Pay What You Call For and Drink What You Please

400 Years of American Roadside Signage, from painted wood to flashy neon

Welcome to another edition of Willoughby Hills!

This newsletter explores topics like history, culture, work, urbanism, transportation, travel, agriculture, self-sufficiency, and more.

If you like what you’re reading, you can sign up for a free subscription to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox every Wednesday and Sunday and get my latest podcast episodes:

Imagine this: you’ve been traveling all day and are beginning to grow weary. The sun will be setting soon. You’re hungry and need a place to spend the night. Suddenly, at some distance down the road, you spot a large sign which promises food and lodging. Relieved, you decide to take a break and rest for the evening.

When do you think the scenario I just described took place? It could have been in the 1920s, the 1950s, or even yesterday. But it wasn’t. The scene I’m describing started happening on this continent in the mid 1600s, before the United States was even a country.

I recently wrote about attending Old Sturbridge Village’s Maple Days event. On that visit, I stopped in the gift shop and my eye was immediately drawn to a small book by Jack Larkin titled The New England Country Tavern (it’s selling for a lot on Amazon, but was only $6 in the gift shop).

That book ended up lighting a spark in me that led me to investigate roadside signage at a deep level.

The Colonial Tavern

In Colonial New England, and continuing into the mid-1800s, taverns were the main place where locals and travelers could meet and mingle. In an era before restaurants, the tavern was a place to grab a drink, play some cards, and catch up on the local gossip. The Buckman Tavern in Lexington, MA was where local militia members plotted against the British prior to the Revolutionary War.

For travelers, mostly on horseback or riding in stagecoaches, taverns functioned like a highway exit does in our modern era. They were a place for stagecoach drivers and passengers to grab a bite to eat and then take a rest. Horses could also be stabled at the tavern or even swapped out for other horses, the old fashioned equivalent of a gas station.

The accommodations were sparse by today’s standards. Travelers were expected to share a bed with other same-sex guests (except married couples, who slept together). There were often multiple beds per room. It may not have been luxurious, but these taverns sufficed for a quick overnight stay.

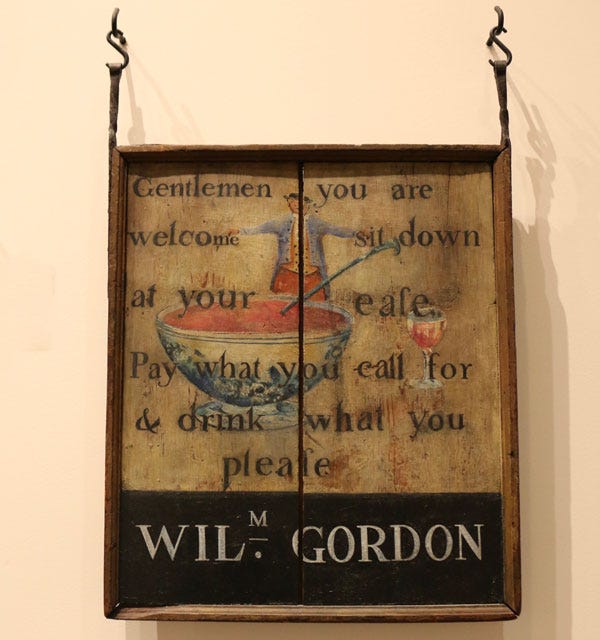

One feature that every old tavern had in common was a large sign, meant to attract the attention of passersby. According to Larkin:

“Tavern signs were a widespread and distinctive feature of the New England landscape. Since 1647 they had been required by law, when Massachusetts decreed that every establishment ‘shall have some inoffensive sign, obvious, for the direction of strangers’ posted within three months of its licensing.

Signs customarily stood near the tavern's entrance or directly across the road from it and served to attract the attention of travelers and let them know where beds, food, drink, and animal fodder could be obtained. Local taverngoers, of course, did not need a sign to find the tavern; outside the cities, few purely local establishments such as craftsmen's shops and stores ever used them. Landscape paintings and drawings, and a few very early photographs, tell us that early and mid-nineteenth-century signs were of imposing height, so that they could be seen easily from a distance and read from horseback or the driver's seat of a stagecoach.”

One of the reasons that old taverns needed signage was that they were built very similarly to the Colonial homes of the era. In other words, there was no way to distinguish a private home from a “publick house” were it not for the signs.

The signs could be quite complex. They were almost always made of wood and could be painted with elaborate designs. They were also huge!

I didn’t quite grasp the scale until a recent visit to the Connecticut Historical Society Museum and Library in Hartford. The museum has more than 60 original tavern signs from around New England on display and they were very impressive in real life!

The signs all include the proprietor’s name. Some of them have elaborate descriptions of the services on offer inside.

But many taverns featured nothing more than a simple design showing the tavern features. They were easy to understand at a distance and didn’t require reading for the illiterate traveler. An image of a wine bottle and goblets told the whole story.

From Horseback to Iron Horse

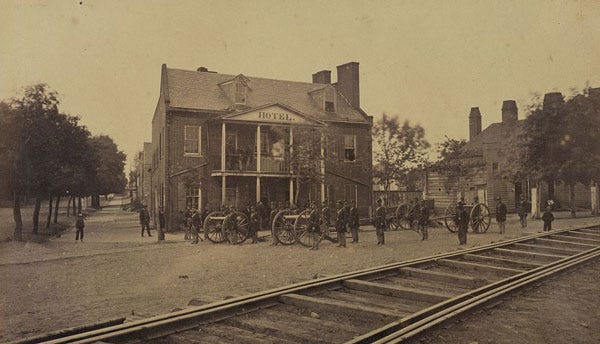

By the mid 1800s, country taverns began to disappear because of a change in how we traveled. The railroad allowed passengers to get around the country must faster and more efficiently. Rather than stop off in quiet country towns along the main road, railroad travelers tended to stop in larger cities. Newer railroad hotels catered to these travelers with the latest amenities.

Boston boasts the oldest continually operating hotel in the United States, the Omni Parker House. It began operation in 1855, relatively young by New England standards, which gives you a sense of just how new the idea of a luxury hotel is.

In large cities and smaller towns with railroad access, hotels grew in size and opulence as the fortunes of the United States as a whole was on the rise in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Camping Out

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Americans once again saw a shift in how they traveled, adopting the automobile as a new means for mobility. Cars suddenly brought traffic back to the old country roads and stagecoach routes, but most of the old country taverns were gone by that point.

Driving in the early days was a dusty affair. Travelers that needed a place to rest for the night would find that fancy railroad hotels may be the only available accommodation, yet sweaty, dirty drivers didn’t exactly fit in with the more genteel crowd in nicer hotels.

But cars came with an advantage that railroads didn’t- they could pull over at the side of any road to rest. Drivers began to pack canvas tents that they would pitch in empty fields, cooking dinner over a small campfire and spending the night anywhere they could find a flat site.

Farmers and other land owners grew frustrated with motorists camping on their property and leaving behind litter, while enterprising Main Street merchants saw an opportunity to do business with these new travelers. After all, the people that could afford a car and a vacation in the early twentieth century were wealthier and had more disposable income- why not have them spend their money in town?

To combat camping on private land and bolster local businesses, cities began to build municipal campgrounds, sometimes in a park or other vacant land where patrons could walk to Main Street and shop or dine. These campgrounds were often little more than a place to pitch a tent, but camping was offered free to motorists to entice them to spend money in town.

These campgrounds became a source of civic pride too, as Chester H. Liebs describes in his book Main Street to Miracle Mile, which chronicles the development of roadside America:

“Competition heated up between neighboring towns as each strived to build the most popular motor camp. Communities added scores of extra conveniences including picnic tables, fireplaces, flush toilets, showers, sheltered eating and recreation areas, even electrical hookups and then proclaimed these inducements on signs placed along roads leading into town. By 1922 the U.S. Chamber of Commerce estimated that more than one thousand of these town commons for transient travelers had been built from coast to coast.”

The era of municipal campgrounds was short lived. As cars became more affordable and ubiquitous, suddenly it wasn’t just wealthy people that could afford to travel by car and community leaders feared that their campgrounds might attract unsavory people.

To combat this, cities began to charge a lodging fee. The hope was that this would clean up the municipal campgrounds, but once motorists were asked to pay for camping, it gave rise to private campgrounds. These could be as simple as a farmer offering a place for a few campers to pitch a tent to more elaborate campgrounds which featured abundant amenities.

With an explosion in private campgrounds by the late 1920s, operators were looking for ways to attract patrons to their site. Savvy business owners realized that people would pay a premium to sleep in something more permanent than a canvas tent, and they began to build primitive roadside cabins that could be rented to travelers.

Again quoting from Liebs:

“First-generation campground cabins were usually rudimentary affairs- wooden enclosures with screened openings, often without furniture. Campers usually supplied their own bedding.”

These roadside cabins made their way into popular culture too. The classic 1934 Frank Capra film It Happened One Night is one of the early road trip movies and features a scene where Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, two unmarried travelers (and rivals in the film), are forced to share a cabin.

These cabins were a hit with travelers and the next generation were a major step up from a campsite, according to Liebs:

“By the early 1930s, the amenities contained within the four walls of the motor-court cabin represented considerable advance in comfort over the bare-bones appointments of the cabin camp of a few years before. Crude bunks and Spartan furnishings gave way to more commodious accommodations. Real beds, dressers, desks, rugs, lamps, pictures- even if castaways from the owner's house or purchased secondhand- helped make cabins feel less like camp and more like a guest's own bedroom… by the mid-1930s the transition from a place to camp out to home-away-from-home was virtually complete.”

From Cabins to Motels

The next evolution in roadside accommodations is the birth of the motel, which happened in earnest after World War II. A motel is essentially a row of roadside cabins condensed under a single roof. This saved the construction costs of running plumbing and electricity to several small buildings.

Traveling in the late 1940s and early 1950s was very different than it is today. The first idea of a standardized motel experience, happened in 1939 when seven independent motel owners in Florida formed Quality Courts. Holiday Inn didn’t begin operation until 1951, with Howard Johnson’s offering lodging in 1954. Prior to this, motels were mom and pop operations, locally owned one-offs.

The roadways were different then too. The laws that established the Interstate Highway system began to be passed in 1954, but before that, a road trip often meant driving on state highways or smaller local roads. These roads went directly past local businesses.

Just like the tavern owners in the 1600s, motel proprietors turned to signage to attract passing travelers. While a 6 foot painted wood sign may have garnered attention from a Colonial era stagecoach, something more eye catching was required to compete with the faster speeds of the car.

It turns out that the neon sign was the perfect fit for advertising motels, restaurants, and other roadside businesses. The technology of making glowing signs was first developed in France in the early 1900s. It began to make its way to the American roadside by the 1920s and really exploded by the midcentury.

Like early tavern signage, neon signs often used a combination of striking imagery and text to either show the purpose of a business or to attract attention. I’ve always been struck by the beauty of neon and have spent many vacations snapping photos of roadside neon.

Of course, the neon era didn’t last forever. Interstates began to stitch together more of the country. Travel became faster, but also somewhat more monotonous. The controlled access of an interstate meant that lodging, restaurants, and gas stations were all clumped together around exits. National chains like Holiday Inn and McDonald’s began to spread to every corner of the U.S.

As shown in films like Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 thriller Psycho, the mom and pop operators of small motels often found the main highway where they set up shop a generation earlier was bypassed by the interstate, slowing steady daily traffic to a trickle. (And yes, my takeaway from Psycho was the change in our built environment.)

As the luster of the local roadside began to crumble, laws began to be passed around the country that outlawed neon signs or restricted how they could be constructed, citing them as gaudy. It’s a bit ironic to imagine Colonial governments in the early days of European settlement on this continent mandating that tavern owners display a sign by law, and then a few centuries later, outlawing some forms of signage that was essentially serving the same purpose.

Neon Glows Again

With so few neon signs surviving, the ones that are left are no longer seen as blights but are often targeted for preservation. U.S. Route 1 was once the main thoroughfare from Maine to Key West, and the road was littered with neon in its heyday.

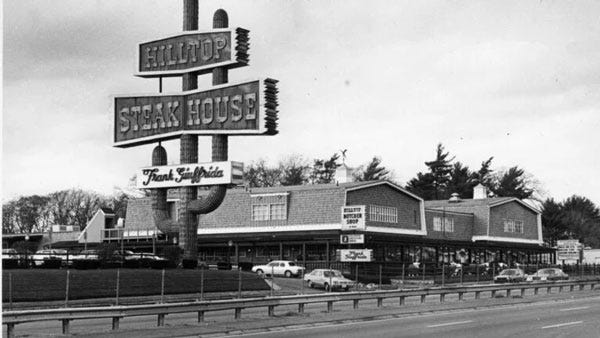

Saugus, MA was once the home to Hilltop Steak House, a 1,400 seat restaurant and butcher shop that opened in 1961 and was apparently once considered the busiest and most profitable restaurant in the country. The restaurant was recognizable from a distance by its 68 foot tall neon green cactus sign.

Hilltop closed in 2013. The restaurant and massive parking lot were demolished, replaced by a mixed use development of apartments, shops, and restaurants. Building at a higher density along a major roadway with access to Boston made more sense in modern times than simply housing a sprawling restaurant. (I’ve written about how a similar change may be underway at Kowloon on the other side of Route 1).

But the neon sign at Hilltop lives on and has been retrofitted to showcase the current businesses that occupy the space, while also nodding to the past.

It’s unclear what the next chapter in American roadside lodging and dining holds. In looking at this topic a little deeper, I’ve learned that history really does repeat itself and the starting point of a story is often much further back than we might believe initially. I would have never connected neon motel signage to a painted wooden tavern sign, but it turns out that they have quite a lot in common.

A Special Bonus!

Thank you for reading! This piece took more than a month of research and included several field trips.

If you’re interested in seeing even more photos of historic signs, from antique tavern signs to midcentury neon, I’ve created a bonus post for paying members that includes more than 25 additional photos from my travels around the country over the last 15+ years.

If you’re not yet a member of Willoughby Hills, you can upgrade your subscription today to get early access to podcast episodes, regular bonus video posts, and supplemental bonus posts like this photo gallery.

Related Reading

If you’ve missed past issues of this newsletter, they are available to read here.

What a gift to start off my Sunday morning with this latest issue of Willoughby Hills! Thank you! Happy Easter to you and your family brother.

I have always loved signs of all kind. I still giggle when I see “EAT GAS” wording on signs. btw. I like billboards..I know all the reasons against them, however I still like them. I am glad that I am old and fun things were along highways etc.