Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

The top-performing movie of 2023 was Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, grossing more than one billion dollars world-wide. There is perhaps no story better suited for our times: a woman made of plastic, who lives in a plastic house, drives a plastic car, and has a plastic boyfriend.

Plastics have a long history in cinema.

In The Graduate, 56 years prior to Barbie, Mr. McGuire gives some career advice to Benjamin Braddock: “There's a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?”

21 years before The Graduate (and 77 years before Barbie), Sam Wainwright offered to let George Bailey in on a business idea in It’s a Wonderful Life:

“I have a big deal coming up that's going to make us all rich. George, you remember that night in Martini's bar when you told me you read someplace about making plastics out of soybeans?… Well, Dad's snapped up the idea. He's going to build a factory outside of Rochester. How do you like that?”

The next time we see Sam Wainwright, he’s being driven by a chauffeur in a fancy car, his wife draped in a fur scarf. At the end of the film, he sends a telegram authorizing a transfer of money to George Bailey worth up to $25,000, the equivalent of $433,000 in today’s money. Plastics did very well for Sam Wainwright!

Art and cinema reflect who we are as a people. And, to quote the 1990s band Aqua, we are increasing becoming “a Barbie girl, in a Barbie world.”

Historians define time based on the prominent technology: there was the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age. We may not acknowledge it enough or even realize it, but we are firmly in the Plastic Age now.

In the film Barbie, Barbie and all of her friends live in plastic “dream houses.” We think of the homes as caricatures, as exaggerations.

Air BnB built a real-life house in Massachusetts last year based on Barbie’s Mattel counterpart Polly Pocket. The compact house (that literally resembles a makeup compact) is in the spirit of the Barbie sets, but also looks kind of ridiculous in a real-world setting. The prop makes for an interesting photo opportunity, but the house is completely non-functional for any of the things one would expect from a home. For one thing, the compact lid doesn’t close, leaving the setup exposed to the elements (but it’s all plastic, so maybe that’s not a concern).

There’s also no bedrooms. The few people who won a lottery to “stay” at the property slept in a tent adjacent to the large prop, because it wasn’t really designed as a home.

We see Barbie’s house or Polly Pocket’s house as bizarre abstractions, but our own houses are becoming increasingly plastic.

My wife and I are in the middle of a kitchen renovation, and choosing a countertop material has been difficult. We ended up purchasing quartz counters, which are made up of about 94% powdered quartz (a mineral) and 6% polyester resins (plastic). The abundance of natural quartz, and the fact that it could be extracted and used in parts rather than relying on a whole slab (like a natural stone), helped ease my mind some, but no countertops are perfect choices.

I had also investigated wood countertops from a local supplier, but in order to make their wood surfaces more durable, the fabricator coats the wood in epoxy and polyurethane. It may look like wood, but it’s become plastic. Corian, laminate, and many other conventional countertop materials all contain large amounts of plastic too.

Natural stone does not, but we opted not to go that route partially for maintenance and partially because something has never sat right with me about pulling a piece of stone out of the earth that has been there for thousands of years, only to use it for 15-20 years before discarding it again.

But the plastic in our homes goes far beyond just the content of our countertops.

We are working with a contractor right now on plans to rebuild a sun room on our house. With every decision comes more plastic: do we want vinyl windows or wood? Well, the room has a hot tub from the old owner and gets humid. Vinyl will hold up better.

For the trim, do we want wood, which will have to be repainted every few years, or Azek, a cellular PVC? Vinyl or wood siding? Wood or composite decking?

At every turn, we are choosing the convenience of less maintenance over using real, organic products. I don’t love it.

I feel guilty thinking about the health of the people that manufactured all that plastic and the contractor who has to install it. Every time he cuts that material with his saw, little bits of plastic will become airborne and could land in his lungs. I can only hope he’s wearing a mask.

Those plastic pieces which don’t get inhaled will fall to the ground and become a part of our soil. What’s the long term toll of that?

It may seem like Barbie’s house is a fantasy set from a movie, but my own house shares a lot with hers. My house is not as pink, but it’s every bit as plastic.

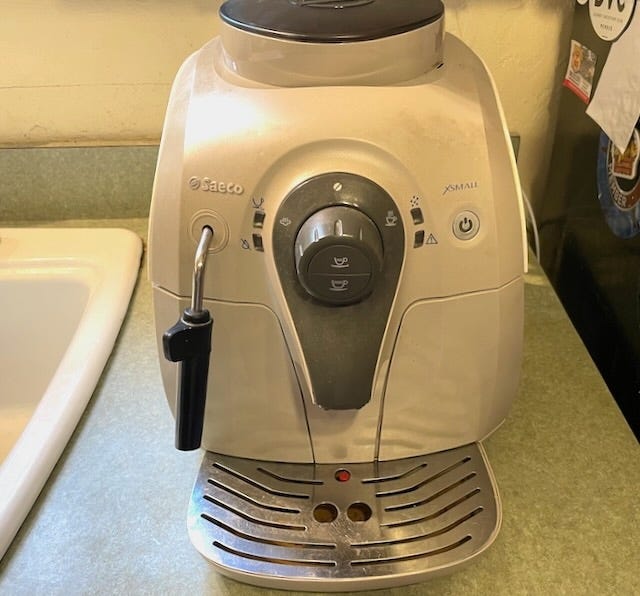

Nearly a decade ago, I bought a nice, European-style countertop espresso machine. I’ve written about that machine before. I liked that it ground beans freshly for each cup, then made either an espresso shot or an 8 ounce cup right on the spot. I loved that coffee machine, until one day I didn’t.

I was filling the water reservoir at the kitchen sink and realized it was plastic. Then I thought about the other components of the machine, which I had taken out for periodic repairs and cleanings. All plastic.

I may have been buying the best fair trade, organic coffee beans, hoping to avoid toxins, but I was processing them through hot water and plastic every single day. Of course, most drip coffee makers are no better. And Keurig machines not only have plastic parts, but the coffee grounds themselves are literally encased in plastic, through which steaming hot liquid is forced to brew a cup. Gross.

I began to research insulated French presses, as the ones with glass walls turned cold too quickly for me. I found that Stanley makes a large, stainless steel version that supposedly kept coffee warm for hours. Stanley insulated thermoses were first patented in 1912 by William Stanley of Great Barrington, MA and for several years were manufactured in the Berkshires. These days, their products are all manufactured in China. I wasn’t crazy about buying a brand new one, especially as Stanley has come to symbolize overconsumption, but I was able to find a used one on eBay. My morning coffees now come with slightly less plastic.

You might think it’s a bit neurotic to focus so heavily on avoiding plastic, but according to one study, “Americans eat and drink an estimated 39,000 to 52,000 microplastic particles every year, depending on age and sex. Those numbers jumped to 74,000 to 121,000 when scientists included inhalation of microplastics.”

While the effects of ingesting all of this plastic is unknown, I think it’s fair to assume that it’s probably not ideal and should be avoided if at all possible.

Our drinking water is also contaminated with plastics. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, known more commonly as PFAS, are synthetic chemicals that are have been used in everything from cookware to packaging to stain resistant coatings since the 1950s. PFAS are now being discovered in drinking water in large quantities.

Our drinking water also contains microplastics, with higher quantities in bottled water than in tap water.

Many people know this and filter water to make it safer. But take a look at the water filters offered for sale at any home improvement store and you’ll notice something. Whether it’s a pitcher-style Brita filter, an under sink water filter, or a whole-house filter that cleans everything entering the home, they’re nearly all made of plastic and use plastic as a means of filtration.

If we want to avoid drinking the plastics in our water, we have to filter that water using a plastic filter. It literally makes no sense.

For many years now, I’ve been sourcing most of my food either directly from farms or from small, local grocers that deal directly with farmers. Because of this, I am in a bit of a bubble relative to how the rest of the world eats.

That bubble was broken on a recent visit to Trader Joe’s. I couldn’t believe what the produce aisle looked like!

I know Trader Joe’s is known for snack foods, frozen foods, and other packaged goods, but the produce aisle looked like a wall of plastic wrap that could have been any of those other departments.

Contrast that view with what I see at my local farm stand in the summer. Leafy greens freshly cut from the roots. Carrots and radishes dug from the ground, some residual soil still clinging to the sides.

We are so desensitized to plastic and so disconnected with where our food comes from that we have normalized the “enplastification” of the produce aisle.

Our relationship with plastics extends to the fabrics on our backs too. For thousands of years, humans have clothed themselves in materials from the natural world: cotton, hemp, silk, wool, leather. But that started to change with the introduction of synthetic fabrics made from, you guessed it, plastics.

Take a look at the labels in your closet and you will begin to notice plastics under many names: polyester, nylon, acrylic. These fabrics are cheap to produce and are part of the reason for the explosion in “fast fashion.”

Ironically, the more our clothing has become considered disposable, the more we are crafting it with materials designed to last several lifetimes that takes decades or even centuries to biodegrade. An estimated 60% of clothes are now made with synthetic fibers. Every time these clothes are washed, they release microplastics into our water systems, which then enters our drinking water in the most warped version of the circle of life.

Americans discard 17 million tons of clothing per year, with the majority being clothing owned less than one year.

All of that trashed clothing has become a major problem in the Global South, where countries like Chile have received millions of tons of “recyclable” clothing that now just sits out in the desert (or worse, gets set on fire to be destroyed, releasing toxic chemicals to the air). I talked about this on my podcast episode with Francisca Gajardo, a Chilean fashion designer who knows these clothing dumps well. If you’re interested in learning more, that interview is worth a listen.

While the real world around us becomes increasingly synthetic, the virtual world is also becoming more “plastic,” at least metaphorically. AI artwork and videos are taking over social media feeds. It’s not even possible to perform a simple Google search without receiving AI answers.

I recently saw a job recruiter on LinkedIn post their frustration with candidates using AI software like ChatGPT to answer mundane application questions like “Why do you want to work at our company?” I can’t find that post now, but the comments were pretty unanimous: candidates will stop using AI to answer job questions when companies stop using AI to screen resumes.

The hiring process is no longer about human connection; it’s simply AI prompts talking to each other and screening people until keyword matches are found. Applicants use AI to tweak their resumes, AI reads those resumes, and a human only intervenes at the very end of the process.

AI is truly taking over all of our online communication. For years, Google’s Gmail has offered suggestions in real time while emails are being composed and even suggests short responses to emails like “Sounds great” or “Got it.”

These auto-responses now populate our messaging apps and writing apps too. I recently upgraded the operating system on my MacBook and was shocked to see predictive text being used anytime I tried to type anything. I had to search how to turn it off, because I don’t want a machine dictating my thoughts. (If you’d like to know how, follow this tutorial.)

Digital communication, once a means to connect us to other people across great distance has now become machines talking to machines. Synthetic communication. Plastic.

I’ve been reading a book by architect Jonathan Hale published in 1994 called The Old Way of Seeing. Hale argues that up until about 1830, all buildings throughout the world were designed by humans using natural ratios. The same ratios that make up a human face or a maple tree were present in our homes, our cities, and our churches, and this was found in England, Mexico, Japan, Italy, and many other places.

Hale believes that these patterns for seeing were not something that was taught, but rather were just intuitively understood as a function of being human and being in touch with nature.

Around 1830, at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, people began to lose this skill and architecture began to focus more on decoration and ornamentation than on true design or pattern. As Hale wrote in 1994:

“Before the machine age, no one had to make the choice to be conscious of pattern, to be aesthetic. Now, to be in visual touch requires taking a deliberate step. Numbness is today offered all around. We fall into it easily. We do have to choose to be awake, as people in the past did not.”

We are numb. We are plastic.

To close out, I want to quote from an essay originally published in 1969 in the magazine Education as an Art. It’s by Ernst Katz, describing how people function in the machine age:

“The senses become dulled, the person becomes inattentive, restless, and nervous. He finds it more and more difficult to concentrate, consequently he achieves little, yet he never has time nor interest for undertaking anything. He may become apathetic, and often develops circulatory or heart trouble after a while. Teachers with some experience in these matters can easily tell the TV addicts from those who do not watch TV habitually, by their different attention in class. The 'hectic' pace of life that kills so many adult hearts is not hectic because so much bodily activity is required but because so much immobility, coupled with sensory overload, is imposed upon us.”

Katz, writing around the same time that The Graduate was released in theaters, was describing a world with over-the-air television with three networks. He couldn’t yet imagine home computers, video games, social media, or any of the other electronic stimuli we now can access in our pockets.

There is a lot more to say on this topic, from the Botox we inject into our faces to the synthetic chemicals we spray on our lawns, but this feels like a good place to leave this discussion for today.

I opened this essay talking about Barbie. Many people claim they liked that movie for its feminist messages. But I wonder if at least some of the reasons for that film’s success come from the fact that viewers saw their own plastic lives reflected on screen?

We are firmly in the Plastic Age now and are increasingly becoming plastic people. What that means for the future of humanity is anyone’s guess. I can’t avoid plastic entirely, but for my part, I want to be conscious of what plastic is doing to me and to all of us.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

Swanky Swigs and Jelly Glasses

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

This is a necessary and depressingly overwhelming analysis, but thank you Heath! I literally had those same thoughts about the plastic water filter and my coffee maker this week.

I have been drinking out of plastic biking bottles for cycling and swim FOR DECADES so that's horrible. I see many fellow swimmers have lately switched to heavy clanging metal water bottles for the pool.

I have to laugh a little that it's actually a break from thinking about macro, end of empire, democracy-crumbling problems to focus on the micro, chronic, everyday ways we are continuously destroying our bodies and environment. Oy.

Onward. Solidarity. ❤️🔥