Happy Sunday and welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

In case you missed it, I recently renamed Quarantine Creatives to Willoughby Hills. This newsletter will continue to explore topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more, but with a new name.

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscription to have this newsletter lovingly delivered in your inbox twice a week:

I love coffee.

Most people that know me well know that coffee beans are the perfect gift for me because they will always get used. I’ve received coffee as a gift from coworkers, my sister, and just this Christmas, one of my aunts.

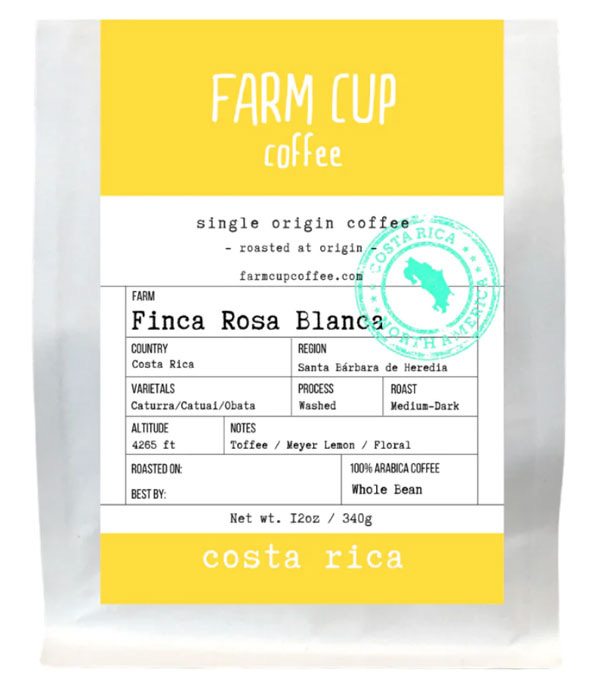

My wife also knows that I like coffee, and for Christmas this year, she decided to surprise me with a very special coffee. Here I am opening the package on Christmas morning, a look of total shock and excitement on my face.

You see, this isn’t just any coffee. It’s a very specific coffee from Costa Rica. This coffee came from Finca Rosa Blanca, an inn and coffee plantation on the outskirts of San José. It’s where my wife and I spent a part of our honeymoon. These beans were imported to the U.S. by Los Angeles based Farm Cup Coffee.

After we opened gifts, I asked my wife why she went to the effort of ordering this coffee that we hadn’t tasted since our honeymoon, almost 13 years prior.

“Well,” she said, “it’s where it all started.”

I suppose our honeymoon could be seen as the start of our marriage, but she further explained that she meant something else. To her, our time in Costa Rica is where our consciousness around food really took root and the experience at Finca Rosa Blanca really set the stage for who we are now.

I’ve written a lot about the way we eat in this newsletter, from exploring the diet we’ve been following for more than a year to discussing what we’ve learned patronizing local farms near us. My wife has also spent the last year sharing recipes specific to our diet (though still tasty for all) on her Instagram and YouTube channels.

She was right to point out that we didn’t become like this overnight; it’s been a slow and gradual process full of learning at each stage. At the time we went to Costa Rica for our honeymoon, our food journey had really just begun.

I had read Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma not long before the trip and was trying to be more conscious about where our food came from, but I was still very much in what I refer to as my “organic Oreo” phase.

I knew enough to know that food grown organically was certified to not contain synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, or pesticides and was seeking more organic options. Yet they often came in the form of highly processed foods that were also high in sugar, like organic cookies. They technically checked the “organic” box, but weren’t exactly health foods either.

Costa Rica was a beautiful country, and as we toured the area around the capital of San José, we fell in love with the views of the coffee fields growing on the hillsides against the backdrop of volcanic hills. These farms looked like the vineyards of Tuscany or Napa, tidy rows of low shrubs producing berries for us to eventually drink.

But not every coffee plantation was breathtakingly scenic. In fact, some of the ones we encountered looked a bit ramshackle, with a mesh netting covering the coffee crops, giving the appearance of asphalt parking lots more than idyllic farms.

We had several models of coffee growing in our mind when we returned to our resort. Little did we know, we were in for an even deeper education.

Finca Rosa Blanca was the perfect place to spend a honeymoon. The hotel was founded in 1985 by the Jampol family. Its mission is to provide comfortable accommodations that are in harmony with the surroundings and which have a light ecological footprint.

Finca Rosa Blanca also operates a coffee plantation, which we toured. It was unlike any of the other coffee fields we passed on the road and opened our eyes to a different way of farming.

Coffee is a shrub that is native to Ethiopia. It has now spread through many parts of Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and some island nations in the Caribbean and Pacific.

Coffee grows best in the latitudes between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn and does well at higher altitudes. Because of this, most of the coffee we drink in the U.S. has to be imported from elsewhere. (There are some coffee farms in Puerto Rico and Hawaii. There is also a boutique coffee farming business in the San Diego area that’s the passion project of singer/songwriter Jason Mraz, but its output is small relative to U.S. coffee consumption).

In its native state, coffee grows on the forest floor, under the canopy of trees, which also means it’s a slow growing plant. The farm at Finca Rosa Blanca took these conditions into consideration when planting, and the coffee they grow hardly looks farmed at all. It was growing under a lush canopy of trees. Touring the coffee farm felt more like hiking in a tropical rainforest than trudging through a muddy farm field.

The trees shaded the coffee plants, but they also convert nitrogen gas in the atmosphere into a form of nitrogen that can be absorbed through coffee roots. This is a process called nitrogen fixing and it reduces the need to apply fertilizers. The trees also had deeper roots than the coffee, which helped control soil erosion.

Remember, much of Costa Rica is tropical rain forest, so by preserving some of the natural trees and other plants, an entire ecosystem was able to be maintained, with a farm growing around it. The forest was alive with migratory birds, pollinating insects, and the like.

Growing amongst the coffee plants were other food crops as well. I remember seeing citrus, pineapples and bananas. Our guide explained to us that the banana plants had a symbiotic relationship with the coffee. When it would rain, the bananas could soak up extra water and hold it like a sponge. Banana leaves then drip out excess water, which can help irrigate coffee plants without needing an elaborate irrigation system.

Here at Finca Rosa Blanca it seemed that indeed you could have it all. An existing ecosystem could continue to exist and even thrive with human intervention. A combination of native and non-native plants could be planted to create something approximating the natural order while still yielding productive crops.

The coffee at Finca Rosa Blanca was also grown organically, meaning no synthetic chemicals like pesticides or herbicides were used.

It can take more work to grow in harmony with nature like this, and it required a pretty broad understanding of the needs of lots of things: the natural foliage, the farmed crops, and the wildlife in the area.

The other coffee farms we had passed earlier in the trip were following a different model of production, one that attempts to maximize yield and profit above all else. These systems do come with great costs, but because those costs do not directly affect the bottom line of the business, they are harder to calculate.

Clearing the natural rain forest away to plant coffee crops allowed for tighter spacing of plants, and thus higher yields, but it also had a ripple effect. By removing the forest, a natural habitat for birds, lizards, and other animals was also gone. This reduces the predators that prey on coffee-loving insects. In an open field with no predators, the insects run rampant and farmers must resort to spraying pesticides on their crops.

There is also no natural source of fertilizer, like fallen leaves that decay and turn to compost, so synthetic fertilizer needs to be sprayed. According to Equal Exchange, a coffee co-op:

“Conventional coffee is among the most heavily chemically treated foods in the world. It is steeped in synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides…”

The varieties growing in the open sun were hybrids bred to be sun-tolerant, even though coffee naturally grows in the shade. The coffee fields covered with mesh tarps were an attempt to shade the coffee plants from the sun to give them some of their natural growing conditions, while still utilizing the dense row method that the other farms use.

When my wife referred to Finca Rosa Blanca as “the beginning” I think visiting there really was the first time I had an awareness that farming came with choices. There was a conventionally accepted way of doing business that evolved because of pressure for higher yields and bigger profits. Most farmers subscribed to this method, likely because it was how they had been taught. Many may not realize there’s an alternative.

But thankfully, there were some farmers, like the team at Finca Rosa Blanca, that found a better way to do things. Some of their methods were rooted in deep tradition, observation, the latest science, and a bit of common sense.

If farmers have choices in how they grow, that means we as shoppers have a choice in how we consume too. Once we know that there are better options, I think it’s incumbent upon us to seek out those choices whenever possible.

In the case of coffee, there are a few different certifications to consider:

Rainforest Alliance Seal: In order to earn this seal, a farmer must follow certain sustainability requirements that protect forests, climate, human rights, and livelihoods.

Certified Organic: In order for a product to carry the organic label in the U.S., it has to be certified to be non-GMO and grown without synthetic chemicals. The organic label does not mean that the coffee was grown in the shade or in a natural setting though.

Bird Friendly: A label developed by Smithsonian for coffee and cocoa that conserve habitat and protect songbirds.

Single Origin: Most coffee is made of a blend of beans, but some coffee roasters and coffee shops offer beans from a single plantation. The baristas in the shops can often tell you more about the specific growing conditions of the coffee and answer questions about the origin.

After learning more about how coffee grows, I have been more conscious about the coffee I drink. Whenever possible, I try to brew my own coffee at home. This allows me to know the origin, but it also prevents the waste that comes with ordering coffee on the go in disposable cups and lids.

Since I am on the go a lot, I invested in a travel mug that had a built-in French press a few years ago. I can add coffee grounds and hot water to the mug and have a fresh cup of coffee without having to fuss with coffee makers or filters.

Of course, all the best growing practices in the world are meaningless if the coffee in question doesn’t taste great. I still think about the advice that our tour guide gave us at Finca Rosa Blanca on how to select the best coffee as a pantry staple. He advised that we brew the coffee hot and black (no cream or sugar), then let it sit out at room temperature. Often, the heat can mask the flavors, but drinking a cool cup of coffee allows the full flavor profile to come through. If a coffee doesn’t taste great when cool, it probably shouldn’t be your first choice when it’s warm either.

It’s been almost 13 years since our honeymoon in Costa Rica but the memory of seeing coffee growing in many different ways really did change how I look at the food that I consume.

Your Turn!

Tell me more about how you take your coffee and if you ever pay attention to where it comes from. Please drop a comment below!

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

If you enjoyed this issue, please share forward it to a friend or share it on social media:

Stay Safe!

Heath