Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscribtion to receive emails every Wednesday and Sunday plus podcast episodes every two weeks. There are also paid options, which unlock even more features.

I am a white man. Well, maybe I should put an asterisk at the end of that sentence, because it’s only partially true. But it’s what people assume I am because of my skin tone and I don’t tend to correct them.

A part of this is because regardless of what might show on my 23 and Me, I present as a white man to most of the world and the world treats me as such. I am afforded great privileges simply because people think I’m white.

But anytime I am seen as white and only white, I feel like I am hiding a piece of my identity, that I am not being seen as the full person that I am.

Three of my four grandparents are white, which makes me about 75% white.

But the other 25%, my dad’s father, is Filipino. When we go to family events on my dad’s side, everybody looks brown and there’s traditional American fare served alongside lumpia and pancit. My last name is a Filipino last name, though people assume it’s Italian and sometimes even pronounce it “Ru-chel-luh” (though it’s “Ruh-sell-uh”).

We’re Filipino, but we’re also not fully that either.

My dad’s father (my paternal grandfather) Juan Agor Racela was born in 1898 in the Philippines. At the time of his birth, the Philippines were under Spanish rule, but within months, they would become effectively an American colony as a result of the Spanish-American War (Guam and Puerto Rico were also acquired at the same time).

Filipinos at that time were effectively American subjects rather than American citizens, but they did have access to some American services. My grandfather was able to enlist in the U.S. Navy to ultimately gain passage to the U.S. and become a citizen.

My grandmother was his third wife and he was already quite old when he married her. When my dad was born, it was days before my grandfather’s 56th birthday. My dad and his siblings (he was one of twelve kids) remember my grandfather cooking food and playing card games with his fellow Filipino immigrants in the Cleveland area. Their memories seem more like sketches to me. There’s a photo of my dad and his parents on Christmas morning, but photos from his childhood were minimal.

When my grandfather died in 1967, much of the Filipino culture in our family died with him. It gets upheld in small ways, like in some of the foods served at parties, but part of the reason I struggle with that side of my identity is because I simply have never known much about what it means to be Filipino. I can see myself in the faces of other Filipino and Asian people and feel an instant bond to them when we meet, but I also don’t quite feel like one of them. I’ve never been to the Philippines and don’t speak a word of Tagalog (the official language) or Ilocano (my grandfather’s native tongue).

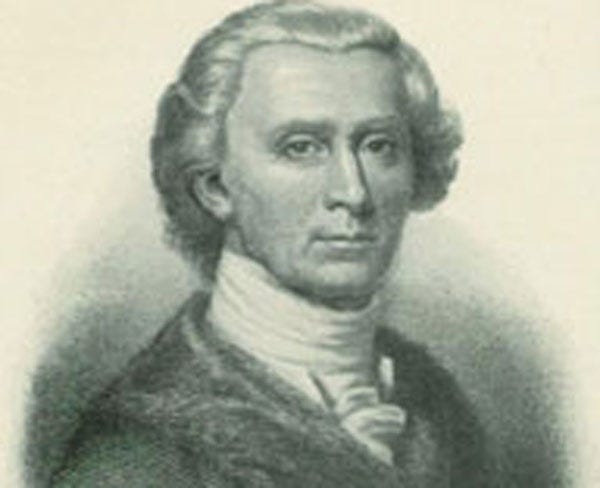

Were it not for my grandfather, I would undeniably be white. My dad’s mom’s side can trace its roots to one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence (Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who was also the first Catholic U.S. Senator). That side of the family can also trace back to slave owners in the more recent past.

For many Americans, having roots dating back to a founding father are worthy of pride. People join The Mayflower Society or other similar groups and proudly discuss their heritage. For my family, Charles Carroll was an interesting trivia fact, but our Filipino roots felt stronger and worth more examination during my childhood and adulthood.

There’s a strangeness in that 25% of Filipino blood for me too. I struggle with imposter syndrome of calling myself Filipino simply because it’s such a small part of me. My kids are only 12.5% Filipino- do they have any claim to identify that way, even though, like me, they will carry a Filipino last name with them through life?

And if my kids are no longer Filipino, what does that mean for the legacy of my grandfather? Does his existence and his marriage to my grandmother simply become a weird little genealogical blip, a speed bump on an otherwise straight path? At least when looking to the future, that becomes the case.

But when looking to the past, it becomes a different story.

We’ve been discussing two generations before me today; my four grandparents. But looking back twelve generations on any family tree yields 2,048 ancestors within that generation and 4,094 cumulative ancestors.

When thought of another way, I may only be 25% Filipino now, but if I look back twelve generations, I have somewhere around 1,000 direct Filipino ancestors! In that context, of course I am Filipino and so are my kids.

At the end of the day, I can’t ignore that this discussion has centered around whiteness, but race is a social construct. To paraphrase Isabel Wilkerson from her book Caste, if you were to line all of the people of the world up from darkest to lightest skin tone, you would be hard pressed to determine where one “race” ends and another begins. Furthermore, you may find many people that are of different races standing next to one another because their skin tones are so similar.

In the context of whiteness, a few generations ago, I wouldn’t have been fully white either. My mom’s side is heavily Irish, which is a group that was discriminated against in the U.S. and has only recently come to be considered “white.”

I suppose the lesson in all of this is that we are all a tapestry made up of the stories of our ancestors: where they came from, who they loved, and where they moved to. These happenstance encounters can come to define us and generations to come in significant ways. Our society wants to fit us all into neat little boxes, but some of those boxes don’t quite hold all of us.

I can trace my roots to the American Revolution, to Ireland, to the Philippines. My skin is white, my last name Filipino, and my kids a glorious mix of cultures (my wife’s parents are Indo-Guyanese and Pakistani).

In short, we are American. At least America on its best days.

Further Reading

I have been reading the amazing book How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr. It’s a great book for understanding the imperial relationship between the continental United States and its outer territories and states including Hawaii, Alaska, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.