Losing Our Religion

If we're becoming a country of "nones," what does that mean for our shared sense of ritual and rites of passage?

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

I’ve been reading Jonathan Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation, which is about how the wide adoption of smartphones in the 2010s has led to unprecedented rises in preteen and teen rates of depression, anxiety, and even suicide. (Haidt also publishes

here on Substack).Haidt looks carefully at data from all over the world, and his conclusion is that easy access to social media, video games, and pornography in our individual devices have been a major cause for the rapid deterioration of our children’s mental health and well being.

But Haidt also raises some interesting points around how societal changes that have been taking place over the last several decades have left many kids feeling unmoored and adrift even before smart phones accelerated these feelings.

Haidt describes how societies have always celebrated certain milestones like the birth of a child, marriage, and death. In nearly every culture around the world, there was also a celebration of puberty and the transition into adulthood, which involved three parts:

“In 1909, the Dutch-French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep noted that rites of passage around the world take the child through the same three phases. First, there is a separation phase in which young adolescents are removed from their parents and their childhood habits. Then there is a transition phase, led by adults other than the parents who guide the adolescent through challenges and sometimes ordeals. Finally, there is a reincorporation phase that is usually a joyous celebration by the community (including the parents), welcoming the adolescent as a new member of adult society, even though he or she will often receive years of further instruction and support.”

According to Haidt, since the early 20th century, these rites of passage around puberty have started to disappear from industrialized societies:

“Such rites are now mostly confined to religious traditions, such as the Bar and Bat Mitzvah for Jews, the quinceañera celebration of a girl's 15th birthday among Catholic Latin Americans, and confirmation ceremonies for teens in many Christian denominations. These remaining rites are likely to be less transformative than they once were as religious communities become less central to children's lives in recent decades.”

Haidt is exploring how the disappearance of certain rights of passage affect the transition from child to adult, but lately I’ve been considering the broader point of what does a society look like that is stripped of rituals, routines, and customs?

I come from a pretty religious Catholic family. Both of my grandmothers (my mom’s mom and my dad’s mom) regularly prayed the rosary. Even if my parents had their reservations about the Catholic faith, they raised my sister and me in the church. From an early age, I seemed to take to it like a fish to water.

When I was in second grade, a charismatic young priest joined our parish. He was known for belting hymns quite loudly and for his fire and brimstone sermons that reminded me of Karl Malden’s performance in Pollyanna. This young priest brought a new life to the experience that my friends and I imitated on the school playground.

Like many folks who ultimately ended up in the entertainment industry, Catholic Mass was the first exposure that I had to theatricality. There was music, fire (candles), smoke (incense), a three act structure, long before I ever saw a Broadway play.

For a brief time in elementary school, I even considered a career as a priest.

But even as I seemed “all in” for Catholicism, some cracks were starting to form in my faith.

It started with some of the unanswerable questions that many people struggle with. How could I be certain, for example, that our way of praising God and celebrating sacraments was correct? After all, there were Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, and many, many other people around the world who equally felt that their way was the correct one.

When these questions were raised to teachers at my after school religion classes, the answer given was that I had to have faith, and to even ask questions like this was a betrayal of that faith.

Even with these cracks, I still attended church regularly and participated in the sacraments like Communion, Confession, and later Confirmation.

Life in the church didn’t just give me a way of interpreting the world, but it also helped to mark the passage of time. There was the arrival of the Advent wreath in early December, where one candle per week would get lit leading up to Christmas. There was the rituals around Easter and the seemingly unremarkable “Ordinary Time.”

But as I grew older and my questions remained unanswered, I began to drift away from the church. The answers I was seeking were more present in the world around me- in the trees, in the forest, in the ocean, and in my own thoughts.

This was also around the time that the Catholic Church sexual abuse crisis was becoming well known, starting in my new hometown of Boston, but spreading worldwide. That charismatic priest that I had so admired in my youth was revealed in 2002 to have groomed and attempted to sexually abuse a teenage boy. He was removed duties that would involve direct contact with community members (although according to new reporting, he is still serving as a priest and has been at the center of new controversy that is not sexual in nature.)

My final break with the Catholic Church came during a visit to Italy in 2012. I hadn’t attended a Mass in years at that point, but thought a visit to the Vatican might be clarifying in some way. It really was.

As I walked through the massive hallways and rooms and saw gilded murals hand-painted by some of the world’s greatest artists, intricate mosaic floors, and marble statues, I couldn’t help but think of what the life was like for an average Roman living near the Vatican hundreds of years ago when the priests, bishops, and popes were living lavishly. I remembered how in religious classes, we were given our own donation envelopes as kids and encouraged to tithe long before we were old enough to even have income. Were we funding the less fortunate in our communities or were we funding a life of luxury for priests and the administrative heads of the church?

Prior to that trip to the Vatican, I would still sometimes identify as Catholic, but after that trip, I no longer did.

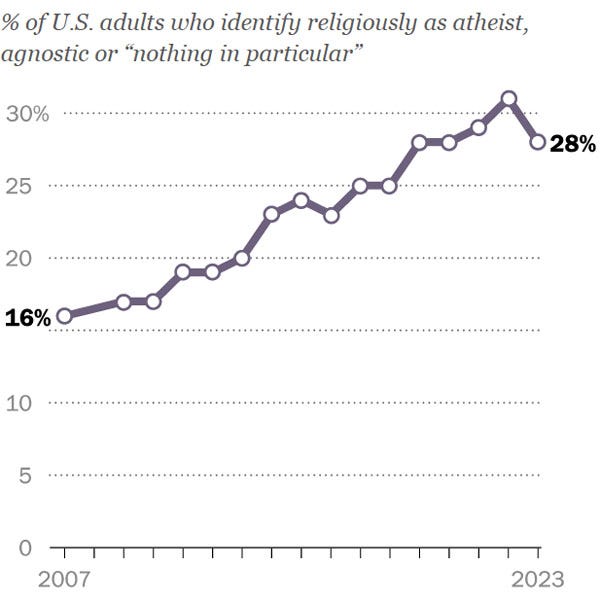

I had officially joined the ranks of the religious “nones,” U.S. adults who identify as atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular” according to the Pew Research Center. Religious “nones” have been making up an ever increasing part of the population, from 16% of U.S. adults in 2007 to 28% in 2023.

It has been reassuring to know that I can look for answers in the stars and the wind that seem to fit my life better than the construct of a God who is tallying your good and bad deeds and will judge you on your last day. But what I have missed, and what Jonathan Haidt has described is missing in all of us at large, is the predictability of the calendar and the rites of passage that mark our time on this planet.

We still celebrate Christmas with our kids (who have been raised without any religion), although it’s a secular version of Christmas. It’s a celebration of light during the darkest days of the year that involves bringing an evergreen tree into the house when so much of the outside world is bare and cold. Our version of Christmas does not involve a manger, shepherds, or wise men. Celebrating light in a time of darkness is also at the root of Hanukah, Kwanzaa, and the Winter Solstice, all celebrated around the same time.

Similarly, Easter is a time of rebirth, as the trees around us come alive with new buds, the grass turns green again, and the baby bunnies are born. But it’s not a time where we discuss persecution and crucifixion.

This lack of a religious anchor has not always been an easy journey. Most of our cities place some kind of religious building at the center of town. In this country, this tradition started with New England “meeting houses” where town meetings, elections, and long Sunday services were held. Their white steeples still dominate many small towns in our region, rising above the tree line and visible from a distance.

I’ve described in the past how in my hometown of Willoughby, Ohio, the Methodist church is sited around the downtown park, surrounded by some of the most important secular buildings in the city including the city hall, library, and the original high school. The Catholic Church that I grew up attending sits a few blocks to the south, in a prominent place on the main street, which once carried streetcar passengers between Cleveland and Painesville.

Haidt, himself an atheist, devotes an entire chapter of The Anxious Generation to looking at the role organized religious practices around the world have played in helping us form community that elevates our spirit and makes us feel larger than just individuals:

“Émile Durkheim showed that human beings move up and down between two levels: the profane and the sacred. The profane is our ordinary self-focused consciousness. The sacred is the realm of the collective. Groups of individuals become a cohesive community when they engage in rituals that move them in and out of the realm of the sacred together. The virtual world, in contrast, gives no structure to time or space and is entirely profane. This is one reason why virtual communities are not usually as satisfying or meaning-giving as real-world communities.”

Haidt believes that we can find replacements for many of the benefits of organized religion, but he also points out the importance of communal activities like singing together, dancing or moving together, or sitting in silence and meditation together.

Like Haidt, I can see the benefits of spiritual practice, but also think it is important to acknowledge the harm that religions around the world can do. Many organized religions suppress the feelings, authority, and autonomy of women. Many profess to help the less fortunate, while continuing to build temples for leaders (whether actual temples like the Vatican or the mansions and private jets that many Evangelical leaders in the U.S. enjoy today).

As our world continues to evolve into a “post-religious space,” I agree with Haidt that it will be important to find secular ways to tap into the divine part of our nature, and to mark the passage of time and the growth of our community members. How we do this is an ever-present question in my own mind, one without ready answers. But I do know one thing: the answers no longer lie in the bureaucracy of a large church, but somewhere else. Somewhere where community and nature define us.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Growing up and out of the conservative Black church, I feel this so much. I’m about to dig into D. Danyelle Thomas’s The Day God Saw Me as Black that touches on how this is looking for a lot of us Black folks socialized as women.

I was raised Jewish, but I have walked away from organized religion for several reasons. Not least, the Temple prioritized those who supported the Temple financially. Even now, when I refuse to "Stand with Israel" (I stand with all the victims regardless of citizenship or religious affiliation) and point out the atrocities of the Netanyahu administration, I am vilely, and I mean words I won't write here, by friends and family. I've asked them how their blind loyalty differs from MAGA's, and that pisses them off even more. Tribalism helped humanity survive and flourish for millions of years and may eventually destroy us.