Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

In my former role as a producer on Ask This Old House, I would occasionally come across an interesting relic in the backyards of Boston and the adjacent suburbs. Here’s a photo of what I used to see:

These hinged metal lids with a foot pedal resemble a small sewer cover, except they lead to a shallow underground metal bucket which is usually surrounded by concrete. Can you identify what it is?

In the early years of the twentieth century, these bins used to hold household garbage underground until it could be collected. At the time, garbage didn’t mean everything that gets discarded, but instead was specifically food scraps and organic waste. Dry paper waste was known as rubbish, and it was collected curbside in metal bins, very similar to how we treat all of our trash today. According to WGBH, collecting the organic “garbage” was much more work:

“…the garbage men came through twice a week. And it was grueling work, pulling heavy, garbage-filled, metal bins up from the ground, lugging them from the backyard to the garbage truck at the curbside, emptying it, and then returning it, at house after house.”

By being buried underground, the garbage was kept cooler, which slowed down the rotting process and hopefully helped contain the smell. The heavy metal lid helped keep rats, mice, and other pests from getting to the food scraps.

These subterranean garbage cans are still available for sale brand new, although they are no longer a fixture of urban backyards, and instead are marketed as a way to keep trash out of sight at condo complexes (although I don’t know that I’ve ever seen them used for that purpose).

While the notion of sorting and collecting waste separately has historic roots, many municipalities have revived some version of this model, collecting food waste separately from recyclables and trash. That food waste is sent to composting facilities where it is broken down into a useful soil amendment.

But back in the era of the buried pail, the garbage was used for a very different purpose. Instead of decomposing in a compost pile, the food waste was actually fed to pigs as slop. It’s not that the pigs would have gone hungry without city dweller’s garbage or that farmer’s needed a low cost source of food. But before the plastic garbage bag was invented in the 1960s, trash could quickly get gross, so separating wet material from dry material made more sense. Feeding the organic matter to pigs was simply a smart way to make use of the garbage, turning it into protein (in the form of loins or bacon) rather than methane.

The idea of collecting food scraps in the city and feeding them to pigs on nearby farms may sound odd, but in principle, this cycle was common on farms for centuries. We think of farms as specialty operations these days- a farmer grows corn or soy beans, or raises chickens, but the notion of a specialized farmer like that is relatively new.

At one time, most farmers grew a diverse selection of fruits, vegetables, and grains while also raising animals. The food grown on the farm would feed the family, would be sold to other families, and would feed the animals.

Animal waste is a natural source of nitrogen, phosphorous, and other nutrients and it adds organic matter to the soil. So the animal waste made on the farm was able to be used right back on the fields of the same farm to nourish crops. It’s an efficient, closed loop system that’s incredibly low cost.

Food scraps were also disposed of right on the farm. Susan M. Kennedy published a remembrance of her experience growing up as a farm child, collecting food waste in the kitchen like onion skins and carrot peels, feeding some to the dogs, and taking the remainder out to feed her pigs.

Taking waste from the cities and bringing it to local farms added a new layer to the process, but the pigs that were fed city waste were still being consumed locally, so the footprint of the whole operation was relatively small.

In the post World War II era, farmers were sold the idea that businesses could provide a better solution than Mother Nature. Chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides replaced manure and that cycle of waste disposal was broken. Commercial animal feeds and even processed dog foods became more common. Food scraps and manure no longer fulfilled their role in the cycle. In this same era, farms became specialized operations, focusing on only one or two types of outputs rather than a little bit of everything, a trend which continues to this day.

Livestock are now raised at CAFOs, or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. In these facilities, animals may spend their entire life indoors, crammed together in small spaces. Animal waste is abundant, is stored in large anaerobic pits, and can often contaminate nearby water supplies. These large-scale meat production facilities are often clustered in certain regions, removing a link in the local supply chain.

I’ve written before about feedlots like these, where most of the meat Americans consume originates. If you missed that piece, this video from the New York Times does a great job demonstrating just how dire the living conditions in these places can be:

But specialization is not only a problem for meat production. By moving livestock off of a diverse farm, it means that the animal waste is no longer readily available as a free, natural fertilizer. Chemical fertilizers have to be purchased, transported, and applied to the fields instead. Herbicides like glyphosate are used to control weeds.

Feedlot meats and in-ground food scrap containers came to mind when I recently came across a story in Civil Eats from Lisa Held looking into Do Good Foods, a company which is turning grocery store waste into chicken feed.

Held lays out the problem that Do Good Foods is trying to solve:

“About 35 percent of food produced in the U.S. is wasted each year, and much of it ends up in landfills, where it emits methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Despite a 2015 pledge to halve its food waste by 2030, the U.S. has since increased it instead. At the same time, climate experts are now emphasizing the fact that cutting methane emissions is a critical piece of avoiding catastrophic climate outcomes.”

In her piece, Held tours Do Good’s manufacturing facility in Pennsylvania and describes the process of turning unsold or spoiled grocery store food into chicken feed:

“Situated in the same industrial park as Metals USA and Future Foam, Do Good’s facility cost $170 million to build…”

“Inside, large, green bins were filled with surplus food from 450 supermarkets in the region. Soon, a conveyor belt would move them toward a giant metal claw. As the claw lifted each bin, the lid would swing open. Bruised apples, watermelon rinds, unsold hot dogs, and stale bagels would fall into a chute, initiating the process of turning grocery store waste into chicken feed.”

“After the food scraps move through the initial chute, they are sorted and assessed for quality along a conveyor belt, ground into small pieces, and then moved into huge, heated tanks that look like stock pots made for hungry giants. In the tank, a massive metal arm stirs the mixture constantly as it cooks, turning it into a nutrient-rich broth. If you’re standing over the tank breathing in the steam, it smells like a brewery.”

“Eventually, after the excess fats in the mixture are removed via a centrifuge, the nutrient stew is pumped through a system of white pipes until it comes out as flaky sheets that become a powder when you crush them in your hand. The final product will get loaded into the grain silos and then into a tractor trailer. Once it reaches the farms, [co-founder and co-CEO Justin] Kamine says, the growers turn it into pellets and add it to the chickens’ feed as a supplement to their usual corn- and soy-based diet.”

There’s no denying that the food waste problem is real, and Do Good is making an attempt to solve that. However, as I read these descriptions, I was skeptical. Processed food is processed food, whether we’re talking about potato chips or cereals for human consumption or feed for chickens.

Do Good not only makes the feed, but they also market their own line of chicken that is raised on the feed. The chicken farms are located in Delaware, and while Held does a good job pressing the Do Good representatives in her piece, she was not granted permission to tour the farms. She was also not given clarity on how the chickens are raised on these farms:

“When asked about climate-conscious consumers who might also be concerned about factors like pollution from CAFOs or animal welfare, Kamine pointed to the claims that appear on the product’s labels: natural and cage-free. However, the current U.S. Department of Agriculture standard for “natural” does not apply to farm practices in any way. Cage-free is also meaningless when applied to chickens raised for meat, as cages are only used in egg production, a fact [co-founder and co-CEO Justin] Kamine acknowledged after it was pointed out.”

I feel for the average consumer who is trying to make consciously better choices at the grocery store. The package of chicken that Do Good sells contains lots of positive descriptors: “No antibiotics- ever,” “100% natural & cage free,” “Our chickens are raised on a diet including nutritious surplus grocery food,” “You can fight food waste and combat climate change from your kitchen.” In every respect, this product sounds superior to the store brand chicken sitting in the same cooler. But there’s no way to tell if these chickens are being raised in a windowless steel building with thousands of other birds or are roaming the idyllic pastures of Delaware from this label. And Do Good seems just fine with that being murky, which makes me suspicious.

To her credit, Held also describes another chicken supplier, Green Circle Chicken, which collects food scraps from restaurants in New York City and brings them to Amish farms in Pennsylvania. There, the birds are raised outdoors and fed the actual food scraps, not a processed version of them. Many of the restaurants that contribute their scraps also serve the finished chickens on their menus. It’s closer to the model of hog slop that I described at the beginning and one that just feels more logical.

Held also notes that perhaps the best way to deal with waste in the food system is to try to reduce it at the source, rather than to find a use for it after it has been generated. I tend to agree with this perspective, although I also know that it is easier said than done.

In my opinion, part of the solution needs to be consumers shifting more of our food dollars to local growers and producers. When you can purchase produce at a farm stand a few steps from the fields, there is inherently less waste at every stage. It takes less fuel to transport and refrigerate, there’s less packaging, and there’s less of a chance of food being discarded because of spoilage en route because its being sold at the height of freshness.

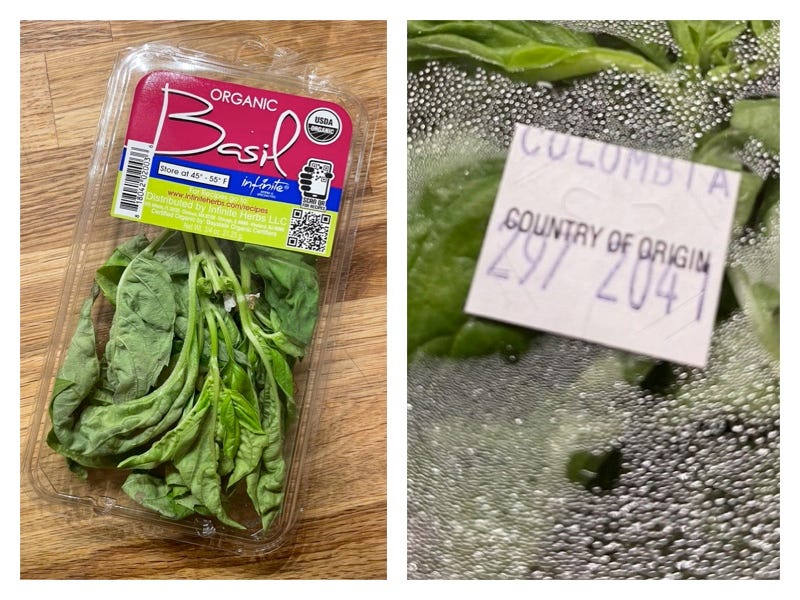

As I wrote in an essay looking at author Wendell Berry and specialization, supermarket buyers are often only interested in maximizing profit, and they tend to make decisions that I view as penny wise, pound foolish. I recently had to purchase basil and my local supermarket only had one option, sold in a plastic clamshell case. Upon bringing it home, I noticed that there was a small label on the back of the package that identified this basil as being from Colombia.

I can grow basil with some proficiency on my kitchen window sill. It can certainly be grown in a green house here in the Northeast, or in the ground in the Southern U.S. at this time of year. However, this supplier decided that the most efficient way to bring basil to my local supermarket shelves was to import it from another continent. Of course there is abundant waste in the supermarket system when the overriding logic is cost efficiency above all else!

For those of you that are interested in eating more locally and seasonally, I have offered some advice in past issues of this newsletter. Truthfully, it can be done in small, incremental steps.

Start with one food item- maybe buying eggs from a neighbor with chickens. Or commit to visiting a local farmer’s market more often. I started by buying local produce when it was in season more than a decade ago, and now we purchase nearly all produce, meat, eggs, and even most dairy products from local sources year round. If we can’t buy directly from a farm, we shop at local markets and health food stores whenever possible, minimizing the amount of time and money we spend in traditional supermarkets.

Buying locally also allows you to get to know your farmer personally and to ask questions about their growing practices. This direct relationship can be more beneficial than relying on the marketing messages printed on product labels, which can be misleading when it comes to how food was grown or raised.

I get skeptical when I hear that the best way to solve a problem is to introduce technology and a new product. Yes, food waste is a problem. But is the best solution really to accept our current levels of waste and manufacture a product that relies on that waste? Or should we be examining the entire system to solve it?

We may never go back to underground garbage bins in cities to feed nearby pigs, but perhaps that notion is due for an update.

What are your thoughts? I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Related Reading

Getting Acquainted with Wendell Berry

Where Can I Get a Good Burger?

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath

I feel pretty good about eating a meat free diet. We belong to a CSA and freeze a lot of soup each season. We have an garden every year also. So, we're trying but I'd say we're still only about 60%. Packaged cereal, oils, and dairy free products are hard to come by locally. Paul's mom and his cousins grew up on the family farm. Two hundred acres of integrated production: cows, pigs, chickens, goats, dogs, cats, crops, and gardens. The farm was sold a few years ago. No one in the next generation was interested in making a go of it.

So, that's what those underground waste bins were for in Boston! Here my partner and I throw our food scraps into the front and back gardens where they are either enjoyed by the abundant local wildlife or simply break down and become soil. Vermont technically banned food scraps from home trash pickup, although we have a commercial dumpster, as do many homes in Vermont. So technically we could still toss our food scraps in the trash. We just choose not to. Returning the scraps to the earth a little at a time like we do is just natural. But using food scraps as feed for local farm animals is so much better. I like that there are companies which appear to be using food waste productively but it's likely nowhere as good as they make it sound. Just as you suggested. Great article as always.