Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

I was working in Boston for the first time last week since we officially moved to Western Massachusetts. At our old house closer to the city, I had the option of parking at a subway station and taking the train into the most congested parts of the city, but from the new house, it now makes more sense to drive the whole way and park downtown.

There are a few paid parking lots near where I work. For as long as I have been using these lots, they relied on an automated system where you swiped your credit card upon entry and then swiped it again upon exiting. Your charge depended on how long you parked and it was calculated using your credit card number rather than giving out a ticket.

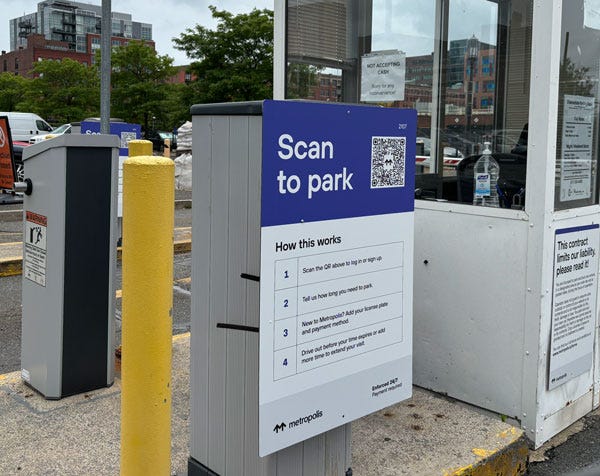

Last week though, that option was gone. The new system relies on scanning a QR code to access a payment screen on a smartphone or the use of a specialty app. In both cases, payment is tied to your license plate, which gets entered manually. (Even though the lot still includes toll booths, they are no longer staffed by humans).

Rather than require payment to enter or exit the lot, the lot functions more like a parking meter. An attendant occasionally scans the license plates in the lot. If somebody is found to have not paid, the signs in the lot say they can be booted or towed, though I’m not sure how enforced that really is.

For me, a relatively tech-savvy person with an iPhone, this method works fine, even if it’s a bit annoying to download yet another app. But as I was parking last week, I was imagining that this new system could be confusing to many people and completely inaccessible to others. I still barely know how to use QR codes.

Of course, the old system that required a credit card and didn’t even have the option of paying cash was equally inaccessible, although for some reason it didn’t feel as much so to me.

Our society and economy continually create barriers to entry based on the assumption that “everybody has a credit card” or now “everybody has a smart phone.” According to a Pew Research study from earlier this year, 97% of U.S. adults own a cellphone, with 90% owning a smartphone. But that’s still not everybody.

This has been especially on my mind as I’ve considered what life would look like without an iPhone.

I’m not quite ready to give up on a cellphone entirely, but I certainly don’t love my relationship to it. I don’t like the access that everybody has to me at all hours, through social media, texting, and email. I don’t like that I find myself distractedly checking the phone screen anytime I have an idle moment.

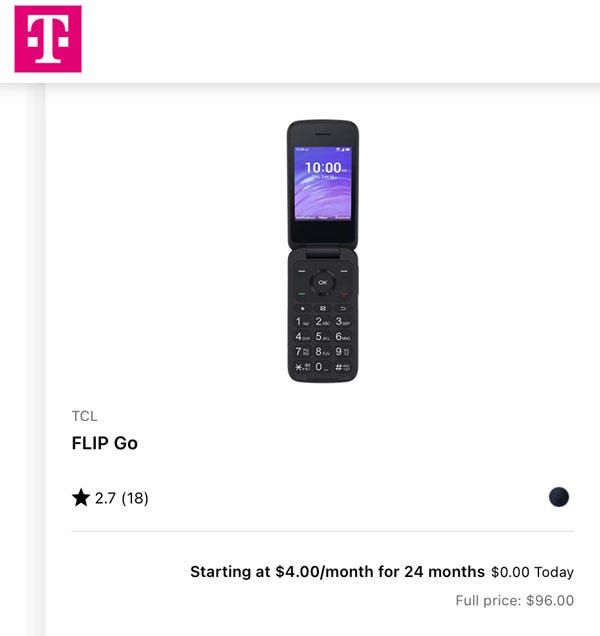

Even in this era of smartphones, cell phone companies do still sell basic phones. T-Mobile has a flip phone listed for $96, compared to the iPhone 15 which starts at $829. These are generally targeted to older people or contractors who need a durable phone on a job site. For example, here’s how T-Mobile describes the Sonic XP3Plus flip phone, which sells for $210:

“This ultra-rugged device ensures clear, crisp communication wherever and whenever work takes you, with built-for-work features that ensure the job gets done right… 100dB+ loud and clear audio speaker with noise-cancellation… When communication counts, count on the ultra-rugged, ultra-functional sonim XP3plus.”

I’ve toyed with the idea of trading in my iPhone and getting a basic phone like this instead. I would still be accessible in emergencies and could communicate as needed, but it would require deliberately sitting down at a computer to have access to the whole world. (Apparently flip phones are having a moment with Gen Z too, so perhaps I’m in the trendy bullseye here for once.)

Realistically, the idea of ditching my phone is wishful thinking and impractical. For as much as I dislike my addiction to social media, there’s the useful realities of streaming music and podcasts in the car, navigating with the phone GPS, or always having a digital camera with me.

There can be some benefit to always having an internet-connected camera available. The murder of George Floyd at the hands of police, the current genocide in Gaza, and similar events have inspired giant movements that would not have likely happened if we only understood these events through media coverage. (Floyd’s death likely wouldn’t have even made the news, nor would the officer who committed the murder be brought to justice, were it not for the video evidence from a cell phone.)

Ultimately, I am still living with my iPhone and probably will be for the foreseeable future. It’s the price of admission into our modern consumerist society, and it’s becoming increasingly difficult to be a part of the world without one.

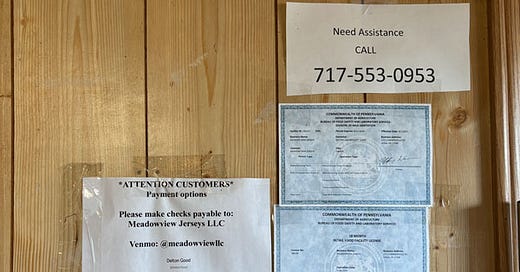

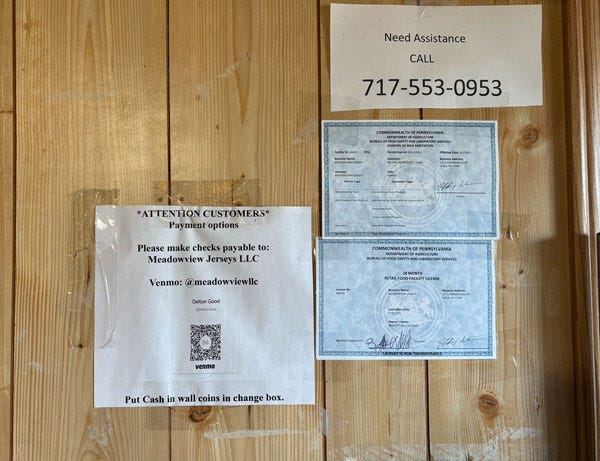

If I needed any more evidence of this, I saw it recently at an Amish dairy store we visited in the Lancaster area earlier this month.

Meadowview Dairy is a small dairy farm that raises jersey cows. Its store is a self-service shed at the end of a long driveway. It’s the kind of place you have to know about to find.

Once inside, there are refrigerated cases with raw milk, cheese, meats, and other farm products. When we first stumbled upon this place two years ago, there was also a cash box where cash was the only form of payment.

But on our recent visit, there was a new addition to this Amish owned business: a QR code to make a payment via Venmo in addition to the usual cash box. Even the Amish see access to a cell phone and online payment apps as vital to doing business now. (While the Amish don’t allow smartphones to be used in the home, some communities do allow mediated use for business purposes.)

Of course, the requirement of using cell phones or credit cards to participate in modern American society will leave some people behind. Some people can’t afford a smart phone, others may not have one for accessibility reasons, and some may simply opt to use something else for privacy or personal reasons.

The inscription on U.S. paper currency states “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private.” That is increasingly not true.

Even if most people own a smart phone at this point, I feel like using one should not be the cost of admission into American society. What do you think?

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Patient portals now digitally reveal terminal illness diagnoses. You certainly don't want to miss out on that by owning a dumb phone.

I agree with every word of this.