The Invention and Collapse of Modern Retail

A nearly 200 year history of American retail, the woman who practically ran Hartford, and how Mystery Bins ties into her legacy

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

Gerson Fox was an immigrant from Germany who began his retailing career peddling household goods door-to-door in Connecticut in the mid-1800s. He would go on to found the nation’s largest privately held department store, one that, unless you’re of a certain age and from a certain part of New England, you’ve likely never heard of. I only became aware of this store by chance recently, but its history is very interesting.

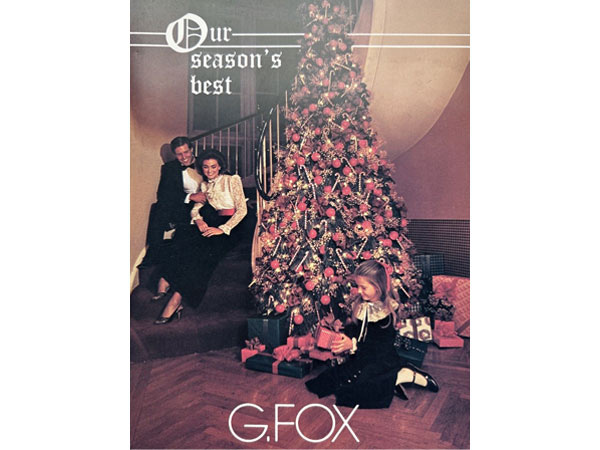

Today, I wanted to explore the story of G. Fox department store, a once-regional powerhouse in Hartford that closed its doors in 1993. In particular, I want to focus on the recent transformation of one of its suburban locations in Holyoke, MA into a liquidator, focused on selling Amazon returns and other overstock.

This story spans nearly 200 years, shows the ever changing face of how we sell and consume merchandise in this country, and also touches on issues of feminism, Jewish leadership, Black rights, and even suburbanization. Let’s take a trip back to the glory days of G. Fox department store so that we can arrive back at our present moment of overconsumption.

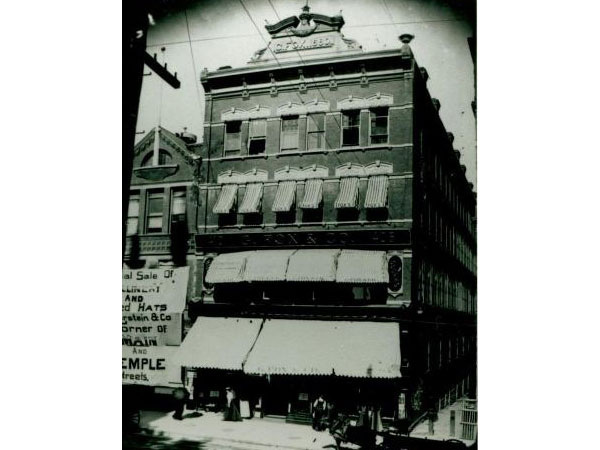

After doing well as a door-to-door peddler, in 1847, Gerson Fox and his brother Isaac opened a storefront in Hartford. According to Connecticut History, the store dealt in “fancy goods”:

“Fancy goods consisted of such things as buttons, ribbon, silk, and thread—items the Fox brothers supplemented by selling gloves, parasols, and handkerchiefs. They soon developed a reputation for outstanding customer service, even starting a home delivery service by carrying goods to people’s homes using a series of wheelbarrows.”

Gerson took over the business entirely in 1848, naming it G. Fox. In 1880 after Gerson’s death, his son Moses took over the business and built a four-story building on Main Street in Hartford. The building burned to the ground in 1917 in a fire.

After the fire, the community rallied around G. Fox and they rebuilt bigger and better than ever, with an 11-story stone building with a half million square feet of selling space.

Moses’s daughter Beatrice Fox Auerbach became involved with the family business, taking over as president when her father died in 1938, and she is one of the central characters of today’s story. It was under Auberbach’s leadership that G. Fox went from one of several regional department stores to a local powerhouse. According to the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame:

“Some of her forward-looking innovations included free delivery service, a toll-free telephone order department and fully automated billing. These advancements helped G. Fox to become one of New England’s largest and most successful department stores and the largest privately-held store in the country.”

Here are some of the other customer-focused initiatives that Auerbach implemented which made shopping at G. Fox unlike other retailers:

“While many department stores succumbed to the financial pressures of the Great Depression, G. Fox spent money upgrading its facilities, adding such amenities as air conditioning and elevators that stopped on every floor. Beatrice focused on providing customers, particularly women, with the opportunity to turn shopping into a day-long social experience. The store included a post office, beauty salon, restaurants, and a tea room. In addition, G. Fox offered the assistance of personal shoppers and even provided interpreters for those more comfortable speaking other languages.”

As a successful, single, Jewish woman running a major department store, Auerbach was likely the inspiration for the character Rachel Menken, the president of the fictitious Menken’s Department Store on the TV series Mad Men. (Auerbach’s husband died in 1927 and she never remarried.)

Auerbach also introduced many employee benefits:

“In addition to the five-day, 40-hour work week, Auerbach introduced medical and non-profit lunch facilities and interest-free loans for employees in the event of a crisis.”

And according to the Jewish Women’s Archive:

“Beginning in 1942, G. Fox hired African Americans for sales and executive track positions.”

Her fair treatment of Black employees was unusual at the time, and it earned her an NAACP award in 1958.

By the 1950s and 1960s, downtown shopping was dying and new suburbs were sprouting up all across America. Policies like the G.I. Bill allowed returning military members (almost exclusively white) to benefit from low cost housing loans and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 established the Interstate Highway system. These policies caused many white residents to flee urban neighborhoods for car-dependent suburbs.

Some retailers like Sears began to open locations in these new suburbs. But Auerbach insisted on making her downtown location a destination that could cater to a suburban crowd, whether remotely or in-person:

“It helped reach customers outside the city by operating the largest telephone ordering system in New England. It also tried to attract suburban customers into the city by expanding the store’s available parking. A five-million-dollar expansion in 1953 continued this trend, providing the store with its first parking garage. Six years later, the store doubled in size to one million square feet.”

Auerbach was also a political force in the community, and it’s said that the location of exits where Interstates 84 and 91 meet in Hartford were dictated by Auerbach to meet the needs of her store:

“There has long been speculation that Beatrice Fox Auerbach, wealthy owner of the G Fox & Co department store in the late 20th century, used her political clout to influence the construction of the interchange to create a layout in which the exit ramps would lead directly to parking for her department store. She did have the influence to do so. Auerbach was a bishop in the community, widely respected by community leaders and citizens alike.”

Auerbach sold G. Fox to The May Company in 1965, ending her family’s nearly 130 years of control of the chain. The name survived and expanded. New locations opened in Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, and Massachusetts.

In 1979, the location at the Holyoke Mall in Holyoke, MA opened as one of the major retail anchors. It was a two story shop located directly above the food court at the center of the mall. I’ll return to this location in a moment.

G. Fox closed its downtown Hartford store in 1993, and at that time, May Company decided to retire the name. The satellite locations (including Holyoke) were folded under the banner of Filene’s, the department store that I’ve written about often which started in Downtown Boston in 1890.

The Hartford location was redeveloped in 2002 into a mixed use project which included retail and office space. Today, it is home to Capital Community College.

As for Filene’s nameplate, it was retired in 2005 when Federated Department Stores (the parent company of Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s) acquired The May Company. While May Company had retained regional names and identities (including Filene’s, Marshall Field’s, and Kaufmann’s), under Federated, stores nationally were rebranded to Macy’s.

The former G. Fox location at the Holyoke Mall was subdivided (Filene’s had moved to a new location when the mall expanded in 1995).

In 1999, the upper floor of the former G. Fox opened as a Target. The lower level at one time housed an H&M, but that space became the first Hobby Lobby to open in Massachusetts in 2013.

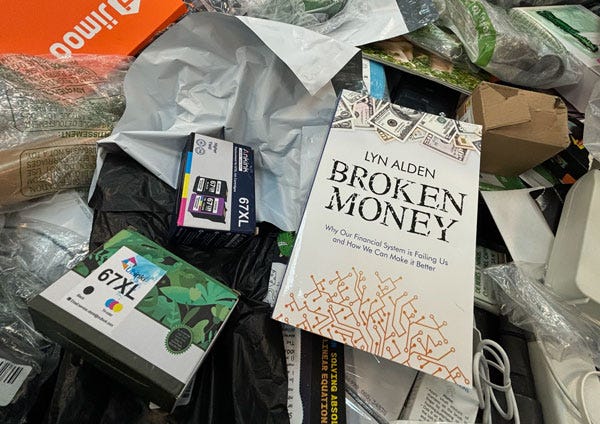

In September of this year, another section of the lower level of G. Fox opened adjacent to Hobby Lobby. Mystery Bins is a liquidator with at least one other location in New York. They specialize in reselling items that have been returned to major retailers like Amazon, Target, and Walmart.

I visited a smaller version of this type of store in Pennsylvania a few weeks ago, but as you might imagine for a store occupying part of a former department store, Mystery Bins is much larger and stocked with way more merchandise.

At the center of the store are dozens of large tables filled with a random assortment of items, some in shipping boxes, some loose. The tables are restocked with fresh merchandise on Friday nights, and when the doors to the store open on Saturday morning, every item in the bins is $15.

As the week progresses, the items decrease in price: $12 per item on Sunday, $8 per item on Monday, and so forth, until each item is only $1 on Friday. As you can imagine, there are some deals to be had ($15 for that stick vacuum pictured is a good price, assuming it’s in working order), while there are also some items not quite worth this price scale (books, notebooks, and cell phone cases, for example).

Beyond the bins, there are items with fixed prices that also likely require some closer inspection. I observed a shelf full of unopened Instant Pots selling for $85 each (although Walmart is selling a similar model for $79). But I also observed items that had clearly been returned to another retailer because of a defect for sale, like an inflatable two-person lounger with a tag that stated “won’t hold air.”

There are racks of clothing for $8 per item, including dozens of prom dresses.

There are car seats for about $35, furniture, and even appliances. There is also a section featuring food and medicine, with a clear warning that some of it may be expired. Caveat emptor indeed!

Visiting Mystery Bins is a disorienting experience to say the least. There are likely deals to be had for those willing to hunt, but it also seemed like a symptom of a much larger problem.

Returns to retailers totaled $743 billion last year. 39% of consumers reported returning an online purchase at least once per month. We are overproducing goods, we are overbuying goods, we are over-returning goods, and that results in stores like Mystery Bins, which sell the scraps to people willing to sort through them.

There was a time, not all that long ago, when going shopping was an event. Retailers like Beatrice Fox Auerbach of G. Fox looked for ways to elevate the experience to reach as many people as possible. She, and others like her, found the balance between providing for her customers and providing for her employees.

According to the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, when Auerbach sold her business to The May Company in 1965, she became very wealthy:

“She remained president of G. Fox until 1965, when she sold her privately-owned stock for $40 million to the May department stores. Upon selling the stock and realizing an enormous windfall, Auerbach stated, ‘One thing you can be certain of is that I won’t be spending it on yachts and horses, but for the benefit of the people.’”

Contrast this attitude to how businesses approach selling merchandise these days. As I write this, Amazon workers at seven delivery hubs are striking for better wages and working conditions. In New York, NYPD officers were called to break the strike and arrest striking workers. There are videos of hydrants flooding striking workers in the cold weather. Meanwhile, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who is worth $244 billion, is reportedly set to hold a secret wedding this week in Aspen that will cost $600 million.

Thinking about the history of G. Fox department store, the spirit that Beatrice Fox Auerbach brought to retailing, and what became of the G. Fox location in Holyoke, I can’t help but think we have a broken system that desperately needs to be changed. Until and unless we opt out of this system of overconsumption, our malls will be filled with less actual retail stores and more with liquidators trying to make a quick buck off of the cast offs of our extractive and exploitative ways.

There is much more to explore here, but for today, I think that’s enough to contemplate.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

At the Corner of Washington and Summer

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

The bin shopping is like the first world version of foragers at trash piles in third worlds.