Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you like what you’re reading, you can sign up for a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox every Wednesday and Sunday and get my latest podcast episodes:

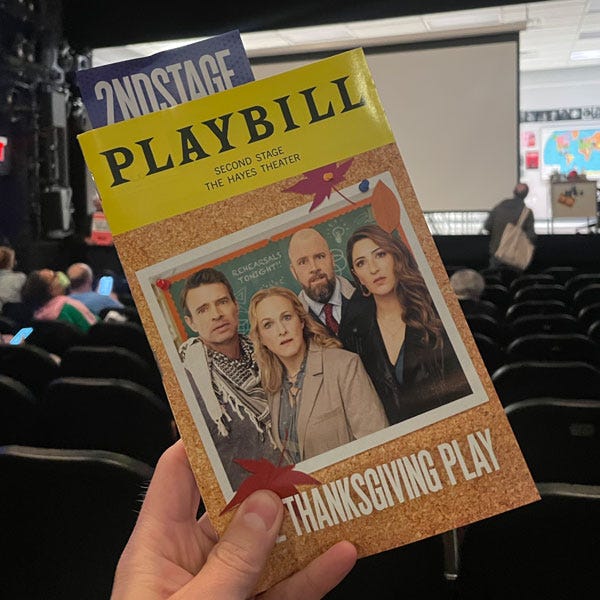

I mentioned in the newsletter a few weeks ago that Scott Foley is currently starring in The Thanksgiving Play on Broadway. My wife and I made the trip to New York last week to catch a matinee showing and were really amazed by the show, but were also left thinking about a lot of things.

I intentionally avoided reading anything about the play in advance. I didn’t want to hear the opinion of critics, the reaction of audiences, or even a simple synopsis. I wanted to experience the story in real time without any idea what might be coming.

The show was written by Larissa Fasthorse, believed to be the first Native American woman writer to have a show performed on Broadway. Starring alongside Scott is the all star cast of D’Arcy Carden, Katie Finneran, and Chris Sullivan. The story centers around four white people who are attempting to produce a culturally sensitive version of the Thanksgiving story for elementary school children.

The play is laugh out loud funny, but it balances that humor with intense moments too. I am planning to interview Fasthorse for the podcast later this summer to better understand her intentions with the show, but there were a few things that stood out to me.

For one thing, the entire play takes place on one set, made to look like a drama classroom. This setting is interesting to me because so much of our relationship to history is defined in the classroom. Teachers, textbooks, and curriculum all dictate what we actually learn and whether we are taught to think critically about the information presented or simply take it at face value. Whose narrative is that history serving?

The play intersperses live action sequences on stage with filmed songs played over a projector showing elementary age children singing about Thanksgiving. Many of the songs were sourced from teacher resource websites and they are highly offensive (one of them is set to the tune of the “12 Days of Christmas” and uses the framing of “One the first day of Thanksgiving, the natives gave to me…”).

It brought back memories of my own education, where the conquistadors and early European settlers were idolized, the contributions of Natives were rarely discussed, and we were sometimes fed downright political propaganda with little oversight. (My eighth grade history teacher wanted to make sure we all understood that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery, but was instead about states’ rights, for example).

In the play, the main characters are well intentioned, at least in their own minds. Scott’s character is chastised for eating real cheese at one point, but justifies it by claiming to be a “vegan ally.” The drama teacher (Finneran) has hired a Native American actor to perform and help consult on the script, but she later learns that this actor is vaguely ethnic enough to play lots of different cultures and has several different headshots to send out depending on the need (Carden).

Without giving too much away, despite their motives, the act of telling this story from their white perspective ends up devolving into quite the chaotic scene (let’s just say there’s a lot of theatrical blood).

The play not only shows the challenges with Thanksgiving, but it also alludes to the controversy around Columbus Day, the question of who we should be idolizing in this country, and the question of who writes our history.

These notions are fresh on my mind as we head into Memorial Day weekend and it made me think back on my experiences as a high schooler marching in the Memorial Day parade in Willoughby, Ohio.

The solemness of the day was always palpable. Our band director tried to drill into our heads how important it was that we not mess up during this performance, as we were there to honor dead soldiers, and an E in place of an E flat would be tantamount to treason in his mind.

We would start the parade in Downtown Willoughby, then march to the nearby cemetery, where a sizable group of veterans were gathered. Back then, there were still a lot of World War II vets in the ranks, though they seemed to dwindle a bit each year. We would play “The Star Spangled Banner” and a lone trumpet player was selected to play “Taps.” The veterans would often get a little weepy remembering their fallen comrades who had been gone at this point for more years than they were alive.

At the time, I too would get a little misty.

But this was also a pre-9/11 world, or more specifically, a pre-War on Terror World. Within a few years of graduating high school, we would be reminded at every turn to “support our troops” in a way that felt more like a threat than a duty. Those who dared speak out about any aspect of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were considered traitors. The Chicks, one of the largest music acts at the time, were vilified for stating that they were against the war in 2003 and were “ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas."

Of course, I knew that hippies and other college students had spoken out about the Vietnam War a generation earlier, but the message seemed clear that now was not the time for dissent. To “protect our freedoms” we needed to invade two countries, at least partially to retaliate for a terrorist attack, but also because one of those countries seemed to have “weapons of mass destruction.” (Weapons that never materialized in Iraq but that we have possessed for a long time in the U.S.)

The war would drag on for nearly 20 more years, only officially being declared over in 2021. Some of the newest military recruits serving in that war were born after it had started.

President Eisenhower warned at the end of his presidency of the dangers of the “military-industrial complex.” That short phrase has become well-known, but I think it’s worth excerpting a larger passage of the speech here as well:

“Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peace time, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United State corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.“

These words were spoken in 1961, and today, the U.S. contributes to nearly 40% of all military spending around the world. 40%. From a single country. Our spending is more than the spending of the next ten biggest spenders combined!

As I question the validity of Memorial Day, I am not saying that we should not honor the deceased among us, nor am I against any individual soldiers. Both of my grandfathers served in the Navy and the personal reasons for enlisting are numerous.

My bigger concern is how we lionize the military as an organization to the point that it’s beyond question or scrutiny. When I think back on Eisenhower, I wonder who this is benefiting? Flying a flag to remember a deceased relative is one matter. Covering your entire driveway in hundreds of flags, ending with a giant light up flag at the end is another matter entirely (I witnessed this at the Cabela’s store in Hartford on Friday but neglected to take a photo.)

Should we really have such a large defense apparatus when there are people in this country that cannot afford to eat or cannot afford health care? Should we glorify an industry that treats American (and “enemy”) lives as expendable, while protecting and safeguarding the most powerful and influential among us (including the President and generals)?

Or if this holiday is going to exist, maybe it shouldn’t be a time for cookouts and mattress sales. Maybe it should be more solemn, a time to honor the families that lost a loved one and to sit with them in that grief. The loss of a soldier is a tragedy, but the loss of one to support an economic machine makes that loss much, much worse.

Much like The Thanksgiving Play, this is a difficult topic to broach, in part because our attitudes and assumptions about it have been formed early in school and are reinforced constantly in popular culture. Every morning through my school career, we stood and faced the flag and recited the Pledge of Allegiance. Even valid criticism is often seen as the antithesis of allegiance.

I don’t have an answer yet, but after seeing the play, I don’t know that I can continue to celebrate traditional American holidays without at least being a little more critical and considering whose version of this holiday I am celebrating and why.

The Thanksgiving Play is showing at the Helen Hayes Theatre through June 11. Click here for tickets and more information.

What are your thoughts? I’d love to hear from you in the comments!

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.