Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you enjoy what you’re reading, please consider a free subscribtion to receive emails every Wednesday and Sunday plus podcast episodes every two weeks. There are also paid options, which unlock even more features.

On a recent episode of my podcast, a guest made an observation that has lingered in my mind for weeks and it has reframed how I view the world around me.

The interview was with Richard Frishman and B. Brian Foster about their amazing book Ghosts of Segregation.

Frishman is a white photographer who was describing to me how he used to love to capture scenes of Americana. After the 2016 election, he felt an urgency to refocus on scenes of greater social importance. This led him to start photographing locations that illustrate America’s racist past and present.

Foster, a Black professor and author who wrote several essays about race for the book, then clarified that he didn’t think that Frishman’s love of Americana and his photos depicting racism were two distinct ideas that can be separated. According to Foster during the podcast:

“My position is that the historical record suggests that racism is Americana. Mundane and everyday and taken for granted and sometimes, oftentimes invisible, certainly for folks who are in privileged and empowered positions.”

Racism is Americana.

It was such a simple idea and one that seemed so obvious. But as a white male myself, it was also one that hadn’t really occurred to me. Or at least I hadn’t thought about it in such a succinct way before.

Three simple words that say so much: Racism is Americana.

The more that I look back on my own travels around this country, I can’t help but agree with Brian and I am embarrassed that I somehow missed something that was right in front of me for all of these years.

Of course, there were some various obviously racist establishments that once lined American roadways.

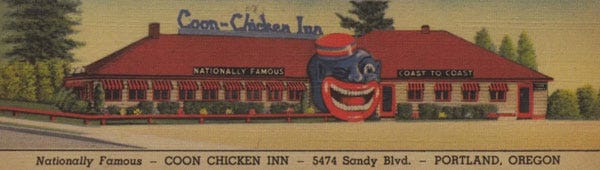

In Friday’s newsletter, I mentioned that I’m reading an old book about roadside restaurants from 1986 called Orange Roofs, Golden Arches by Philip Langdon. In the book, one of the popular restaurant chains Langdon mentions was known as Coon Chicken Inn. Here’s how he describes it:

“Eccentric buildings are often remembered fondly now. What is forgotten is that scattered among the visual jokes were a few buildings that took their supposed humor from unattractive stereotypes. In 1924 the small chain of Coon Chicken Inns was founded, and by 1934 there were inns in Salt Lake City, in Portland, Oregon and on the outskirts of Seattle. These restaurants, specializing in Southern fried chicken, were unexceptional log-walled buildings, notable only for a visual gimmick: on the front of each was a face- at least 10 feet high —of a black bellhop or waiter, one eye closed in a perpetual wink while his mouth gaped open in a monstrous grin. At the Coon Chicken Inn in Salt Lake City, customers walked through the mouth to enter the restaurant, where they were served by black waiters. The theme was reinforced by presenting the same black stereotype on menus and dinner plates.”

Yikes.

More popular than Coon Chicken was Sambo’s, a chain that once boosted around 1,000 locations nationwide. The business name was supposedly a portmanteau of the two founder’s names: Sam Battistone Sr. and Newell Bohnett. However, the name Sambo also had other meanings, as PBS SoCal described:

“By 1957, the name Sambo already had a long and controversial history. Since as far back as the 1500s, the name had been used to denote a black man. By the 19th century, “Sambo” had become an archetypal degrading character in literature and minstrel shows. “Sambo, the typical plantation slave, was docile but irresponsible, loyal but lazy, humble but chronically given to lying and stealing,” historian Stanley Elkins wrote. “His behavior was full of infantile silliness and his talk inflated with childish exaggeration.” Education specialist Jessie Birtha explained that “the end man in the minstrel show, the stupid one who was the butt of all the jokes, was Sambo.”

Even if the name Sambo was coincidental, the restaurant chain decided to lean into the association with the book Little Black Sambo, depicting a Sambo boy with a tiger in their restaurants, menus, and more.

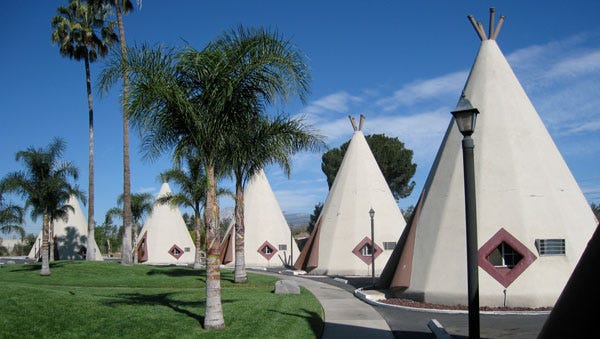

Equally as present along Roadside America is a stereotyped and caricatured view of Native Americans.

In looking back at old photos from my road trips over the years, I found a lot of appropriated Native imagery and symbols, from depicting costumes to motels built to resemble tipis, like the Wigwam Motels in Arizona and California.

In the case of both Black stereotypes and Native American stereotypes, these depictions were fairly common outside of roadside buildings at the time. Brands like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben’s depicted similar tropes. Countless schools across the country still to this day have “Warrior” football teams (including my own middle school). Cleveland fans rooted for the “Indians” until 2022. Atlanta fans still cheer on the “Braves.”

These stereotypes and caricatures are overtly racist, but there’s also a different breed of racism that was even more common along American highways.

For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by Route 66, the highway that at one time connected Chicago to Los Angeles. The road first entered popular culture in John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath as the path of migration for those fleeing Oklahoma for California during the Dust Bowl.

Route 66 is partially known for its motels, restaurants, and other roadside attractions with flashy neon signs or eye-catching architecture, but it didn’t look that much different from other roads in America during the 1940s and 1950s. U.S. 1 along the East Coast from Maine to Florida, the east to west Lincoln Highway, and many other similar roads were also littered with neon and tourist traps.

But Route 66 somehow lodged differently in the American consciousness, perhaps because it even had its own theme song.

“Get Your Kicks on Route 66” was written in 1946 by Bobby Troup, a white man who took inspiration from his own trip west to California. The song was first recorded by Nat King Cole, a Black man. Yet had Cole travelled the Mother Road, his experience would not have been the same as Troup’s.

According to Frishman and Foster in Ghosts of Segregation:

“Along the 2,448-mile length of Route 66, less than six percent of restaurants and hotels welcomed African American people. Black motorists on Route 66 in 1955 didn’t have overnight lodging options from the Texas border to Albuquerque, a distance of 215 miles, unless they were lucky enough to find a room at one of three small Black-owned Tucumcari boarding houses far off the highway.”

This, of course, was not unusual. Because of segregation and prejudice, Black motorists were often not permitted to visit the same roadside businesses as white travelers. The Negro Motorist Green Book was published by Victor H. Green and it flagged Black-owned and Black-friendly businesses for travelers.

I knew of the Green Book, and I knew about Jim Crow and segregation, but for some reason, it had never occurred to me that this prejudice existed outside of the Deep South, and certainly not on Route 66.

I have traveled long stretches of the road through California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Illinois over several years. I have taken hundreds of photos of the roadside attractions and neon signs. I imagined what these small towns looked like in their heyday before being bypassed by the interstate. Never once did it occur to me that the Route 66 I was romanticizing, indeed a large proportion of the roadside restaurants, drive-ins, hotels, motels, and other attractions all across the United States, were only available to some travelers, not to all.

This has been a quick survey, rooted in my own travel experiences, and it has barely scratched the surface.

Whether by mocking travelers of color through offensive stereotypes or excluding them from doing business at all, the clear truth is that B. Brian Foster was 100% correct when he says that “Racism is Americana.”

Now that I’ve seen the truth, it’s hard to look at those neon signs in quite the same way.

Thanks for reading Willoughby Hills! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Related Reading

Pay What You Call For and Drink What You Please

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

Wow. So appreciate this. And I need to listen to this episode of your podcast!

Once again, Heath, you unpack some seriously complex issues and distill them into understandable form. Thank you for continuing the conversation. Best, Rich