Maple Season circa 1830

Visiting the nineteenth century to learn about the origins of maple syrup

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered in your inbox twice a week:

Last month, I described in detail my method of making homemade maple syrup. I always like to imagine as I collect sap from aluminum buckets hanging on my backyard trees that I am part of some larger tradition going back generations.

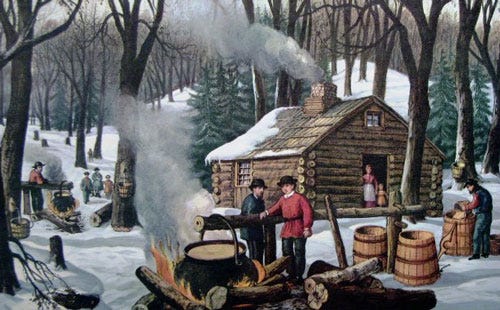

As I trudge through my suburban backyard in a water-repellant Carhartt jacket, I think that I am not that far removed from the characters in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s writings or a Currier and Ives print. After all, making maple syrup is a natural process that is as old as the forests.

At least, that’s what I always thought. Or more precisely, I actually hadn’t given it much thought at all. Maybe I have been allowing a nostalgic version of the past live in my head completely unchecked.

I didn’t intend for a visit to Old Sturbridge Village to completely change my perception of maple syrup, but that’s exactly what it did.

Old Sturbridge Village is a living history museum not far from me, although to call it just a “museum” is an understatement. The Village recreates life in a rural New England village in the 1830s. It features more than 40 structures, most that are true historic buildings that have been moved from their original homes to form a new “town.”

Walking around the Village is a bit like walking through a Hollywood backlot, but it’s also much more real. Buildings are not merely facades, but they have period interior spaces as well. And more importantly, everything works.

There are fires in the fireplaces, live chickens in the barns, and real sheep grazing in the meadows. There are shoemakers sewing leather shoes and potters making earthenware on a foot-operated potter’s wheel. There’s a meetinghouse at the center of the Village and working mills and a working farm at the outskirts.

This time of year, Old Sturbridge Village hosts Maple Days, which showcase how early Americans would have collected maple sap and refined it into something useful. As with everything at the Village, costumed interpreters not only explain how things were done, but they show you.

My first lesson at the Village was that the finished maple syrup that I make and bottle was nowhere to be found. Here’s a photo of what the people in the 1830s were after instead:

These brown loaves are solid blocks of maple sugar, which are produced from refining maple sap even further than I do. Maple sap is clear when it runs out from the tree. As it’s boiled down and reaches about 7ºF above the boiling point, it becomes the maple syrup that we pour over our pancakes and waffles.

These days, we understand the canning process, which involves creating a vacuum in an airtight container. By canning maple syrup, it becomes shelf stable for more than a year. But that technology did not exist in the 1830s, so there was no way to properly store maple syrup and it would spoil quickly.

Instead, the Village demonstrates how in the early 1800s, the maple sap would be left to boil well past the point of syrup to about 45 or 50ºF above the boiling point. It would then be poured into a clay pot with a wooden plug in the bottom and would be left to cool.

When the wooden plug was removed, any liquid left in the sugar would drip out. That liquid is maple molasses, and it would be used to sweeten baked goods. The solid pieces would become the maple sugar loaves and they could be wrapped in paper and stored away from pests. Because all water had been boiled away and drained off, the sugar was shelf stable and could be stored year round.

For many New England farm families of this era, the amount of sugar that the maple sugaring process provided was more than sufficient to meet their needs. According to Jennie Rothenberg Gritz in Smithsonian Magazine, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the average American consumed about six pounds of sugar per year. Today that average is 130 pounds!

Our ancestors had a very different relationship to sugar, as I learned when speaking with Tom Kelleher, historian and curator of mechanical arts at Old Sturbridge Village. Tom explained the origins of early American attitudes towards sugar:

“In medieval Europe and early modern Europe, sugar was not so much something to eat, but it was a spice, it was a flavor, like pepper, like salt. That’s anywhere from 1,000 years to maybe 250 years ago. Until the late 1700s, most people are not consuming very much sugar, under five or ten pounds a year and mostly then as a sweetener. People by the Village period, the 1830s, are eating twice as much sugar at their Colonial parents and grandparents had consumed, so sugar rise in America has been going up for a long time.”

Tom went on to describe the macroeconomic forces at work that led to an increase in sugar consumption, especially cane sugar grown in the Caribbean:

“As per capita wealth rises in America, as trade connections become quicker, easier, and cheaper, as the exploitation of enslaved people continues to expand, and as sugar refining technology improves, prices of sugar go increasingly down and so more and more people want it, can afford it.”

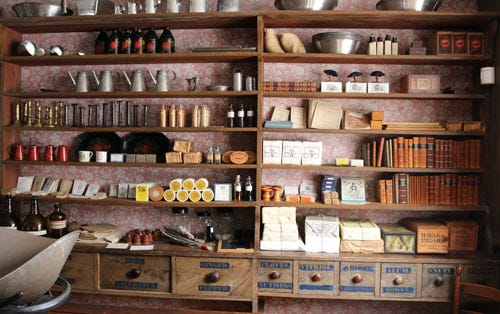

Cane sugar would have been sold in general stores and country stores in the 1830s, but for rural New Englanders, there were many reasons to make maple sugar at home. For one, it was practical. Aside from the labor to collect the sap and the firewood used to boil it down, the maple sugar was essentially free.

Some New Englanders of this era also opted to avoid products made with enslaved labor, which may have motivated home sugaring for some as well.

Whether the sugar came from Caribbean canes or Northeastern forests, demand rose as uses for sugar in everyday life increased. Again quoting Tom Kelleher:

“It starts as sweetening tea and coffee, then having sweet baked goods: cookies, cakes, and pies that are increasingly sweetened are more and more popular. And the use of sugar as a preservative, like salt, in terms of things like jellies, jams, and fruit preserves, a way to take your perishable summer berries and enjoy them in the winter. [Berries] don’t really lend themselves to salting but they do lend themselves to making something so sweet that no microorganism can deal with it.”

Of course today, we have tons of sugary options like soda, candy, and cookies. But sugar is also “hiding” in nearly every other processed food we eat, including pasta sauces, salad dressings, yogurt, and oatmeal, which may help explain why our sugar consumption today is about 21 times higher than it was about 200 years ago.

Even if the end goal of our ancestors tapping maple trees is different than mine, the process for collecting maple sap and refining it are still very similar to my home operation.

I drill a hole in my maple trees at about chest level, then install a metal tap to remove the sap from the tree. A metal bucket hangs from that tap on a hook and a metal lid keeps the buckets covered to prevent melting snow, dirt, or other debris from contaminating the sap.

At Old Sturbridge Village, the general principle is the same, although the tools they use are quite different.

The taps are crafted out of staghorn sumac, which is shrub that grows in New England. The center core or pith of sumac is weak and can easily be pushed out with a small stick, leaving behind a hollow channel in the branch.

A jack knife is then used to whittle a chamfer on one end, which helps keep the tap from splitting when it freezes and allows the sap flow to start sooner each morning. The other end is also whittled with a jack knife to form a taper. The tree is drilled to accept this taper and voila- a maple tap the 1830s way!

The taps are installed low to the ground and the sap drips into a carved log instead of a bucket. On the morning that I visited the Village, the temperatures were below freezing so the sap was not flowing, but you can get the idea of how the sap would drip out of the tree.

The log troughs were traditionally made from a wood like poplar because it has a straight grain and doesn’t impart a flavor into the sap. The log is split open and then a trough is carved to hold the sap using an axe-like tool known as an adze. Carving the logs was traditionally the work of the young boys of the household.

Sap is collected from each trough, often into a water bucket or milk bucket, where it could be stored until it was time to boil.

The boiling process happens over a fire to evaporate water from the sap and leave behind either maple syrup or maple sugar. At my house, I use a homemade wood stove with stainless steel trays for this.

At Old Sturbridge Village, they have a sugar camp, similar to one that would have been in the woods amongst the maple trees in the 1830s. The center of the sugar camp is a fire pit made with field stones. A branch is propped over a roaring open fire. On one end, the branch rests on a natural piece of ledge and on the other end, it’s wedged into the crotch of an old tree trunk.

The cast iron kettles used for boiling down the syrup were the same pots that were already in the household- no speciality equipment was required. The larger pots were sometimes used for laundry, whereas smaller ones would have been used for cooking in the hearth.

One place where I felt kinship with the old Yankees is in their use of scrap wood for firewood. I refuse to buy firewood for my maple operation but instead prefer to use branches that have fallen on my property and scrap wood from my woodworking projects.

According to the interpreters at Old Sturbridge Village, an outdoor firepit like they have on exhibit is a great way to make use of old fence posts or other lumber that was too big to burn indoors. It was nice to see nails still embedded in some of the wood at the Village, as it had clearly been used for other purposes before being destined for to burn. An outdoor fire pit is also a place to burn woods like pine, which release creosote into chimneys and should not be burned inside.

After boiling outdoors, I tend to move my syrup onto the stove to complete the final boil. There, I can closely monitor it with a candy thermometer to know the precise moment when it’s done. In the 1830s, they simply used a ladle from the kitchen and watched to see how the sap fell off of it to determine when the sap was ready to pour into sugar molds. The finished sugar loaves would have been made at the sugar camps in the woods, and this entire process would have been the purview of the men of the family.

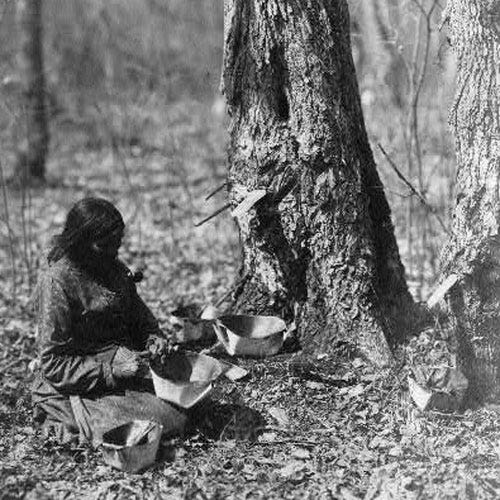

The methods seen at Old Sturbridge Village depict the process in the 1830s, but the early European settlers would have learned the initial concept of maple sugaring from Indigenous People, whose tradition stretches back much further.

According to the Massachusetts Maple Producers Association:

“The most common early method of collecting this sweet sap was to make V-shaped slashes in the tree trunk, and collect the sap in a vessel of some sort. Not having metal pots in which to boil the sap, the Native Americans boiled away the water from their sap by dropping hot rocks in the containers made of hollowed out logs, birch bark, or clay.”

In some ways, visiting Old Sturbridge Village for Maple Days felt like a homecoming. Many of the steps in the process felt familiar and I could draw a direct line between how old Yankees collected sap and how I make maple syrup.

But I was also quite surprised to learn that the maple syrup that I prize today was relatively unknown to people living 200 years ago. According to Tom Kelleher at Old Sturbridge Village:

“Syrup doesn’t become a big thing until like the 1930s. You start to see it available commercially by the 1880s, but it doesn’t really get any traction until the 1930s and surpass maple sugar as a commodity.”

According to one report, Vermont didn’t begin marketing its ties to maple syrup until the early 1940s. The use of a maple leaf as a symbol of Canada only began in the early 1800s. It was adopted onto the Canadian flag in 1965.

Of course, today the maple syrup industry is massive and maple sugar is hardly known or valued. According to Grand View Research, “the global maple syrup market size was valued at USD 1.49 billion in 2021.”

After reading the work of Dr. Steven Gundry (and chatting with him last year on my podcast), I became aware that many of the food ideas that we hold as “traditional” are relatively recent developments. For example, he talks about tomato sauce becoming associated with Italian food within the last 200 or so years. When considered along the continuum of human evolution, many food ideas that we take for granted, including high sugar consumption, are very recent developments, which may explain why our modern diet does not always seem compatible with our bodies.

Regardless of how we arrived at this point, I am thankful that I live in a time where I can enjoy maple syrup with my breakfast on occasion but that I can still have a connection to the old way of doing things, even if that old way isn’t quite how I imagined it for all of these years.

Maple Days runs through March 19 at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA. You can find more information about the event here.

Disclosure: Old Sturbridge Village provided complimentary admission to the museum for this story.

Related Reading

At the Corner of Washington and Summer

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

If you enjoyed this issue, please share forward it to a friend or share it on social media:

Stay Safe!

Heath

I’ve heard of maple loaves, but I never knew much about them. It is really awesome that maple sugar was an early “free trade” option as a sweetener. Learned a lot today!