From the Archives: A Newspaper Obituary

Looking back on a post from 2023, when it felt like print died

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

Today, I have another archived post to share with you, this one originally published September 10, 2023.

As many of us come to terms with the recent election results and rethink how we get our news (whether that’s corporate media, outlets like The Washington Post owned by billionaires, or tech platforms controlled by oligarchs like Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg), I think it’s worth rethinking the role of local journalism in our lives.

This piece feels newly relevant in that context, which is why I’m resharing it today. I hope it will spark some lively debate and conversations with all of you.

A Newspaper Obituary

While I know print newspapers haven’t really been a vital form of communication for a long time, this past week feels like the moment that physical newspapers really died for me.

I live in a rural-ish exurb at the fringe of Boston. We are close enough to the city that many of the people that live in our town commute in for work, but we’re also far enough away and surrounded by just enough farms to feel like we’re out in the country.

For example, my house has a septic tank buried in the backyard instead of a city sewer connection. The toilets all flush the same as they would in a regular house, but I have to occasionally have my septic tank pumped by a company, rather than just let my wastewater flow to who knows where.

We also don’t have curbside trash pickup provided by the town. There are private companies that will haul trash, but most people in town just take their trash and recycling to a transfer station in town once a week.

The transfer station is nothing more than a large parking lot with various dumpsters and compactors. Plastic goes in one bin, aluminum and metal in another. Glass, cardboard, and wood each have a respective receptacle. And so did newspaper. Or at least, it always did.

But when I went to the transfer station last week, the place where the newspaper recycling dumpster has been for the 15 years that I’ve lived in this town was empty. In its place was a few orange cones and a homemade sign instructing people to put their recycled newspapers in the cardboard bin, which has always accepted “mixed paper” as well.

My first job was delivering newspapers for The News-Herald, the local newspaper in my hometown of Willoughby, Ohio. I was thirteen at the time. My dad had been a paperboy when he was younger, so had my mom’s brother. Paperboy was a popular video game on Nintendo and Game Boy during my childhood. Being a paper carrier was a suburban rite of passage, a job that could be started at a younger age than working at McDonald’s or the local grocer.

I remember receiving a heavy duty shoulder bag when I first started with the paper. I thought I was so cool slinging it across my chest. I would wake up around 6:00 am seven days a week and walk around my neighborhood, dropping 25-30 newspapers on neighbor’s porches or between their storm door and front door.

The Sunday paper was so big that it came in sections that were delivered throughout the week. I would receive the ad inserts and comics on Thursdays, then another section on Saturdays (I forget which), and finally the news and sports sections on Sunday morning. Every Sunday before delivery, I spread out the piles of sections on our living room floor and hand assembled each paper.

As I got older, it got harder to wake up as early or get as excited about making sure the papers arrived on time. There were days when I was greeted by an angry customer, their morning routine thrown off because their paper was arriving at 8:00 am instead of 7:00 am. I never quite understood why they didn’t just watch the morning news on TV.

I had that paper route until I was about 16 or 17. At some point, I trained another neighborhood kid on how to do the route. Soon after that, the newspaper consolidated the routes. Instead of hiring teens to hand deliver the paper on every street or two in a neighborhood, they had adults drive around and pitch the newspapers into driveways from their car window. My grandparents, who had received the paper on their front porch for about 45 years at that point and were decreasing in mobility, hated the change and would complain about it often.

When I moved to Boston, the subway cars used to be littered with the free Metro newspaper. It wasn’t designed like a full newspaper, but was more like the early 2000s version of scrolling Twitter. The longest article was maybe six paragraphs. Many were just a sentence or two about something happening in the world, often accompanied by a photo. The entire paper couldn’t have been more than a dozen pages each day. Metro ceased publication in Boston in 2020, just a few months before the pandemic kept people home and off the subway.

As a college kid, I would occasionally buy a Sunday edition of the Boston Globe and try to read as much as could. It’s not that I was particularly versed in world affairs; reading the paper was just what I thought adults were supposed to do.

I think there may have been a brief period when I had home delivery of the Boston Globe as well because it was cheaper than paying the cover price each week. Suddenly, when the paper was there every week, it got read even less. I was already getting my news from TV and the internet. My attempts at being the adult my parents had modeled to me was thwarted by the changing tastes of my generation.

As a kid, I was fascinated by looking at reprints of old newspapers. I remember buying a replica of the edition when Neil Armstrong landed on the moon from the gift shop at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. and poring over the pages. The stories of the moon landing were interesting, but the old ads and other stories in the news in 1969 were equally as fascinating to me.

When big news events happened in my lifetime, I wanted my kids to someday have the same opportunity to look back at an old paper and feel a sense of time travel. I remember going out of my way to buy hard copies of the paper from my local corner store when Obama was elected, when Senator Ted Kennedy died, and when Michael Jackson died.

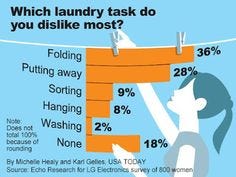

When I was growing up, we usually stayed at basic motels, but when we’d stay in a nicer hotel, my dad would show my sister and I how USA Today always had a graph or chart of some kind on the front page of every section. As I started working and stayed in nicer hotels, I liked reading the USA Today because of my dad. It was always strange to leave a hotel room early in the morning to see a hallway lined with a newspaper in front of every door, but that’s just how it was.

During my time at This Old House, it was pretty common to see old newspapers stapled to the insides of walls. It was an early and frugal attempt at insulation. My own wall cavities are now filled with cellulose, a type of insulation made from recycled paper, often newsprint. It makes a great insulation because it can be blown in to completely fill all of the voids in the wall cavity, and is treated to be fire and insect resistant. It never occurred to me when I had my walls filled with cellulose more than a decade ago that newsprint may become harder to come by. The shortage of recycled newspapers is something that cellulose manufacturers are grappling with at the moment.

Newspapers were also a staple in every antique store, used to wrap delicate purchases like ceramics and glass. Newspapers became filler when shipping packages and protection for items when moving. Newspapers also seemed better at starting a fire than just kindling alone. It’s hard to articulate just how ubiquitous newsprint was just a few years ago and now, it’s nearly obsolete.

It’s been at least a decade since I’ve read a print newspaper, probably longer. The newspaper vending boxes that once lined sidewalks have slowly disappeared. I’m not even sure if my local corner store still sells physical copies of the paper anymore.

According to the AP, U.S. newspapers have been closing at a rate of two per week. An increasing number of communities are left without any form of hyper local news. The disappearance of my transfer station’s newspaper recycling bin may not be a big deal in the grand scheme of things, but it feels like it’s symbolic of a much larger change in society.

The loss of a local journalism through a print medium makes me sad because it’s one less thing that the people in a community have in common. When news from any source can be instantly accessed in the palms of our hand at a moment’s notice, we can all choose to read the news we want to. Local newspapers not only printed the mundane, such as the local honor roll or little league scores, but they also kept local politicians in check and accountable.

Reflecting back on it, I miss printed newspapers, even if they never quite became my thing. They were a ubiquitous part of the culture whose demise was both drawn out for decades and somehow swift.

What do you remember about your local newspaper? Did you write for one? Deliver one? Or are you still a print reader? Leave me a comment- I’d love to hear your story!

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

Don't Take the Election Personally

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

I was visiting my parents last week, and they had an entire trunk in their basement filled with laminated newspaper articles, mainly from when I played sports in high school - being the Plain Dealer Player of the Week for cross country, being selected for the News Herald Track and Field All-Stars or that kind of thing. I'm sure similar online honors exist for today's young athletes, but Googling yourself can't have the same thrill as buying a paper and flipping to the back of the sport section to see if your name or photo made it in to the weekend coverage.