like you are part of something bigger? Sitting inside our homes and pushing buttons on our handheld supercomputers can be quite isolating, and in the end, we as a species are in fact very social creatures. It's not healthful to frequently shop on any of these applications, UNLESS you are physically limited and shopping in the traditional sense is difficult, try to get out of your home and do your shopping in person! Of course it's way more work, but work is good for us! it makes us stronger in many ways and helps you feel connected to your community.

p.s. Love that you mentioned Deborah's!! It honestly is my favorite place to shop. In fact, I am wearing my purple Deborah's apron as I write this response! lol

I have been fighting this good fight since Covid. People try to talk me out of it and even tell me to buy stock in Amazon. We never were big on Amazon to begin with. But increasingly I felt the need to turn my back on the leviathan and pay an extra $5 to $10 to buy directly from the manufacturer. Also, I do a lot of thrifting. More recently my local Facebook Buy Nothing group has been a delightful source of needed and not so needed products as well as removing the same from my home. Even so, I still sometimes order from Walmart and the product comes in an Amazon box, disappointing. Or a gift request comes with an Amazon link, I source the origin. I will keep fighting my one person war against a lazy consumer who loves the convenience while I love the unconventional.