Disney Does Inclusion

Disney's most racist film, its latest ride, and whether it will ever achieve true inclusion

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

On November 12, 1946, Walt Disney’s latest film premiered at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta. Song of the South was supposed to be Disney’s masterpiece, a crowning technical and artistic achievement. It would end up being his most racist movie and one that continues to plague Disney management to this day.

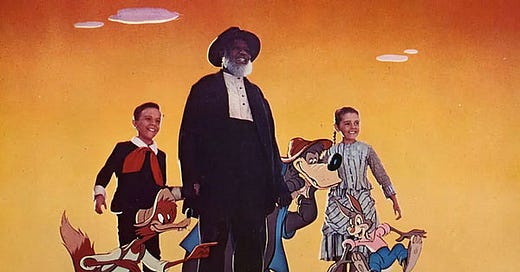

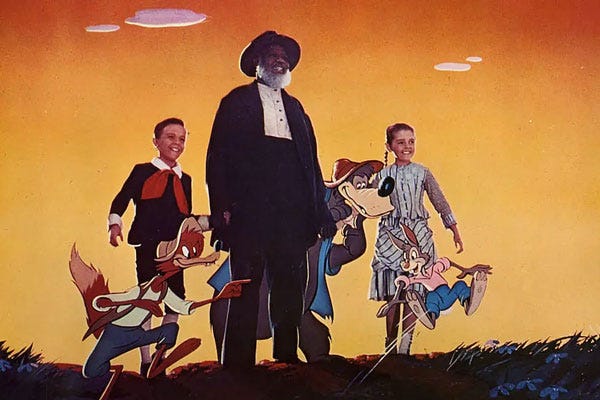

Song of the South was revolutionary for its method of combining live action actors with animated characters. Disney had been experimenting with this technique for two decades, premiering the Alice Comedies silent cartoons in 1924.

Song of the South was meant to be a culmination of everything the Disney team had learned from those early cartoons while also combining the successful formula of some of his later projects: a catchy soundtrack, brightly animated characters, and beautiful animated environments.

The film’s story is set in the days soon after the Civil War. The plot revolves around a young white boy who befriends a Black worker on his grandmother’s plantation. The man proceeds to tell the young boy the Uncle Remus stories, which were originally published by Joel Chandler Harris. Harris was a white man who worked on a Georgia plantation. He became famous for publishing the stories he heard from people enslaved on the plantation.

Song of the South earned some acclaim. Its title song “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” won an Academy Award and star James Baskett was also presented with a special Academy Award. But the film also garnered controversy from the day it premiered.

According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia:

“Walter White, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote that the film gives a “dangerously glorified picture of slavery.” The National Negro Congress declared that the film “is an insult to the Negro people because it uses offensive dialect; it portrays the Negro as a low, inferior servant; it glorifies slavery.” Ebony magazine criticized the film’s “Uncle Tom/Aunt Jemima caricature.” Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell called on New York theaters not to show it.”

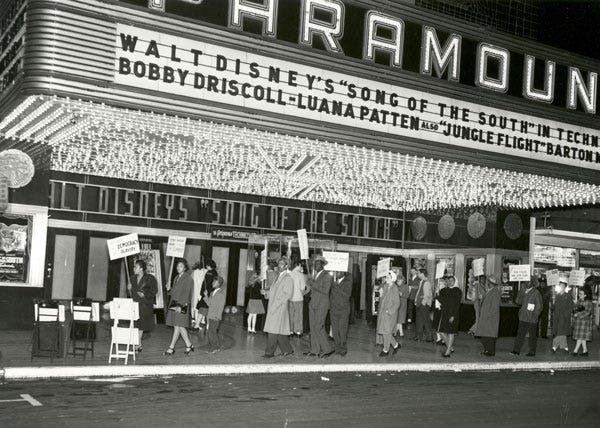

There were protests and boycotts of the film, but they weren’t enough to prevent it from being re-released in theaters in 1956, 1972, 1980, and 1986.

I have never seen Song of the South. Unlike Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, or Mary Poppins, it was never released on video in the U.S. and didn’t play on TV when I was a child. After the theatrical release in 1986, the film was quietly kept in the Disney vault and has never fully resurfaced in the U.S. market.

In 2020, shortly after Disney launched the streaming service Disney+, CEO Bob Iger said the service would never include Song of the South, calling it “not appropriate in today’s world.”

Even without ever having seen the film, though, Song of the South was a part of my childhood. The film served as the inspiration for the iconic Disney ride Splash Mountain. The ride first opened at Disneyland in California in 1989 and was later also added to Walt Disney World in Florida and Tokyo Disneyland in Japan.

Michael Eisner, CEO at the time Splash Mountain opened, was supposedly very involved in its development. Eisner’s background was in film production, and he was also heavily involved in the film business at Disney. I never quite understood how the same man who buried a racist film from ever seeing the light of day after 1986 would green light a project in the theme parks to open in 1989.

I had the opportunity to bring that a version of that question to former Disney Imagineer Tom K. Morris on my podcast in 2020. Morris had worked on some of the initial track layout for Splash Mountain, but was eventually moved off of it and on to other projects.

I asked him whether there were concerns from management about using a film that had been banned from home video release as source material for a theme park ride. Here’s some snippets from his answer:

“There was no direction from the top. It was controversial only in that it was an old film… And it was like, well, why would you pick an old film that's out of date, if you will? It's like, well, what do we have new that we can use?… At that time, there was absolutely nothing. And it also had really good music that was obviously still being used everywhere. And the three Brer characters were still walkarounds in the park. I would say from my standpoint, it was the music that really was driving it…

I was not in the meeting with Eisner on it, but he really liked the idea. You know, if he liked the idea, then we were going to do it. And so I don't remember any controversy. I know that shortly after it was shown to Michael Eisner, it was shown to Michael Jackson, and he loved the idea. And then I moved on to some other projects not long after that, and then wasn't really too much involved.

But my understanding was that they were working with the African-American community on just making sure that we didn't do anything that was weird on it or culturally insensitive.”

As fun as Splash Mountain was, it became harder to enjoy as I grew older because it was rooted in such problematic source material. Even if, as Morris remembers, there were African-American people advising on the portrayal of the characters, the fact that the film was banned still tainted the ride for me.

In 2020, as corporate America was reckoning with race after the killing of George Floyd, Disney announced plans to permanently close Splash Mountain, retheming the attraction to one based on the 2009 film The Princess and the Frog. That film revolved around a young Black girl growing up in New Orleans in the early twentieth century.

At the same time, Disney announced that it would put a greater focus on inclusion in its theme parks. The company went so far as to add Inclusion as a fifth “key” for employees to follow, joining Safety, Courtesy, Show and Efficiency as core operating principles in the parks.

As I’ve written about, my family just returned from an RV trip to Florida and our visit happened to coincide with previews and the opening day for Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, the rethemed version of Splash Mountain.

My smile could not have been bigger riding Tiana’s Bayou Adventure. I spent several months off and on in New Orleans back in 2007 and 2008, covering the rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Katrina for This Old House. I fell in love with the specific music, food, and culture of New Orleans, which is truly unlike anywhere else in the world.

Tiana’s Bayou Adventure manages to be a love letter to the Louisiana bayou, New Orleans cooking, and Crescent City music. It had an authenticity to it that I don’t always expect from theme park attractions.

Perhaps some of that was because of the project team involved. Leading the ride overhaul was a Black woman Charita Carter, executive creative producer. In addition, much of the design team, from composers to costumers to painters were Black, New Orleans residents, or both. They all delivered a ride that exudes passion and heart.

Disney even went so far as to produce an entire soundtrack for the queue of New Orleans standards and The Princess and the Frog remixes and release it on streaming platforms. It’s a remarkably good album (and it even features “Louisiana Fairytale,” the original This Old House theme song!)

With Song of the South no longer present in the theme parks and a beautiful new ride celebrating the Black culture of Louisiana in its place, I also thought it was worth exploring how Disney is doing on their self-proclaimed “Inclusion key” based on my recent visit.

When it comes to inclusion, I see the same problems at Disney that we have in our country at large right now. We often confuse “diversity” with “inclusion” and they are very different ideas. Since Disney is deliberatley striving for inclusion, let’s explore how it differs from diversity.

Diversity means having a multiple points of view represented: races, genders, economic experiences, orientations, religions, places or origin, etc. Diversity is important, but diversity alone does not mean inclusion.

In fact, I would argue that Disney could build 10 more rides featuring people of diverse backgrounds and they still would not have inclusion. Achieving true inclusion is difficult, in both Disney World and America, and this is partially because the foundations of both are so problmeatic.

As I’ve discussed countless times on the podcast, most recently with my new episode with Tracie McMillan, but also with Richard Rothstein, B. Brian Foster and Richard Frishman, Saira Rao, and others, America is built on racist laws and racist practices. This country began with the theft of Indigenous lands and the enslavement of African people and it continues to this day in everything from income inequality to housing access to who gets clean drinking water.

We can elect Barack Obama to the presidency, have Black and Brown figures at the top of entertainment and sports, or have high achieving Black and Brown doctors, lawyers, professors, etc, but that is all just diversity. It’s not inclusion.

Inclusion means that everybody feels welcome, valued, and a part of the greater whole. Inclusion cannot co-exist with racism, misogyny, homophobia, or any other discriminatory system. As such, we can not reach true inclusion in this country until the structural issues that harm Black people and benefit white people are resolved.

To use Disney as an example, Tiana’s Bayou Adventure is a modern masterpiece, but it doesn’t undo the racist structure of the theme park as a whole. Most Disney castle parks are built with several themed lands emanating from the center: Main Street U.S.A., Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland.

Let’s start with Adventureland. Whose perspective is that land told from? Most of the land is told from the vantage point of a white colonizer, often a British one.

Where does the “adventure” of Adventureland take place? It depends on which ride you’re looking at. Explore the Swiss Family Treehouse or see the show The Enchanted Tiki Room and you’re in the Pacific. But at the center of the land is an Aladdin themed flying carpets ride, so that puts the adventure in Arabia. At the edge of Adventureland is Pirates of the Caribbean, set, obviously, in the port of a Caribbean island. The Jungle Cruise sails the Amazon, the Nile, the Mekong, and the Congo. In other words, South America, Africa, and Asia.

Adventureland is not just a land for colonizers, but it’s literally representing the entire non-white world. The point of visiting these places is not to better understand the people who live in these places or the plants, animals, and foods, but rather, it’s to “have an adventure” and gawk at the strangeness of these exotic places.

Frontierland offers the same challenge of being a land told from the perspective of a white colonizer. Frontierland is not the story of the Indigenous people that lived in the American interior for generations. It’s the story of the white settlers who moved west. Though the theme park may not make the genocide of the Native Americans, the decimation of the buffalo population, or the altering of the prairie landscape central to the story for visitors, anyone who knows the history of the frontier is aware of that backdrop.

Even Main Street U.S.A. is a celebration of life in small town America at the turn of the twentieth century. It’s an idealized portrait of a nostalgic time, but it paints over the reality of segregation and sundown towns.

Adding one ride for a Black princess is certainly a step in the right direction towards true inclusion, but it’s not enough.

The reality is that America is a violent country with a racist past that informs our racist present. Just a few days ago, people happily waved signs at the Republican National Convention that read “Mass Deportation Now.”

Until and unless we are willing to deal with our true racist history, any beautiful celebrations of non-white cultures like Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, are simply acts of representation and diversity. They matter, but they do not solve racism, nor do they count as inclusion.

For further listening on this topic, I highly recommend Karina Longworth’s amazing podcast You Must Remember This, which devoted several episodes to Song of the South, Splash Mountain, and racism.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Wow, every bit of this was on time and on point as usual!