Where Did Gravity Go?

Exploring a lost way of life in a rural Iowa town

Welcome to the Quarantine Creatives newsletter, a companion to my podcast of the same name, which explores creativity, art, and big ideas as we continue to live through this pandemic.

If you like what you’re reading, you can subscribe for free to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox on Wednesdays and Sundays:

The Twitter account @everylot_usps shares Google Street View images of random post offices around the U.S. Last week, it posted an image of the post office in Gravity, Iowa. When I first encountered this tweet, I could not anticipate the journey I was about to take through a town I had never heard of. Today, I’m going to share that trip with you.

This photo immediately sparked my curiosity for a number of reasons. This post office building is quite slim for a standalone structure. It feels like it was once part of a larger block of buildings, presumably that had been demolished at some point. It reminds me of the “ghost buildings” that

has written about, where an adjacent building is demolished and what was once an interior party wall becomes exposed as an exterior wall.When I started to investigate the Gravity post office closer, I learned that the side of the building features a mural with the town name.

Rural post offices are often little more than small wooden or concrete block structures, but this one feels like it was part of something greater. I had to learn more!

On a whim, I decided to call Charles Ambrose to chat more about Gravity. He serves as the mayor of the town and also owns Garden Charlie’s, a greenhouse and nursery business. As a resident for 68 years, I was hopeful that he could tell me more about what once was.

I first wanted to know more about that post office building. Was there once something else that stood next to it?

“There was a woodworking shop in there at one time.”

My suspicions were correct. The post office was part of a larger block of buildings. Or at least, it used to be.

“Now the post office is gone. They knocked it down in the spring. It was condemned. The walls were falling out.”

I became a little wistful. The image of this solitary post office, the last remnant from a different time, is now but a memory. The lot at the corner of Main Street and 3rd Street is now empty.

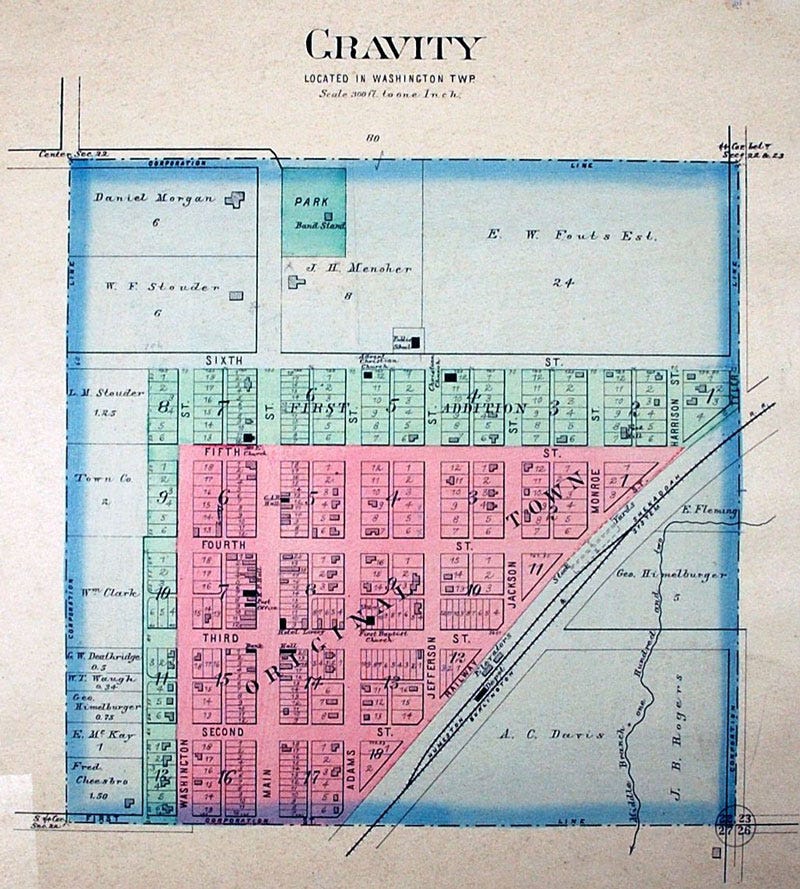

According to the 2020 census, the population of Gravity is about 150 people. It sits in the southwest corner of Iowa, roughly a two hour drive from Des Moines, Omaha, or Kansas City. When taking a tour of the town on Google Street View, there isn’t much to see anymore.

Still, the few buildings that are still standing have a certain grandeur to them, even if they’re in a similar state of disrepair to that old post office.

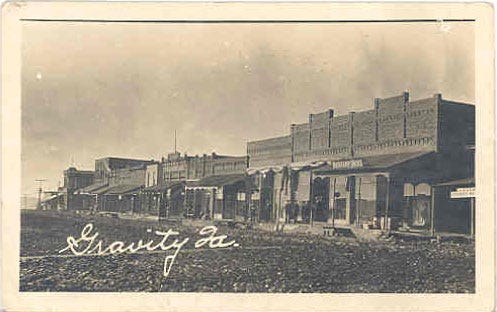

In fact, these few remaining buildings were part of a bigger commercial district. Here’s what the Main Street of Gravity, Iowa looked like in an undated photo, likely from the early 1900s. I believe that’s the post office building at the far left of this image:

Mayor Ambrose painted a picture for me of how he remembers the town in his childhood during the late 1950s:

“I could tell you from when I started to grade school in town, there was two grocery stores, a hardware store, a barbershop, three filling stations, a big lumberyard, two restaurants, a hardware store, and all that's gone.”

That’s not to say that Gravity was ever the busiest or most happening place. The population was always quite small compared to larger cities. At its peak in 1900, there were about 500 people in the town, and that population stayed relatively steady through the 1940s. The railroad, which once ran through town, left after World War II, and the population has declined steadily through all of Ambrose’s life:

“I can remember in the late fifties and early sixties, the town just decreased in size, it seemed like every year”

The story of population decline in Gravity is not just a story of the town, but a story of the nearby farms as well. As Ambrose tells it:

“Used to be when I was younger, there was a farm on about every 40 or 80 acres, and now a lot of the farms are over 10,000 acres. So there's not near the number of rural people. All the little towns in this part of the state anyway were based on the agricultural business that come into them. And when that changed and the people left in the country, the businesses just couldn't stay in business in the little towns.”

This is a common refrain across many small towns in the U.S. As I discussed in last week’s newsletter, farming used to be a fairly closed system: waste from livestock became fertilizer for crops, those crops fed livestock, which made more waste, and on and on.

But after World War II, chemical companies began selling synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides. Technology also came to the farm, with powerful gas tractors replacing much of the work that livestock or farm workers used to perform. These new machines and chemical inputs came with added capital costs. Some farmers were able to adapt to the new ways, but many others took on large debts or even lost their farms entirely.

When a family moved off of their small farm, large agribusiness firms often purchased the land and consolidated several nearby family farmsteads into one giant operation.

But, the loss of all of those individual farm families also spelled doom for the local merchants that sold groceries, hardware, or banking products to the farmers. Not unlike how farms used to be self-sustaining little ecosystems, local economies also used to function in much the same way. Money never really came into town or left the town in big amounts; it just kind of changed hands within the population a number of times.

George Bailey explains these dynamics in the pivotal “run on the bank” scene in It’s a Wonderful Life:

“You're thinking of this place all wrong. As if I had the money back in a safe. The money's not here. Your money's in Joe's house... right next to yours. And in the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Macklin's house, and a hundred others. Why, you're lending them the money to build, and then, they're going to pay it back to you as best they can.”

When the farms left and these local shops closed, a way of life went with them. Says Ambrose:

“From the town, you could walk anywhere to the main street. You're talking about a five to six block walk, at the most.”

It goes back to a point that

has made many times, and which I love repeating:“The difference between what we call a ‘city,’ a ‘town,’ or a ‘village’ is entirely of degree, not of kind.”

Gravity, a town of never more than 600 people, once had a walkable Main Street where most business could be handled without needing a car. This is a lifestyle that is reserved for people in urban environments these days and is considered the trait of a big city. But living car-free was a reality only a few decades ago, even way out in the country.

Today, the nearest grocer, hospital, or service of just about any kind is about seven miles from Gravity and only accessible by car. Wal-Mart is about 20 miles away. Businesses that are considered “nearby” in this part of Iowa went from being within a five block radius on foot to a 20 mile radius by car. This pattern has repeated itself in cities, towns, and suburbs across the U.S. over the last half-century.

As the mayor, Ambrose recognizes the challenges of not having businesses and other services located right in the town:

“Usually the older people won't move into town here because we don't have a doctor, we don't have a grocery store. The elderly has to move for those services, if they don't feel like they can access it by automobile.”

I think back on some of the building blocks of a strong community that Jonathan Berk from Patronicity shared with me a while back, which included a diverse housing mix that can accommodate people at different life stages and an infrastructure that supports mobility.

Gravity of the early 1900s allowed for people of all ages to stay in the town at different life stages and to conduct their business locally. Ambrose cites the challenge of elderly people and access to healthcare, but young people also have to ride a bus to school instead of walking within the neighborhood. Middle aged folks need to leave the community to find work. A lack of local business and a lack of mobility affects everybody.

This point is made even more apparent when reading “Some Early History of Gravity,” an article by Celesta Smith originally printed in 1934 in the Gravity Independent (a long defunct local newspaper). Mrs. Smith describes some of the early merchants in town and their living arrangements:

“Stouder & Sons general merchandise store was situated a little north of where the W.F. Johnson store now stands… The building material was hauled from Bedford and the family lived in the back part of the store… Jo Faith had a general merchandise store on the east side of Main Street and continued in business for a number of years… William Mellinger also kept a store of general merchandise. His family lived in the back part of the store.”

In most places, we segregate residential and commercial uses through zoning, often restricting residential housing to detached single family structures. The notion of living above or behind a shop is thought of as something that only happens in big cities, but it was a part of small town life less than a century ago.

For Mayor Ambrose, it can be challenging to make investments in anything that will benefit the city, as the property tax base has eroded along with the population:

“The property values went down over the years. I counted one time, there was 67 houses gone that I could remember was there. They're just lots. Plus, commercially, we don't have hardly any commercial properties left. Right now, we're getting by. We're able to maintain the roads with the little bit of money we get from the state and the property tax. We're able to provide the essential services, but that's about it.”

I wish there was a way to restore some of the life and vitality to Gravity and the countless other small towns like it that once had walkable cores populated with local businesses and surrounded by farmland. But the circumstances that brought us to this point are myriad and solving for one piece does not fix all the other broken parts.

However, Gravity is an affordable place to live and Ambrose tells me that there are signs that new people are coming:

“We’ve got a couple of people that are in the process of building new homes in town, which I think is a plus.”

What Gravity, and many other small towns like it need, is somebody willing to make an investment in the community. A new coffee shop, a simple general store, or a restaurant may create enough of a spark to get others to open small businesses in town. On Schitt’s Creek, the opening of Rose Apothecary changed the face of that small town. Could there be a David Rose of Gravity?

I asked Ambrose what one business he would most like to see operating in Gravity if he were able to wave a magic wand and make that happen:

“I think what we could use the most right now is a small gas station and grocery store combination. There are a lot of those around here. You know, just to provide a minimal amount of necessities and gas. And I think that would be a a big plus for us.”

And that condemned post office that started this whole journey? The hope is that it can come back in some form to at least give residents one local place to walk to:

“Right now we're trying to get the Post Office to work with us. We'd like to put up a building to get the post office back in town. We're willing as a community to build a building to put it in, but you know, like any government, big government, they're kind of slow to work with.”

A post office can be the center of civic life, a vital connection to the outside world, and a source of local employment for residents. Under the right conditions, a new post office might also be a catalyst to further development and reinvestment in the town. As the slogan on the sign welcoming visitors to town states: “If Gravity goes, we we all go.”

As a postscript to this story, Gravity made some local headlines recently when the town was name-checked during a Super Bowl ad for Turbotax. If you’re interested, here’s that spot:

And one other postscript that’s worth mentioning, which is the loss of diversity that happens when a small town’s economy evaporates. Today, Gravity is 99.5% white, but Mayor Ambrose was proud to point out that historian Lulu Johnson hails from Gravity. She was the second African-American woman to earn a PhD in the United States, and the first to do so in the state of Iowa.

What are your thoughts? I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Related Reading

If you’d like to catch up on past episodes of the Quarantine Creatives podcast, they can be found on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Stay Safe!

Heath

I love stories like this that are evoked from a single, haunting image. Growing up in Cleveland, we didn't use a car very often. We took public transportation to downtown for shopping or walked to the local version of Walmart, it was called Zayre's. Our own neighborhood had plenty of self sustaining businesses and our neighborhood friends lived over the storefronts. Not that long ago. But also a lifetime ago.