Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you like what you’re reading, you can sign up for a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox every Wednesday and Sunday and get my latest podcast episodes:

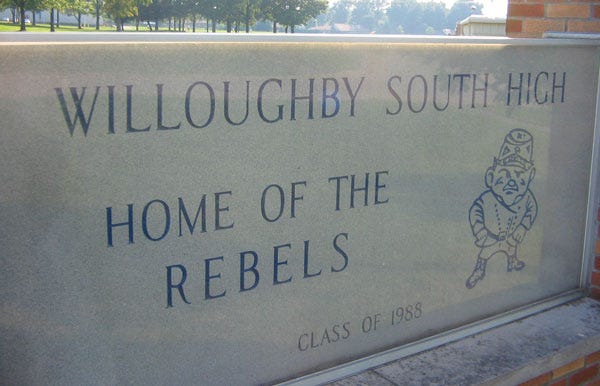

Since rebranding this newsletter to Willoughby Hills earlier this year, I have written several pieces recalling my childhood in Willoughby, Ohio. In many ways, growing up in this suburban small town east of Cleveland was idyllic. But today, I wanted to explore a darker side of Willoughby’s history: its embrace of Confederate symbolism for nearly 70 years, despite fighting for the Union during the Civil War.

This story begins in 1915, when the newly constructed Willoughby Union High School opened its doors to students. The building sat in a prominent location in Downtown Willoughby, not far from a memorial commemorating the local soldiers that died fighting for the Union during the Civil War.

By the late 1950s, the rapid suburbanization of the Cleveland area and the Baby Boom of the post World War II years meant that Willoughby’s population was growing and Union High School was no longer large enough to meet the needs of the community.

So in 1958, Union High School was divided into two separate schools. North High School opened in nearby Eastlake. The school mascot was the Rangers, depicted by a pistol-toting cowboy. This was the era of the western genre of movies and TV shows, so cowboys were certainly in the zeitgeist.

But Willoughby South High decided to take a different approach to their mascot. The splitting of Union High School into North and South was at least rhetorically reminiscent of what had happened during the Civil War nearly a century earlier, when the Union of the United States was divided into North and South.

The decision was made to brand Willoughby South as the Rebels and to lean into Confederate iconography. The Confederate flag was painted on the walls of the school in various places and was regularly flown at sporting events and worn on letter jackets. There was a canon brought onto the field at the football stadium and fired anytime the Rebels scored. The marching band played “Dixie” before every football game, a song whose lyrics include:

“I wish I was in the land of cotton,

Old times they are not forgotten…In Dixie Land I’ll take my stand to live and die in Dixie,

Away, away, away down South in Dixie.”

Growing up, there was always an implied distance between the display of the Confederate flag flown by bigots in the Southern U.S. and the flag of our high school. The general consensus was that our flag was simply a symbol of Willoughby that had nothing to do with the Civil War.

Sam Allard wrote a piece for Cleveland Scene in 2015 that looked at the prevalence of the Confederate flag in Northeast Ohio, with a particular focus on Willoughby South. In his story, Allard quoted from Lisa Stevens, a 1985 graduate of South High and president of the parent group Rebel Families at the time:

"‘I don't think I have ever talked to an alum who doesn't miss it, or at least the days when it wasn't an issue in Willoughby,’ Stevens says. ‘My memories from the '80s include the beautiful flag, not even depicting Southern culture but our 'glory days.'‘"

Sadly, this sentiment isn’t surprising to me as it was pretty commonplace in Willoughby. It was thinking that I myself subscribed to as a teenager going to school there. I think we all recognized that the flag was used by the KKK and Nazi groups in other parts of the country, but we liked to think that our use of the flag was somehow different and wasn’t rooted in hate.

But was Willoughby ever really that innocent?

For generations, the Northeast Ohio region could not have been more different from the Southern states that seceded from the Union. The area where I grew up was designated as an extension of the state of Connecticut known as the Western Reserve in 1662. I remember Yankee styled historic homes that still survive.

According to Case Western Reserve University, the first Black settler to Northeast Ohio came in 1809. As more Black people put down roots in the region, they found a welcoming environment, at least relative to much of the country at that time:

“Throughout most of the 19th century, the social and economic status of African Americans in Cleveland was superior to that in other northern communities. By the late 1840s, the public schools were integrated and segregation in theaters, restaurants, and hotels was infrequent. Interracial violence seldom occurred. Black Clevelanders suffered less occupational discrimination than elsewhere. Although many were forced to work as unskilled laborers or domestic servants, almost one third were skilled workers, and a significant number accumulated substantial wealth.”

Cleveland was a hub for abolitionists prior to the Civil War. As a child, my family used to dine in a tavern that was a waypoint on the stagecoach line between Erie, PA and Cleveland that also served as an Underground Railroad stop.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Black population in Cleveland really began to grow, but opportunities for Black Clevelanders that had been available to prior generations began to disappear. Job opportunities in the manufacturing sector were scarce and segregation began to take hold in public places.

After World War II, changing conditions in Cleveland attracted a fresh wave of Black migration from the South. Unions, in particular the CIO, became integrated and the lucrative manufacturing jobs were suddenly available to Black people too:

“The steady flow of newcomers increased Cleveland's Black population from 85,000 in 1940 to 251,000 in 1960; by the early 1960s, Black people made up over 30% of the city's population. One effect of this population growth was increased political representation.”

Still, Cleveland remained very segregated. Most of the city’s Black population was concentrated on the near East Side of the city. The facilities where different races would interact remained segregated. One of my relatives recalled working at a department store during this era and being uncomfortable with the separate white and “colored” break rooms.

As in many other major cities during this era, the combination of increasing Civil Rights, a federally subsidized Interstate Highway system, and subsidized home loans primarily for white borrowers led to “white flight” from the inner city and an explosion of the suburban population, including in Willoughby, about 20 miles east of Cleveland.

It was against this backdrop, a surging Black population with access to economic opportunities, new settlers in growing white suburbs, and a changing social order that could threaten the economic and political standing of white people, that South High School came into being.

After the Civil War, the Confederate flag’s use died off pretty significantly, even in the Southern states. According to the African American Intellectual History Society, it began to make a resurgence again in the era after World War II, becoming a symbol in all parts of the country against the Civil Rights movement that was gaining momentum:

“Even during the 1960s, when some whites outside the South wanted adamantly to oppose any type of civil rights for black Americans, they used two of the strongest, clearest symbols to communicate their political views and cultural identity: KKK hoods and Confederate flags.”

Even if most people in Willoughby wanted to believe (or at least wanted to say) that South High School’s embrace of Confederate iconography was based solely on a clever joke involving the dividing of Union High School, it’s hard to ignore the reality on the ground in 1958.

In a region that was rapidly diversifying, primarily with Black people migrating from the Deep South, it’s hard to see South High School’s embrace of Confederate iconography as anything other than a racist stand. While neighbors could fly the flag with the cover of supporting the local football team, the reality was that there was suddenly a prominent and potent symbol flying throughout Willoughby’s neighborhoods. It sent an implicit message of who was welcome in Willoughby and who was an outsider.

South High School wasn’t alone in its normalization of this symbol of white supremacy. The Confederate flag started to become a ubiquitous part of American culture in the 1970s and 1980s. When children’s pizza restaurant Chuck E Cheese opened its first location in 1977, the restaurant featured animatronics singing Americana songs as American, California, and Confederate flags waved in time to the music.

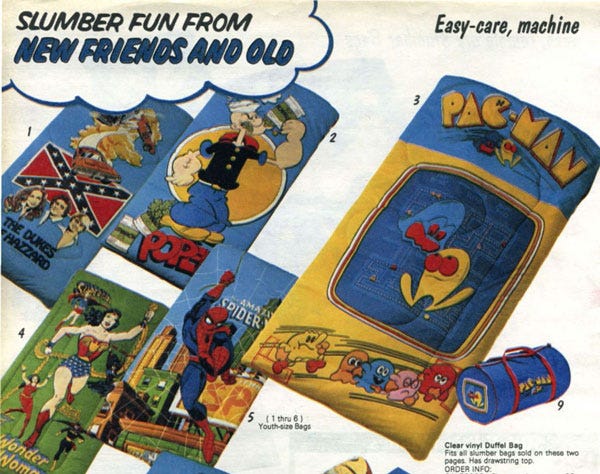

The 1982 Sears Wishbook featured a child’s sleeping bag in a The Dukes of Hazard design with a prominent Confederate flag on the same page as sleeping bags featuring Wonder Woman, Spiderman, Popeye, and Pac-Man.

Walt Disney World opened a new hotel in 1992 known as Dixie Landings that evoked the antebellum South of movies like Gone with the Wind. Some of the themed buildings resembled plantation homes, while another section of the resort was themed to resemble rustic cabins. Even though it was never explicitly stated as such, the juxtaposition of stately mansions with ramshackle shacks certainly resembled master and slave quarters. The resort’s name was changed to Riverside in 2001 and still operates to this day, albeit with less emphasis on the “Old South” theme.

Willoughby South also began to reckon with its mascot and flag during the 1990s. According to Cleveland Scene:

“The flag was removed from the gymnasium and school grounds in 1993 when a visiting basketball team wrote letters expressing dismay and discomfort at the racist symbol. Visiting parents were reportedly shocked.”

Except that’s not entirely true. While the flag may have been removed from prominent areas and was officially banned by the school district at that time, the flag and much of the other Confederate symbolism still survived in other ways.

When I attended South High School in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the flag was still prominently painted on the music room wall, where both the bands and choirs practiced. The marching band still played “Dixie” at every home game and there was a student who dressed as a Confederate soldier mascot at football games.

The flag also was prominently worn on items that came from outside vendors. Letter jackets still featured the flag when I graduated in 2002. Many students chose to have the flag included on their class rings, as Jostens included that option in their catalog. There was a photographer based in Downtown Willoughby who often took senior photos with students laying next to the flag as part of their standard package. I knew kids who had those photos.

Even though the flag was banned, the use of it simply wasn’t enforced in any real way. At the time of the ban, principal Glen Caroff was quoted as saying he wouldn’t prohibit individual students from displaying the flag: "That is an individual freedom-of-speech issue.” I wonder if he also would have considered swastikas as freedom of speech on school grounds as well?

I was raised in an environment where Willoughby’s embrace of the Confederate flag was seen as separate from supporting racism, secessionists, or segregationists. It was a symbol of our high school, our football team, our small town east of Cleveland. Patrick Ward, the principal in 2015, was quoted in Cleveland Scene at the time as saying:

“There is a Willoughby reality, and then another context that our kids don't know,"

But was it really true that people in Willoughby still didn’t understand the context of the flag? I used to believe that was the case, but when I think back on it, I realize that the adults around us understood exactly the potency of that flag and chose to look the other way on it.

The Cleveland area remained racially segregated through my childhood. Most of the time, our football team faced other predominantly white teams from predominantly white suburbs. But there was always one game that we played each year against a predominantly Black team. During that game, the marching band’s pregame show was modified, dropping “Dixie” from the repertoire.

Similarly, the Confederate flag remained painted on the music room wall through my entire tenure at South, despite there being a handful of students of color in the music programs. But there were times when the band director would cover the flag with newspaper and masking tape because of region-wide competitions or recitals being held at the school. It was understood that it was offensive to outsiders that might be visiting, but the flag was revealed again on Monday morning, with no consideration for how it might affect Black and Brown students that saw it every day. Why not just paint over it and be done with it once and for all?

The adults in the room understood the symbolism of the flag and chose to simply paper over it (quite literally), but what about the students? When I was a high schooler, I don’t remember owning an article of clothing with the Confederate flag myself, but I had friends that did.

I didn’t order a letter jacket and chose not to have my class ring inscribed with a Confederate flag, in part because I knew that I liked hanging out in the more racially diverse parts of Cleveland away from my white suburb and was worried it would send the wrong message when I went to those places. In other words, I acknowledged that my classmates, teachers, and administrators were embracing a symbol of hate, even if I wanted to try to see it simply as a symbol of our sports teams.

I moved away from Willoughby after graduating high school, and it has taken me a long time to untangle the embrace of the Confederate flag, both as a symbol of my hometown and as larger symbol of America during my childhood. While I may not have waved the flag myself or worn it on my clothing during those years, I did march to “Dixie” as a band member and certainly minimized any critiques of the school mascot. When I first met my wife, a Brown woman, and showed her my yearbook, she was aghast. Yet I defended the Confederate symbolism at the time, thinking that Willoughby people could somehow divorce our flag from its larger context. I now recognize that it’s impossible to separate the common usage of the flag from our specific usage, in part because South High’s usage seems closely tied to exactly how the flag was being used in the public space in the 1950s and 1960s.

I wish that the adults around me had taken more responsibility for the use of this flag and that South High School had made changes to its mascot and name much sooner. I wish more teachers would have used the 1990s ban of the flag as a teaching moment, giving more context to the meaning of the flag and why it was not appropriate for a public school. Instead, teachers seemed willing to look the other way on the flag, willfully ignoring not only the context of the flag in the outside world, but even more specifically, what it meant in Willoughby and Northeast Ohio history.

I also regret not speaking up more vocally about the flag and mascot in my own time at the school. I used to think that since no students of color complained (at least to my knowledge), it was perfectly okay for us to use the flag. I now recognize that even if Black and Brown people were against the flag, it may not have been safe for them to speak up. As a white male, I was in a position of power to speak up and be heard in a way that they may not have been. I chose silence in that moment, when I should have spoken up to say that all of it was wrong.

It’s worth noting that the debate about the Willoughby South Rebels was also taking place at a time when the Cleveland baseball team was also using an offensive name and mascot. Chief Wahoo, the red-faced caricature of a Native American that represented the Cleveland baseball team, was even more prominent than the Confederate flag in Willoughby.

Cleveland finally changed the name of its baseball team to the Guardians in 2022. Willoughby South, despite constructing a new school building, continues to use Rebels as the team’s name, though it’s unclear whether the Confederate soldier survives as a piece of that.

My takeaway from looking back at the Rebel mascot is that if it barks like a dog, it’s probably a dog. I was raised for most of my childhood to believe that my high school’s embrace of an overtly racist symbol was coincidental, that it meant something else in Willoughby. In looking at the context of the decision to adopt the Confederate flag as a symbol of the school in 1958, it seems quite clear that there was only ever one meaning.

Giving a fresh look to this flag and the meaning it had in my hometown did not happen overnight. It has been a 20 year process of questioning, researching, and thinking. I now recognize that my silence in the face of this racism is just as powerful a symbol as the people who actively flew the flag or posed with it for senior photos. My silence, and the silence of my neighbors, teachers, and friends, allowed this symbol to proliferate and survive.

I may not remember the algebraic formulas or scientific principles that I learned in high school, but I think the most enduring lesson from my time at Willoughby South is that it’s important to speak out against racism, bigotry, homophobia, and any other kind of discrimination. Even if it feels harmless, as in the case of the mascot or name of a sports team, it doesn’t take much digging to realize that the choices of how to name a team are rarely made arbitrarily. For the people with bad intentions, their ideas can only take root when surrounded by complicit silence. When we use our voices to speak out against even small aggressions, it makes the world safer and better for all of us.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

Annie, Woolworth's, and a Racist President

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Wow, this is wild, but thanks for sharing. My mom’s high school in a rural part of NC, but now really considered a joint Raleigh and Durham and Greensboro area suburb, was the Confederates until integration in 1972 and then the Patriots. The imagery and icons shifted, but some of the sentiment remains.

So many of us who are Black kids of promise in these environments were encouraged to explain it away or put our heads down and ignore it on the train to progress. However, progress is really creating the institutions and spaces we need, especially for our children and all youth in our communities.

This is a really thorough grappling with something many of our classmates kinda sorta feel but haven't really done the work to research and articulate.

I, for one, found it particularly helpful in clarifying my own thoughts.

Kudos