The Urban Planning of Disney

What the Vacation Kingdom can teach us about cities, suburbs, density, and transit.

Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

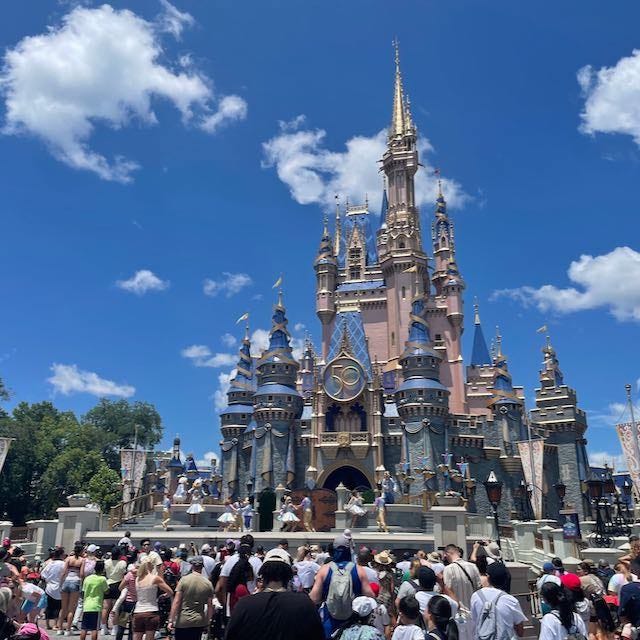

As I mentioned on Wednesday, we are just getting home from a trip to Walt Disney World in Florida. We camped in our RV for a few days, but we also spent some nights in Disney owned hotels.

I have been vacationing in Florida for many years and have often thought about how the urban planning of Walt Disney World can influence the way that we design, build, and live in our cities. Since it’s fresh on my mind, I thought it was worth exploring that idea today.

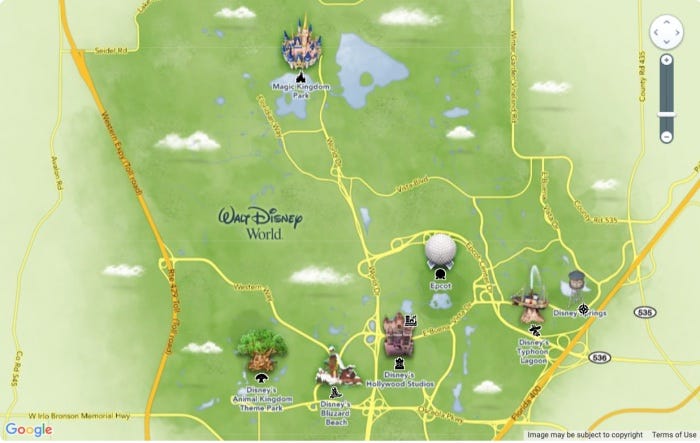

For the uninitiated, Walt Disney World is massive. It’s a city unto itself, twice the size of Manhattan in land area. Within its boundaries are four theme parks, two water parks, and more than thirty resort hotels owned and managed by Disney (plus several run by third parties). There are also water treatment plants, electrical generating facilities, large solar photovoltaic installations, and lots of logistical support buildings that deal in everything from construction to laundry.

Walt Disney acquired the 43 square miles of land in the early 1960s using shell companies to keep the purchase a secret. His hopes for the Florida property were much bigger than just an East Coast replica of the amusement park he was already operating in California; he planned an entire city that would showcase futuristic technology and advances in urbanization.

Walt Disney did not live to see the resort’s opening in 1971 (he died of lung cancer in 1966), but weeks before he passed, he made a film about his plans for Florida:

In the film, Walt imagined a pedestrian-friendly city with dense housing, shopping, and workplaces in the center. Radiating out from that core would be housing of lower density, green space, and schools. Mass transit would exist in the form of monorails for long trips and “people mover” trains for local traffic. Automobiles would exist, but much of the traffic would be buried in underground tunnels.

In 1966, suburban housing developments, the interstate highway, and car dominance were all trendy, yet Walt was imagining a future that sounds more like Amsterdam than America.

After Walt’s death, plans for the Florida site were altered significantly and have evolved over the last five decades. But traveling to Walt Disney World still presents some of the core tenets of that original vision.

The entire network of hotels, parks, and other attractions are interconnected through mass transit systems: buses, monorails, boats, and gondolas.

My first time riding a mass transit bus was as a teenager on a visit here, and it inspired me to begin riding the bus in my hometown before I had my driver’s license. I was able to reach the mall, the beach, and many more places near where I lived because I learned how buses work on vacation at Disney.

There’s also the ability to walk to many places to get around, depending on the hotel. This was especially important when we had young kids in strollers. We used to prioritize a vacation around the ability to walk, as it’s not an easy thing to do in our suburban neighborhood. It was a good feeling to visit a theme park and walk back to the room for a midday rest.

However, Disney is not hostile to cars. We have rented cars many times and found the roads to be easy to navigate and the parking to be plentiful. Arriving in a 32 foot RV at the entrance to luxury hotels this week, we were welcomed with a smile and a wave, and in some cases, directed to special RV parking that had been set aside for folks like us.

The big difference between driving at Disney and driving in suburbia is that the auto infrastructure is largely invisible to those not using it. Parking is vast, but largely hidden. Cars have their dedicated space, and people have theirs. After leaving the parking lot, there is no need to look both ways in traffic or worry that a stray car might pass.

A stay at Disney is transit agnostic- there is no “perfect” way to get from one place to another, just lots of options.

Beyond the transit, Disney has shown some interesting patterns of development lately that I think could hold lessons for how we reshape our cities and suburbs.

The early hotels on site were relatively compact and built near the theme parks, but beginning in 1988 with the opening of Caribbean Beach Resort, Disney started building a very different style of hotel. They were spread out across massive properties and were lower density. Caribbean Beach, for example, had 33 buildings with guest rooms, but each was only two stories tall.

Resorts of this era and built in this style remind me of suburban neighborhoods. Because they were so spread out, it could often be a long walk to get to any services like the front desk, restaurant, or pool. Some of these resorts are so spread out that using a bus is the only practical option to get to a desired destination.

Lately, however, Disney has shifted from building in a suburban sprawl model to building in a more compact, dense style. We stayed in the newest resort on this trip, which is called Riviera Resort. It was built over a section of Caribbean Beach that was demolished.

Replacing spread out, two-story buildings is a single 10-story building. By building up instead of out, all rooms are a short elevator ride away from services like dining and swimming.

While the buildings that were once part of Caribbean Beach may have had more trees or other greenery surrounding them, Riviera makes smarter use of green space, with a central plaza space designed for walking, people watching, running, and playing lawn games.

Riviera Resort showed me that replacing sprawl with density is possible and that the results can be better in the end. Part of the appeal of a suburban home is a large green lawn, but Riviera shows that the lawn can belong in the public realm and still be just as functional, or arguably, more so.

Denser buildings are coming to traditional suburbs. The housing shortage, which I wrote about last week, has caused some sprawling suburbs to embrace more urban forms, including mixed-use developments where retail and restaurants occupy a ground floor and apartments or office space are above.

Yet there’s one other lesson that I learned from Riviera this week that applies equally to the suburbs: density and good transit need to go hand in hand. Apartments that are accessible to services and allow for some walking is preferable to apartments surrounded by a sea of asphalt parking and no services, but in many cases, they still require a car for getting out beyond their small development.

Disney added a new transportation option as part of Riviera’s construction. It’s a continuously running gondola system known as The Skyliner that connects Riviera, Caribbean Beach, and a few other resort hotels to Epcot and Disney’s Hollywood Studios.

Unlike waiting for a subway or monorail, which loads lots of passengers in infrequent trains, another gondola is always ready to be loaded with small groupings of passengers. This means there is virtually no wait. They are electrically powered and are nearly silent to operate.

They also add a nice kinetic energy to the area. We enjoyed eating lunch at Riviera at a table alongside a small lake, watching the colorful gondola cars glide overhead.

Some of the lessons that I took away from Disney this week are more theoretical than practical. After all, it’s easy to decide to tear down a section of an old resort and replace it with higher density when one company is the sole landowner. That becomes much harder in the real world, where private ownership rights usually trump the public good.

Still, changes to the built environment happen in our communities everyday and there’s no reason to think that the status quo of car accessible and pedestrian unfriendly development needs to continue to be the default.

In my own town, there’s debate about how to redevelop a large corporate campus that no longer has a tenant. A mixed use area seems to be in the early planning stages, where residential and retail will be combined. There are examples where this is done smartly and improves quality of life for everybody, and there are haphazard versions where the result is net negative.

Some of the key takeaways from this trip that I would like to see implemented at home include the idea that density can be good, if smart green space is integrated. Transportation infrastructure should be accessible to cars, pedestrians, bikes, and mass transit, perhaps with their own separate uses. Services must also be accessible and useful. Living near retail is more helpful as a grocery store or hardware store than a gift shop or clothing boutique.

Walt Disney hoped to make his land in Florida a test case for the future of cities. I walked away with several lessons this week, and I hope those in a position of influence in our neighborhoods also take some lessons, good and bad, from what Disney has built over the last 50 years.

Related Reading

Where Can I Get a Good Burger?

Did I Have West Virginia Wrong?

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Please consider sharing this with a friend that you think might enjoy it, or better yet, share it on social media so you can tell hundreds of friends!

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath