Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

It’s so easy to feel invisible these days.

I walked into a public restroom recently with four or five motion activated sinks. I waved my hand and the water didn’t turn on. I tried the next one and nothing. On the third try, I finally got some water. The machine eyes of these faucets didn’t see my humanity.

We walk down the street and rather than look at each other, we stare into our phone screens. We keep AirPods in our ears so we don’t have to hear each other. Technology should be making us closer, increasing our empathy, connecting us across geography, politics, or language. Instead, it makes those closest to us, those right across from us, those breathing the same air in a crowded elevator, distant.

Our social media feeds no longer show us what our friends are doing. We now watch videos from strangers that we don’t follow. Comedy sketches, dance moves, health tips, conspiracy theories. All delivered in a few seconds. Then on to the next one.

It wasn’t that long ago that a newspaper was printed in logical sections. Here’s the local news, the national news, business, sports, entertainment. We could scan sections, we could skip sections, we could dive deep. But we knew where we were and where we were going.

Now, our attention is being tested and tried in a split second. Keep scrolling. What’s this? Scroll up. Scroll down. Swipe left. Swipe right. Double click. Repeat. Sports. Diets. Politics. Plane crash. Buy this. Consume. Consume. Consume. Keep scrolling.

We can no longer process. We can no longer think at this pace. We have thousands of followers in this virtual world. But technology is making us all invisible.

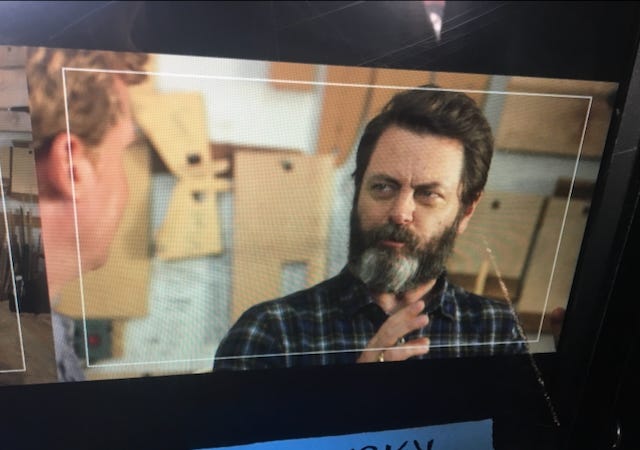

In 2016, I was fortunate enough to film a tour of Nick Offerman’s wood shop in Los Angeles for Ask This Old House. We spent a leisurely morning in the shop, surrounded by antique drill presses, large slabs of wood, and even a piano. In all, we were probably on site for three or four hours, so we had some time to get to know Nick and he had some time to chat with our crew.

At one point when there was a break in filming about half way through the morning, Nick began looking around the room and pointing. “Heath… Jay… Kevin… Sarah… David…”

He was partially speaking to all of us, partially testing himself. We had all shaken hands at the beginning of the day, but Nick was now checking to make sure that he had remembered everybody’s name.

It was a small gesture, but one that still sticks with me nearly a decade later.

As a producer and director, I am used to being seen more for my job role than as an individual. Actors, camera operators, stage crew, interview subjects, and many others look to me for guidance, direction, and focus on a set. But I’m still often seen more as “director” than as “Heath,” in the same way that somebody else might be seen as “barista,” “cashier,” “dentist,” or “nurse” rather than as “Darla” or “Maureen.”

I’ve run into Nick a few times since that first meeting at his shop, interviewing him for This Old House, meeting him backstage at his comedy shows, or having him as a guest on the podcast. Every time, he recognizes me, knows my name, and speaks to me. I felt seen, not just as a producer, but as a person.

As I discussed in my podcast episode with Ben Napier, my family and I recently moved to Western Massachusetts so that we could join a Waldorf school. I’ve written some about Waldorf philosophy in the past. It’s a beautiful curriculum that incorporates a lot of classical arts like music, painting, and movement along with practical arts like woodworking, knitting, and farming.

Perhaps what I value most about our Waldorf community though is how intentionally everybody in the community chooses to see each other.

It starts with the teacher, who greets each child at the classroom door every single day with a handshake or a hug and a personalized welcome. The teacher sees each student as an individual with a name, with a story.

That attitude extends to everybody in the community, including parents.

At other schools we’ve attended, I was always known as my child’s dad. I doubt that most of my kids’ peers at our old schools knew my name. If they had ever even heard it, they didn’t remember it, or didn’t call me by my name.

In my first weeks at this new school, I accompanied my daughter’s class on an overnight camping trip to Cape Cod. On that trip, I was not my daughter’s dad. I was Heath. Kids addressed me that way. They came up to me and just started talking.

As I’ve met parents in my both son and daughter’s classes, I’ve noticed a strange thing. We are meeting as people, as individuals. Sure, I know which kids belongs to each parent, but that’s not the sole focus of our interactions. I feel like I’ve gotten to know these parents for who they are, and they’ve gotten to know me for me, not just as my kids’ dad.

We recently spent two weekends camping at a farm in New Hampshire with our kids’ classes (my son’s class went one weekend, and my daughter’s went three weeks later). After both trips, I felt good. I felt renewed. I felt seen.

I worked with the other parents towards common goals. We cooked communal meals together in the large kitchen. We sang songs around the wood stove as a group. We hiked through the woods in deep snow. At night once the kids were asleep, the parents would gather in the dining room to play games and share drinks.

My son’s teacher brought her husband and two small kids on the trip with her. We didn’t just see her as a teacher, we saw her as a wife and a mother. My daughter’s teacher brought her partner along and we got to know him.

Nobody was seen only for their relation to one another, but was also seen for their individuality, for their humanity.

This is not just an anomaly of this particular school, but a core tenet of Waldorf education. It focuses simultaneously on both the individual and that individual’s role within the community.

Here’s how Marjorie Spock, a prominent environmentalist and Waldorf educator, described the Waldorf approach in a 1947 essay:

“In all such experience the group rather than the individual is paramount. In eurythmy, for example, the emphasis is upon patterns of movement. In recitation the speaking is choric. In music all participate in every song and instrumental composition. Individuals may have their single parts to perform, as in a drama, but these must have relation to the whole. Such communal experiences of creating beauty are freely and joyfully engaged in, and they are in their very nature prototypes of the highest conceivable form of free, creative social relationships…

The child whose education has thus built up in him a profound respect for human beings, which has fostered his creative powers and enabled him to drink deep of the joy of group creating, will be person and artist enough to desire, envision, and help bring into being truly healthy forms of society.”

Perhaps somewhat ironically, the focus on group cohesion over individual impulses actually results in the individual feeling more seen and being allowed to develop more fully.

As I’ve been going about my days lately, I’ve been thinking about the importance of learning names, of meeting people, and of building community so that we can all work towards our common goals. The rugged individualism and isolationism of American society isn’t working, and technology continues to separate us even further.

The antidote? Connecting with each other and building real, deep, true community where everybody is seen. That may sound like an overwhelming task, but it really starts with the simple act of shaking hands and learning names. From there, community grows and flourishes. And we are all less invisible.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

This topic is SO important to explore. Critical even. I have observed the same human disconnect as the technology we use, and instant access to all manner of info/entertainment, has become more integrated into our every waking hour. The true human experience is falling right through our fingertips more every day, but we are too distracted with the near impossible to fight, instant gratification, digital circus surrounding us. Lets hope there is some natural yearning to ween off the phones, computers and "social media" in the years to come. I still have a ton of faith in humanity that a more intelligent and fruitful way of existence will slowly come back around. Using technology in a more prudent and responsible way to solve problems and create abundance, as opposed to IT controlling our minds, emotions and valuable time. Thank you Heath! As always, another fantastic post!